The Peace of the Pākehā Is More To Be Dreaded Than His War

In these posts, I tell of two of my ancestors who, in 1861, arrived in Aotearoa New Zealand. My Irish great-great-grandmother Maria Dillon landed in January, just a few months before the gold rush that would utterly transform Dunedin and the province of Otago. My great-grandfather, the Scotsman Archie Sligo, was among the flood of hopeful diggers who disembarked in October of that year.

I wanted to learn more about the forces that propelled them from their homelands, what attracted them to their new country, what happened here shortly before they arrived, and what they encountered as they set about making new lives for themselves.

These posts reveal part of their stories.

Previously: Muskets Became an Ill-fated Necessity as the People Prepared to Defend Themselves Against Northern Aggression.

As reported in a previous post, by the late 1830s the British government had reluctantly decided to acquire New Zealand as a colony. It was responding to the suggestion that the French might proclaim its authority over the country and to pressure from British missionaries that London needed to control lawless and dissolute Europeans who were setting out to cheat and corrupt Māori society, including through unethical land purchases.

A similar impetus towards colonisation also came from the strong humanitarian movement in the UK. The English version of the Treaty was assumed to establish British sovereignty over its newest colony, but Māori chiefs signing it appeared clear in their minds that the Treaty assured them that they would retain control of their land. By then, relationships between Māori and Pākehā had been developing for a generation, and around half the indigenous population, seeing the value to be gained from acquiring literacy, participated in the services provided by the mission schools and churches.[1]

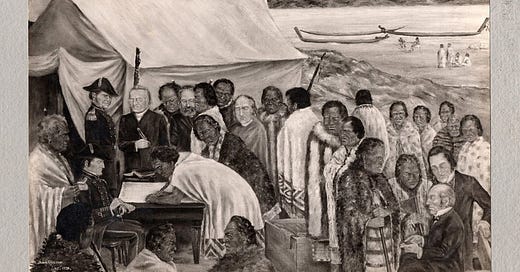

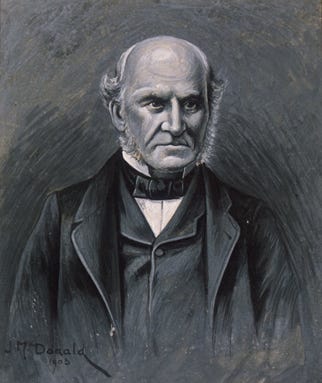

On 6 February 1840, the Treaty of Waitangi was signed by representatives of the British Crown and, initially, forty Māori chiefs. Captain William Hobson, sent by the Colonial Office in London, had arrived the week earlier. Creating for himself enough mana to lead the process of formulating a Treaty, he had just proclaimed himself to be the lieutenant-governor in what would become the new colony.

Captain William Hobson. J. McDonald, Dominion Museum, 1913, copied from the small painting presented to Auckland by the Hon. W. Mitchelson, M.L.C. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:WilliamHobsonGovNZ.jpg

Reverend Henry Williams was central to the Treaty process, being the Church Missionary Society’s leader in New Zealand, principal Treaty translator, and Treaty co-author. In 1972 an article appeared in the New Zealand Journal of History suggesting that he had attempted to play down Māori loss of sovereignty through the terminology he had employed in the Treaty. Its author, Ruth Ross, compared the wording used in the 1835 Declaration of Independence by Māori chiefs, pointing out that the clear Māori terms for sovereignty to be found in that declaration, mana, kingitanga, and rangatiratanga, did not appear in the Treaty’s Article One.

She proposed that Williams may have employed a more ambiguous term, kāwanatanga, governorship, distorting the language to overstate the powers that Māori chiefs would retain to persuade them to sign the Treaty.[2]

Lyndsey Head offered a differing perspective. She pointed out that those present would undoubtedly have had a nuanced understanding of the meaning of the different terms used and their connotations. This, after all, was what oral societies were especially good at. Meetings were often protracted, giving as much opportunity for all to undertake whatever analysis of spoken word meanings as seemed necessary or important.

