The Missionary, the Bishops, And the Drunken Whalers

In these posts, I tell of two of my ancestors who, in 1861, arrived in Aotearoa New Zealand. My Irish great-great-grandmother Maria Dillon landed in January, just a few months before the gold rush that would utterly transform Dunedin and the province of Otago. My great-grandfather, the Scotsman Archie Sligo, was among the flood of hopeful diggers who disembarked in October of that year.

I wanted to learn more about the forces that propelled them from their homelands, what attracted them to their new country, what happened here shortly before they arrived, and what they encountered as they set about making new lives for themselves.

These posts reveal part of their stories.

Previously: The People Were Offered Up as a Sordid Sacrifice on the Glittering Altar of Commerce.

The previous post looked at the early days of the Otago / Ōtākou Block Agreement and what happened next. We now turn to the history of Otago about the time of Te Tiriti.

Just before the Treaty’s signing, on 27 January 1840, several Ōtākou chiefs, including Karetai, Te Mātenga Taiaroa, and Tūhawaiki arrived in Sydney, then known as Port Jackson. On the last day of that month, they met Sir George Gipps, Governor of New South Wales and, until the Treaty was signed, also of New Zealand.

Taiaroa Head, Otago Harbour, named after Ōtākou chief Te Mātenga Taiaroa. Photographer Sarah Stewart, 2009. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Taiaroa_Head,_Dunedin,_New_Zealand.jpg

Gipps had been growing concerned at the highly dubious transactions that Europeans disembarking in Sydney claimed to have already completed in New Zealand. He accordingly issued a proclamation that aimed to prohibit all future land sales and appointed commissioners to investigate prior purchases. Gipps offered the chiefs a treaty that would definitively hand over Aotearoa’s sovereignty to Queen Victoria, which they chose not to sign.[1]

Sir George Gipps, Governor of New South Wales and New Zealand. Portrait by William Nicholas, 1847. National Library of Australia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:George_Gipps.jpg

However, the Ōtākou chiefs were said to have added to the confusion by contracting lawyers in Sydney two weeks later to draft a so-called purchase and sale agreement. In it, they claimed to have sold the entirety of the South Island, along with Rakiura/ Stewart Island thrown in for good measure, to the local entrepreneurs William Wentworth and John Jones for a few hundred pounds.[2]

British Admiralty Chart of Ruapuke Island, Home of the Rangatira Tuhawaiki, 1857. Archives New Zealand. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Admiralty_Chart_No_2533_Ruapuke_Island_(16557355366),_Published_1857.jpg

Their more significant visit, supported by the Otago whaler and entrepreneur Johnny Jones, was to the Methodist mission in Sydney. They made a case for a missionary to be installed near Jones’ whaling base at Waikouaiti (Karitane). The rangatira knew that Māori children in North Island Anglican and Methodist missions had been learning to read and write for some years. They could see the value of literacy as a useful addition to their children’s skills and accordingly sought the same for their young people.[3]

Accordingly, Reverend James Watkin arrived on the barque Regia at Waikouaiti with his wife Hannah Watkin, nee Entwisle, and their five young children on 16 May 1840. The youngest was just ten months old. Their initial very basic lodging was at Waikouaiti, where the family would have been shocked at the pervasive rank stench of Johnny Jones’s shore whaling station.[4]

Waikouaiti Beach. Photographer Prankster, 2012. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Waikouaiti-Beach03.jpg

The Europeans comprised around forty whalers, ex-convicts from Australia, sailors, coopers (barrel makers) and carpenters. Some Māori were present as whalers, including refugees who had fled south to escape Te Rauparaha.[5]

Watkin preached his first service in English the next day. He was a gifted linguist and had prepared himself for work with Ngāi Tahu by studying texts in Māori, such as the New Zealand Testament published at Paihia, designed for the Ngāpuhi people, the northernmost and largest among the tribes. Initially, he was taken aback to discover that the language forms differed significantly from te reo as spoken by Ngāpuhi. However, he set about learning the local dialect, and within three months, his command of it was strong enough for him to be reasonably well understood.[6]

Removing Blubber From Beached Whale, by C.H. Stevenson, circa 1921. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FMIB_33966_Removing_Blubber_from_Whale_Beached_on_California_Coast.jpeg

Lacking any printing facilities or usable books, Watkin had to make his own, writing out by hand teaching and learning materials for the young Ngāi Tahu people who came to him. At hand were three significant Māori settlements at Moeraki, Ōtākou and Purakaunui, where he focused most of his attention.