In her view, the evidence suggests that the rangatira present had a sophisticated grasp of the terminology being employed. On balance, many were prepared to sign the Treaty for reasons that they and their hapū found to be sufficiently persuasive. Today, debate continues about the meaning and implications of the terminology used.[3]

Reverend Henry Williams, circa 1865. Photographer unknown. Alexander Turnbull Library. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HenryWilliams,_missionary_(1792-1867).jpg

At the Treaty’s signing, one of the most supportive Māori leaders was Ngāpuhi chief Tāmati Waka Nene. In a speech that was said to mark a turning point of the debate, swaying those present who were undecided, he addressed Captain Hobson: “you must preserve our customs and never permit our lands to be wrested from us.”[4] Even the most pro-British chiefs present would have rejected the Treaty if they were not sure it was designed to protect their traditional rights and customs, including authority over their lands.[5]

Tāmati Waka Nene by Gottfried Lindauer, 1890. Auckland Art Gallery. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gottfried_Lindauer_-_Tamati_Waka_Nene_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg

As well as Māori confirmed as possessing “the rights and privileges of British subjects”, the Māori language account, Te Tiriti, which was supposed to be the definitive version in any areas of ambiguity, also described the chiefs’ rangatiratanga or chiefly status. This made it explicit that the leaders retained their customary prerogatives. Though signing the Treaty acknowledged that the governor did have a role, the chiefs probably understood that the governor was there to work with rangatira to ensure that Māori interests were secured.[6]

Chiefs still felt some disquiet about whether they were doing the right thing. Māori grasped the tension between literate and spoken understandings of what had been discussed and felt uneasy about whether the oral perspective had been fully considered.

Later the Waitangi Tribunal would recognise this reality in its observation that “Māori would have placed more emphasis, and certainly not less, on those spoken words than on those written.”[7] Rangatira saw that despite their forensic analysis of the spoken discourse, their discussions would not be able to endure as a written document could. At the Waitangi signing, Mohi Tawhai predicted that

the written words of the Pākehā would float light like the wood of the whau tree and always remain to be seen, but the sayings of Māori would sink to the bottom like a stone.[8]

Some iwi or hapū, when asked to sign, would have relatively low-ranking rangatira put their signatures to Te Tiriti. Senior chiefs could then say, well, I wouldn’t have signed it.[9] Other iwi chose to signal that they considered their participation to have a tapu or sacred character by having their chief sign Te Tiriti with a representation of their moko rather than a written signature.[10]

The Signing of the Treaty of Waitangi by Ōriwa Tahupōtiki Haddon, 1934. Archives New Zealand. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%E2%80%9CThe_Signing_of_the_Treaty_of_Waitangi%E2%80%9D,_%C5%8Criwa_Haddon_-_Flickr_-_Archives_New_Zealand.jpg

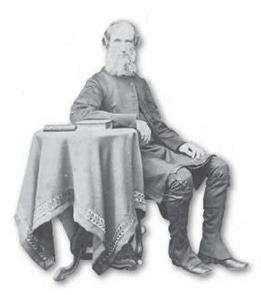

The British travelled extensively throughout the colony for several months following the sixth of February, attempting to get many chiefs not at Waitangi to sign the document. By mid-June 1840, James Busby aboard the HMS Herald had arrived at Ōtākou and requested all the local rangatira to put their name or moko on that version of Te Tiriti. Karetai and Kōrako were senior leaders present, and they were prepared to sign. While Busby was very desirous of having Taiaroa’s participation, he was elsewhere at the time and accordingly did not sign the document.[11]

James Busby. Author J.I. McDonald. National Library of New Zealand. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:James_Busby,_British_Resident_to_New_Zealand_1833-1840_(16512537759).jpg

Corruption of the Treaty

Yet soon after the Treaty was signed, government bureaucrats were already moving to commandeer then sell Māori land that was not cultivated in the European style or at least self-evidently in use in a British definition such as by being fenced. In 1846, Earl Grey, British Secretary of State for War and the Colonies said that

From the moment that British dominion was proclaimed in New Zealand, all lands not actually occupied … ought to be considered as the property of the Crown in its capacity as Trustee for the whole Community.