Moeraki Beach. Photographer Krzysztof Golik, 2017. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Moeraki_Boulders_05.jpg

He wrote back to the U.K., remarking how heavy the bush cover was. He was struck by how many rivers and rivulets he had to cross and commented on how much warmer the winter climate was than in the northern hemisphere. Watkin was aware that he was witnessing the damage being caused to an indigenous people who were suffering great stress from European diseases. In his view,

[t]his island would, with proper culture, produce food for millions, but it is next to solitary. It has never been so prosperous as the North Island within the memory of the inhabitants, but it has been much more populous than it is now in the last ten years. The measles carried off hundreds, if not thousands, of all ages, and a ‘churchyard’ cough has been equally destructive within a few years. War has thinned their number greatly through war with the North Island natives, who appear to be more bloodthirsty than these ... Yet such is the fear of the people that scores of miles before you reach Cook Strait, which separates the two islands, you cease to meet with a native. Those who have escaped the exterminating wars waged against them by Taraupaha [Te Rauparaha] have settled here and at other places more to the southward.[7]

Reverend James Watkin, engraved by John Cochran from a photograph circa 1863. Ref: A-043-002. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/23115138

For their first four months in the Otago winter of 1840, the family of seven lived in a rough hut, initially with a dirt floor. This was succeeded by a little four-roomed cottage that served as a school where Watkin continued to study te reo. He also employed it as a place of worship where he taught “the truth of God which will banish from their minds the superstitions by which they are at present enslaved, and restrain them from acts of bloodshed, for which they have so strong an inclination.”[8]

South Sea Whalers Boiling Blubber, by O.W. Brierly, circa 1876. Cook Islands Wildlife Centre. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%22SOUTH_SEA_WHALERS_BOILING_BLUBBER_by_Oswald_Walters_Brierly_in_the_exhibition_of_the_society_of_painters_in_water_colours%22.jpg

The family’s initial period there was enormously challenging. For five months, they heard nothing from their missionary base in Sydney. They received no supplies of food or anything else, let alone the Bibles and Charles Wesley’s edition of the Book of Common Prayer that Watkin yearned for so intensely.

Reverend Watkin was very distressed at the privations of his family and the parishioners he was starting to attract. Apart from occasional support from the whaling station, they had no means to obtain their former staple diet of flour, potatoes, tea, and sugar. Hence, for months, the family lived mainly on shellfish that they could excavate from the beach or prise from the rocks, and, taught by local Māori, they cooked and ate young leaves from the heads of tī kōuka, which they came to call the cabbage tree.[9]

Tī Kōuka on Otago Peninsula. Photographer Ray O’Brien, 2022. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Otago_t%C4%AB_ko%C5%ABka_24.jpg

Reverend Watkin’s two aims were to teach reading and writing, which occupied much of his time, taking up to two literacy classes daily, and instructing people in Christianity. In addition, he had to teach concepts such as the seven-day week. While dividing time in this way was unknown to Māori, for Watkin, it was essential since he sought to establish a strict observance of the Sabbath. Watkin and other missionaries, especially those in the Protestant traditions, knew that people could not read the Bible without being literate. Only understanding and accepting the Bible would free people from their erstwhile beliefs and open heaven’s door.[10]

Hannah Watkin, from The New Zealand Methodist Times, 18 May 1940, p. 22. Reproduced with permission from Pūmotomoto: The Gateway to Knowledge https://kinderlibrary.recollect.co.nz/nodes/view/5027?highlights=eyIwIjoibXJzLiIsIjEiOiJ3YXRraW4iLCIxNCI6Im1ycyJ9&type=phrase&keywords=mrs.%20watkin#idx119882

His wife Hannah was equally busy. Along with the vast collection of home-based activities that pioneer wives and mothers had to do and parenting their five young children, she also ran many domestic arts classes, such as teaching sewing to Ngāi Tahu women and girls. In many ways, Hannah had a similar role in building cross-cultural insights among Ngāi Tahu women as her husband did with men.[11] A missionary’s wife was

often the best sort of sturdy pioneer herself, and of the greatest service in teaching Christianity and civilisation to young Māoris in the house or in school. When the missionary was away she could often act in his place.[12]

Very high expectations were laid upon missionaries’ wives. For example,

[s]he gains access where her husband cannot. By her example and deportment she raises the tone of moral feeling, enkindles a desire for knowledge and instruction, and awakens in the breast emotions that had never dwelt in it before.[13]

The Watkins built a strong cohort of Ngāi Tahu lay supporters, some of whom were later ordained, often working as intermediaries between Pākehā and Māori. Among them were famous warriors such as Tohiti Haereroa, who had fought Te Rauparaha in Marlborough and then the war leader Te Pūoho-o-te-rangi at Tuturau. He also did much to tutor Reverend Watkin in the local dialect.