Henry Grey, 3rd Earl Grey, unknown photographer, 1860s. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:3rdEarlGrey.jpg

This, of course, was far from what Māori understood to be the case and contradicted other informed European perspectives such as those of the missionaries.[12]

Māori did not take this lying down, still believing or hoping at this stage that reminding the authorities of their Treaty promises would serve to see them honoured. The first Māori King Pōtatau Te Wherowhero wrote to Queen Victoria on 8 November 1847:

Oh Madam, listen! The report has come hither, that your elders (councillors) think of taking the Māoris’ land without cause. Behold, the heart is sad, but we will not believe this report, because we heard from the first Governor that with ourselves lay the consideration for our lands, and the second Governor repeated the same, and this Governor also, all their speeches were the same.[13]

Pōtatau Te Wherowhero, by George French Angas, 1847. The New Zealanders Illustrated. Alexander Turnbull Library. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:P%C5%8Dtatau_Te_Wherowhero_by_George_French_Angas.jpg

Note how the king says listen, we heard, repeated, and speeches, all referring to spoken, not written communication. In this and in other documents of the time, we can readily recognise the importance of what is said and what is heard. These comprise the heart of human agreements and relationships and are more important than what is merely written and read. Truth and honourable behaviour thus reside in that which is said and heard. Literate Europeans were unable (or perhaps unwilling) to grasp this reality.

A generation later, the same stress remained on what is spoken, not what is written, as in a letter from Tainui’s Tāwhiao Te Wherowhero, the second Māori King, to William Rolleston, Minister of Lands, on 27 August 1881. It is assumed that a trustworthy and sincere connection depends on a face to face relationship. You need both to hear a person’s spoken word and see the individual.

My word is true, I will not diverge from or conceal this word of mine. Do you look steadfastly to me; if you continually look toward me then you will hear and see, it has a day, and it will be seen.[14]

Tāwhiao Te Wherowhero by Gottfried Lindauer, circa 1885. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:King_Tawhiao_Potatau_Te_Wherowhero,_by_Gottfried_Lindauer.jpg

Within a few years of the Treaty, certain paradoxes became evident. Although British subjects had the right to sell land, the colonial authorities now required that Māori chiefs had no enforceable right over land unless they sold it to the Crown and repurchased it. If rangatira were dissatisfied with the Crown’s price, they had no right to sell it to anyone else. The Crown’s supremacy was thereby established as a property trader with unique power. No court would be well-disposed to their claim should chiefs find themselves in disputes with the Crown concerning a land sale.[15]

The War Council by Gustavus Ferdinand von Tempsky, 1864. National Library of New Zealand. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_war_council,_June_1864,_watercolour_by_Gustavus_Ferdinand_von_Tempsky.jpg

Māori saw that what had been promised as all the rights and privileges of a British subject did not convey the right to deal in acreage as other British adults could. Then the Treaty’s framers had intended that wherever Māori were in the majority, “native custom should be given the force of law”.[16] Even though Māori custom might not appear in written form, it was supposed to be accepted as fully prevailing in Aotearoa New Zealand.

The Death of Von Tempsky at Te Ngutu o Te Manu by William Potts from a painting by Kenneth Watkins, 1893. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Von_Tempsky%27s_death_Kennett_Watkins.jpg

Before 1840 many Māori had had the confidence that in future, they could well play an essential role within a thriving bicultural country. They still owned the larger part of their traditional lands and were studying and successfully adapting European economic practices. They cultivated harakeke to meet the demand for the high-quality fabrics it could provide. They grew European crops such as wheat, oats, rye, barley and potatoes, operated mills, farmed sheep, cows, and pigs, and bought and ran their own ships as coastal traders.[17]

Māori have been described as the world’s only culture that, within a single generation, made the enormous shift from a pre-mercantile status to a society that successfully created value and produced wealth in a foreign capitalist system. This represented an astonishingly fast response to new opportunities.[18]

The historian Miles Fairburn, however, would contend that the exceptional openness of Māori to employing European technologies was predictable given their previous history in Aotearoa. The argument goes that the great distance of New Zealand from Māori East Polynesian origins meant that they had fewer domesticable animals and plants than available to most Oceanic peoples.

Moreover, the New Zealand fauna and flora were much at risk from humans. Since this country was the world’s last major landmass to be settled by people, evolution here had occurred over an extraordinarily long time without any human contact. Unlike in many other places, the local plants and animal life had not co-evolved across many thousands or tens of thousands of years with hunter-gatherer society, making them less resilient and lacking time to adapt. Because the New Zealand plants and animals had not evolved alongside humans, they did not provide as many options for food and other resources to the newly arrived Polynesians.

Accordingly, in his view, in a relatively short timeframe of a few hundred years, as they adapted to the pristine ecosystem, Māori had more work to do than many hunter-gatherer societies throughout Asia, Europe, or the Americas. Māori became accustomed to constant change to keep their communities viable and ensure they were responsive to and made the most of the local ecology.

This experience, it is suggested, ensured the development of pragmatic attitudes, an openness to experimentation, an inventive approach to life, and mental aptitudes favouring an open mind. On first contact with Europeans, Māori were highly receptive to adopting and adapting new technologies, but the argument suggests they had always had these characteristics since their landing in Aotearoa.[19]

Nevertheless, a crippling burden of European diseases against which tāngata whenua had no natural immunity, a sudden economic depression in the mid-1850s, and a legal and political system that had no sympathy for their culture or economy coalesced to destabilise Māori society. In 1856 the price of wheat plummeted by three-quarters, and the market for other crops slumped to new lows.[20] A substantial commercial downturn brought very tough times to both European and Māori, but too many adverse factors were afflicting Māori society.

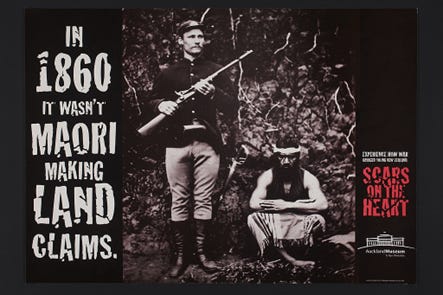

Scars on the Heart, Exhibition at Auckland War Memorial Museum, 1996. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Scars_on_the_Heart_(AM_6081).jpg

William Richmond, Colonial Treasurer and Minister of Native Affairs from 1856 to 1860, vigorously set out to undermine traditional practices whereby Māori collectively owned their land. He referred to this as their “beastly communism”, all his efforts aimed at ensuring that judicial and bureaucratic systems invariably favoured individual, not shared ownership.[21]

Christopher William Richmond and Alice Richmond, unknown photographer, circa 1863. National Library of New Zealand. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:C_William_Richmond_1863.jpg

The colony’s government and officials were waiting for the indigenous people to die out.[22] In the year of the Treaty, 1840, the Māori population was 115,000, but just six years later, it had shrunk to 109,000. In 1858 Māori were 56,000 in number, or just under half of the colony’s total inhabitants of about 115,400.[23] European diseases continued to cause a cascading decline so that by 1896 their populace reached its nadir of around 42,000.

Before any significant European contact, the South Island Ngāi Tahu population may have numbered anything up to around 20,000 persons, but population collapse would occur from factors such as disease, warfare, and profound social disruption. The year 1848, which marked the arrival of the Presbyterian Free Church Scots in Dunedin, may have marked the lowest point of the tribe’s existence, with only 1333 persons being listed by name in the archives of the Māori Land Court of 1925.[24]

During the 1840s and 1850s, a census of Ngāi Tahu might have counted 1500 to 2000 residents, of whom perhaps 300 lived in the vicinity of Ōtākou, Purakaunui and Waikouaiti.[25] It was about this time that Māori would say, “The peace of the Pākehā is more to be dreaded than his war”.[26]

Retrospective judgements of Edward Gibbon Wakefield and his New Zealand Company’s colonising schemes for Aotearoa are diverse. The historian Willie Morrell concluded that Wakefield was “half genius and half charlatan”.[27] A less equivocal assessment came from Te Āti Awa’s Professor Sir Ralph Ngātata Love. He proposed that Wakefield’s vision had resulted in Māori losing “their lands, their laws, their language, their livelihood, their very reason for being. It was total devastation”.[28]

Matiu Rei of Ngāti Toa had a similar view, referring to Wakefield as a scoundrel “who managed to pull off the biggest scam in this country’s recorded history”. His primary legacy was the “relentless pressure by the Crown to acquire Māori resources”.[29]

Edward Gibbon Wakefield. Author Albert James Allom, between circa 1850 and 1860. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Edward_Gibbon_Wakefield_c1850-60.jpg

During the 1850s and 1860s, successive attorney-generals and judges set out to contradict the Treaty’s articles and principles. It was said that the official documentation, formally signed by representatives of the British Crown and by about 500 Māori leaders, was not a legal treaty at all: it was “a simple nullity”.[30] Despite the challenges, by 1860, some iwi were still succeeding commercially, supplying goods and services to Pākehā in New Zealand and exporting to Australia, maintaining a presence in the European cash economy.[31]

Meanwhile, the settler administration aimed to acquire as much Māori land as possible. Of governor Sir Thomas Gore Browne, it has been said that “[w]ithin his limits he was a good man, but his limits were narrow, and for the most part the Māori people existed beyond them”.[32]

Thomas Gore Browne, Governor of New Zealand 1855-1861. Author John Watt Beattie, 1896. State Library of Tasmania. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Thomas_Gore_Browne.jpg

Browne attempted to mitigate the settler government’s actions, but in an ill-judged decision, he bought a block of land offered to him by a minor Te Āti Awa chief. In so doing, he ignored the objections of the senior rangatira Wiremu Kīngi Te Rangitāke and others.

This disputed sale progressed despite resolute opposition by senior chiefs, but the governor was determined not to back down. His actions were also strongly challenged by prominent missionaries, such as Archdeacon Octavius Hadfield, who reported the Te Āti Awa stance as law-abiding Christians rightfully defending their property against illegal government behaviour.[33]

Reverend Octavius Hadfield. National Library of New Zealand. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Octavius_Hadfield_(1814%E2%80%931904).png

A rapid escalation of tensions inevitably led to heightened antagonisms between Māori and Pākehā and the eventual commencement of the New Zealand Wars in March 1860. Many Europeans living in New Zealand in 1860 felt very troubled by the looming and unnecessary conflict. In April 1860, Caroline Abraham from Wellington described “the grasping and covetous Settlers who would not rest without the addition of Waitara to their settlement”.

She accurately predicted how in this war, the innocent would suffer. Still, she was shocked by the aggressive stance of the Pākehā press, which “without any remark or remonstrance on the part of the English, quite appalls one, showing as it does the spirit of the English towards other races”.[34]

Military Encampment at Mount Richmond, by G.H. Cooper, 1861. Auckland Art Gallery. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Military_encampment_at_Mount_Richmond_(1861).jpg

By October 1860, Mary Martin in Auckland had come to a similar conclusion about the press, this time in England: “It is remarkable even now while the Times calls these fine people ‘savages’ and the Guardian dismisses them with a jaunty sentence to be exterminated like all ‘savage races’ that the New Zealanders show such a singular temper and forbearance”.

She went on to point out that had Māori been “half as savage as Highlanders or Irish 200 years ago, or less, they would have poured down in might upon our out-settlements, killed the men and harried the cattle”. Instead, she pointed out how tāngata whenua were extremely restrained, especially in how they “shew marvelous respect to law and order. Their forbearance too under the bullying and incivility of many of our uneducated settlers is most remarkable”.

Mary Martin diagnosed Gore Browne’s situation accurately. While the governor had a conscience and wished to behave morally, he was a prisoner of his Anglo-Saxonist ideology. He “is really an honest English gentleman who would not willingly do anything unjust, but he is an old Indian officer with a strong feeling that the coloured races must be kept in their places”.[35]

Shooting Party, Mansion House, Kawau Island, by Charles Heaphy, 1853. National Library of New Zealand. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shooting_party_A-164-046.jpg

Sarah Selwyn in Auckland was likewise ashamed on behalf of her country:

Oh! we are sinking so low in the eyes of the Maories. Where is our good faith? Where are our assurances that the Queen would never do them wrong? It is a foul shame to mix up her name and lower the respect they are quite ready to pay to her, with this miserable degrading land jobbing.

She described how “it goes to the heart to see a noble race of people stigmatized as rebels and drawn to desperation by the misrule of those who are at the same time lowering their own people in their eyes”.[36]

Ngāti Maniapoto Survivors of the Battle of Orakau, 1864, pictured at the Jubilee Gathering, 1914. From James Cowan, The New Zealand Wars, 1922. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ngati_maniapoto_survivors_of_the_war.jpg

The British authorities had a ready-made law at hand for repressing a less powerful ethnicity. The New Zealand Suppression of Rebellion Act of 1863, confiscating large swathes of Te Āti Awa’s property in Taranaki, was a close copy of a UK act used to dispossess people in Ireland in 1797.[37]

Coming up in future posts:

The People Were Offered up as a Sordid Sacrifice on the Glittering Altar of Commerce.

The Missionary, the Bishops, and the Drunken Whalers.

A Pure City of God on Dunedin’s Unsullied Hills.

The Independence and Cheek of the Labouring Class, Particularly of Female Domestic Servants, Is Beyond All Endurance.

Squatters Rush in, Rabbits Rampant, and Too Many Flocking Sheep.

Gold, a Wedding, Injury, and One More Throw of the Dice.

An Irruption of Strenuous Men, a Ranting, Roaring Time.

But the Thief, Complete With Door, Outran Him and Disappeared into the Raggedy Ranges.

Saddle Hill: Beyond Dunedin’s Disgusting Malodorous Effluvia and a Pestilence of Blowflies.

“Well, No”, Countered The Digger, “But I’ll Give You Sixpence if You Polish Me Boots”.

A Burden Almost Too Grievous to be Borne and Making Shipwreck of Their Virtue.

The Irish Spiritual Empire, a Cycle of Sectarian Epilepsy, and a Certain Fat Old German Woman.

Better at the Language Than Those Who Owned It and Equally Determined to be Both Themselves and to Conform, Fit In.

I Found It a Matter of No Small Difficulty to Collect the Bills Due by Females Who Have Been Assisted to the Colony.

Her Skirt Would Stand up Straight By Itself and Have to be Thawed Out.

His Wife Burst into Tears, Saying She Had Already Mortgaged Their Home so She Could Pay for Her Own Dredge Speculations.

An Irresistible Feeling of Solitude Overcame Me. There Was No Sound: Just a Depressing Silence.

Norman Conceded in His Mind that the Boomerang Would Crash Home Before He Could Snatch Out His Revolver.

The Sin of Cheapness: There Are Very Great Evils in Connection with the Dressmaking And Millinery Establishments.

The Poll Tax: One of the Most Mean, Most Paltry, and Most Scurvy Little Measures Ever Introduced.

Walking as a Pilgrim: Physical, Mental, Spiritual.

Notes

[1] Sutch, The quest for security in New Zealand, p. 30; Fairburn, ‘Is there a good case’ p. 163.

[2] Ross, ‘Te Tiriti o Waitangi’; Belgrave, Historical frictions, pp. 49-50.

[3] Head, ‘The pursuit of modernity in Māori society’, pp. 105 ff.

[4] Pybus, Māori and missionary, p. 35.

[5] Orange, The Treaty of Waitangi, p. 38.

[6] Belgrave, Historical frictions, p. 65.

[7] Byrnes, The Waitangi Tribunal, p. 115.

[8] Binney, ‘History and memory’, p. 73.

[9] Professor Sir Ralph Ngātata Love, personal communication; Orange, The Treaty of Waitangi, p. 56.

[10] King, ‘Some Māori attitudes to documents’, p. 14.

[11] Ellison, ‘Māori life and leisure’, p. 74.

[12] Porter, Macdonald & MacDonald, My hand will write, p. 101.

[13] Penguin book of New Zealand letters, p. 106.

[14] Penguin book of New Zealand letters, p. 175.

[15] Sutch, The quest for security in New Zealand, p. 38; Orange, The Treaty of Waitangi, p. 103.

[16] Sutch, The quest for security in New Zealand, p. 39.

[17] Sutch, The quest for security in New Zealand, p. 30.

[18] Akenson, ‘What did New Zealand do’, p. 194; Anderson, When all the moa ovens, p. 8.

[19] Fairburn, ‘Is there a good case’ pp. 160-161.

[20] Sutch, The quest for security in New Zealand.

[21] O’Regan, ‘Old myths and new politics’; ‘Sutch, The quest for security in New Zealand, p. 39.

[22] McCarthy, Scottishness and Irishness; Sutch, The quest for security in New Zealand, pp. 39-41.

[23] Spoonley & Bedford, Welcome to our world? p. 10.

[24] O’Regan, ‘Old myths and new politics’, Chapter Two in The shaping of history.

[25] Anderson, The welcome of strangers, pp. 187-188.

[26] Sutch, The quest for security in New Zealand, p. 41; O’Malley, The meeting place, p. 230; Pool & Kukutai, ‘Taupori Māori’.

[27] Brooking, ‘The great escape’, pp. 123-132.

[28] Love, ‘Edward Gibbon Wakefield: A Māori perspective’, p. 5.

[29] Rei, ‘Edward Gibbon Wakefield: A Ngāti Toa view’, pp. 195-196.

[30] Sutch, The quest for security in New Zealand, p. 39.

[31] Orange, The Treaty of Waitangi, p. 4.

[32] Oliver, The story of New Zealand, p. 84.

[33] Stenhouse, ‘Religion and society’, p. 324; Orange, The Treaty of Waitangi, p. 144; Davidson & Lineham, Transplanted Christianity, p. 121.

[34] Porter, Macdonald & MacDonald, My hand will write, pp. 118-122.

[35] Porter, Macdonald & MacDonald, My hand will write, pp. 118-122.

[36] Porter, Macdonald & MacDonald, My hand will write, pp. 118-122.

[37] Consedine & Consedine, Healing our history, pp. 44, 94.

References

Akenson, D.H. (2002). ‘What did New Zealand do to Scotland and Ireland?’ In The Irish in New Zealand: Historical contexts and perspectives. B. Patterson (Ed.). Victoria University of Wellington, pp. 185-200.

Anderson, A. (1983). When all the moa ovens grew cold: Nine centuries of changing fortune for the southern Māori. Otago Heritage Books.

Belgrave, M. (2005). Historical frictions: Māori claims and reinvented histories. Auckland University Press.

Binney, J. (2009). ‘History and memory: the wood of the whau tree, 1766 to 2005’. In The new Oxford history of New Zealand. G. Byrnes (Ed.). Oxford University Press Australia and New Zealand, pp. 73-98.

Brooking, T. (1997). ‘The great escape: Wakefield and the Scottish settlement of Otago’. In Edward Gibbon Wakefield and the colonial dream: A reconsideration. GP Publications in association with Friends of the Turnbull Library.

Byrnes, G. (2004). The Waitangi Tribunal and New Zealand history. Oxford University Press.

Consedine, R. & Consedine, J. (2005). Healing our history: The challenge of the Treaty of Waitangi. Penguin Books.

Davidson, A.K. & Lineham, P.J. (1995). Transplanted Christianity: Documents illustrating aspects of New Zealand church history, 3rd. ed. Department of History, Massey University.

Ellison, E. (1998). ‘Māori life and leisure’. In Work ‘n’ pastimes: 150 years of pain and pleasure, labour and leisure. Proceedings of the 1998 Conference of the New Zealand Society of Genealogists. N.J. Bethune (Ed.). University of Otago, pp. 65-81.

Fairburn, M. (2006). ‘Is there a good case for New Zealand exceptionalism?’ In Disputed histories: Imagining New Zealand’s pasts. T. Ballantyne & B. Moloughney (Eds.). Otago University Press, pp. 143-167.

Head, L. (2001). ‘The pursuit of modernity in Māori society: The conceptual bases of citizenship in the early colonial period’. In Histories, power and loss: Uses of the past – A New Zealand commentary. A. Sharp & P. McHugh (Eds.). Bridget Williams Books, pp. 97-121.

King, M. (1978). ‘Some Māori attitudes to documents’. In Tihe mauri ora: Aspects of Māoritanga. M. King (Ed.). Methuen. pp. 9-18.

Love, N. (1997). ‘Edward Gibbon Wakefield: A Māori perspective’. In Edward Gibbon Wakefield and the colonial dream: A reconsideration. GP Publications in association with Friends of the Turnbull Library, pp. 3-10.

McCarthy, A. (2011). Scottishness and Irishness in New Zealand since 1840. Manchester University Press.

O’Malley, V. (2012). The meeting place: Māori and Pākehā encounters, 1642-1840. Auckland University Press.

Orange, C. (1987). The Treaty of Waitangi. Allen & Unwin Port Nicholson Press.

O’Regan, T. (1992). ‘Old myths and new politics’. New Zealand Journal of History, 26, 1, pp. 5-27.

The Penguin book of New Zealand letters. (2003). L. Lawrence (Ed.). Penguin Books.

Pool, I. & Kukutai, T. (2018). ‘Taupori Māori – Māori population change’, Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/taupori-maori-maori-population-change/print

Porter, F., Macdonald, C., & MacDonald, T. (1996). My hand will write what my heart dictates: The unsettled lives of women in nineteenth-century New Zealand as revealed to sisters, family and friends. Auckland University Press.

Pybus, T.A. (2002). Māori and missionary: Early Christian missions in the South Island of New Zealand. Cadsonbury.

Rei, M. (1997). ‘Edward Gibbon Wakefield: A Ngāti Toa view’. In Edward Gibbon Wakefield and the colonial dream: A reconsideration. GP Publications in association with Friends of the Turnbull Library, pp. 195-197.

Ross, R.M. (1972). ‘Te Tiriti o Waitangi: Texts and translations’. New Zealand Journal of History 6, 2, pp. 129-157.

Spoonley, P. & Bedford, R. (2012). Welcome to our world? Immigration and the reshaping of New Zealand. Dunmore Publishing.

Sutch, W.B. (1966). The quest for security in New Zealand 1840 to 1966. Oxford University Press.