Other influential backers in his community included Wiremu Potiki, a signatory to the Otago Deed of Purchase in 1844, and his wife, Mata Nera Whio.

Thought to be Wiremu Potiki, by Isaac Coates, circa 1843. National Library of New Zealand. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pitoki._Queen_Charlotte%27s_Sound._One_of_the_Council_of_the_tribe_at_Queen_Charlotte%27s_Sound,_watercolour_%26_gum_arabic_by_Isaac_Coates.jpg

Also supporting Watkin was Tione Topi Patuke, who, as a seventeen-year-old in a decisive battle with Ngāti Toa on the banks of the Mataura River at Tuturau in Southland, had shot and killed the fighting chief Te Pūoho-o-te-rangi, to Te Rauparaha’s lasting fury.[14]

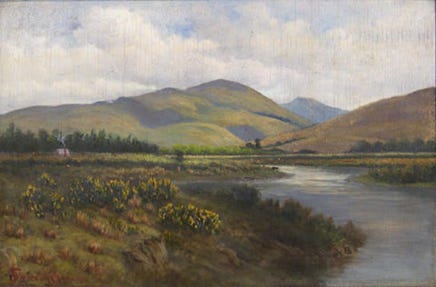

Mataura River by Frank Brookesmith, 1924. Suter Te Aratoi o Whakatū Gallery, Nelson. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Frank_BROOKESMITH_(English,_b.1860,_d.1932)_-_On_the_Mataura_River_-_Suter_Art_Gallery.jpg

Likewise noteworthy was Karetai (like Tūhawaiki, also of Ngāi Tahu and Ngāti Māmoe descent), who had successfully resisted Te Rauparaha on several occasions.[15]

However, Reverend Watkin was despondent at his difficulties coping with the whaling gangs’ drunkenness, immorality, and degenerate behaviour. The whalers had little time for him, most uninterested in a missionary’s attempts to deter them from their alcohol addiction or convince them to marry the women they were living with.[16]

The colonist and adventurer Edward Jerningham Wakefield had high praise for the whalers’ wives, commenting that they were

generally distinguished by a strong affection for their companion; are very quick in acquiring habits of order and cleanliness; facilitate the intercourse between the whalers and their own countrymen; and often manage to obtain a strong influence over the wild passions of the former.[17]

Edward Jerningham Wakefield, circa 1850. From the frontispiece of his book Adventure in New Zealand. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Edward_Jerningham_Wakefield,_ca_1850.jpg

As the months progressed, Watkin started to see some successes in persuading whalers that they should marry their Ngāi Tahu partners. As well, his literacy lessons were bearing fruit. His marriage register has survived, and it shows that “while the Māori brides could write their names in clear, well-formed letters, their Pākehā partners [mainly British or American whalers] could only make marks thus, X”. Each wedding, of course, had its legally required witnesses. When Māori witnessed the ceremonies, they usually signed their names in well-structured letters.[18]

Ngāi Tahu people had a strong desire to acquire literacy.[19] Watkin described a gathering in his home:

Tonight our kitchen furnished a scene which might have done for a painter, and which would have pleased the philanthropist and gladdened the Christian. A considerable number of young men with their books in their hands conning over their a, e, i, o, u, etc., and while I was teaching some, others of them would be soliciting the instruction of one of my little boys with ‘E ha tene, Wiriamu?’ (What is this, William?). Some of them learn rapidly and before they went away could say many of their letters.

Bishop Pompallier

The French Catholic Bishop Jean-Baptiste François Pompallier had been working in New Zealand’s north since January 1838 but knew he also needed to spend some time in the colony’s southern regions. While the main initial focus for Pompallier and his French Marist priests was missionary service with Māori, he also looked to care for Catholic Europeans to the extent possible.[20]

Bishop Pompallier, before 1871, author unknown. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pompallier_portrait_(cropped).jpg

Supported by a French schooner, the Sancta Maria, accompanied by some Marist priests, he first visited Otago in November 1840. He met a multicultural array of whalers, early farmers, and farmworkers of Irish, French, Spanish, Portuguese, English, and other ethnicities. Some non-Catholic Europeans also arrived, presenting their children to him for christening, evidently gratified to connect with a senior churchman of whatever Christian persuasion.[21]

By the time of the French bishop’s appearance in Otago, Reverend Watkin had been undertaking missionary work with Ngāi Tahu for six months. Pompallier promptly launched into what could be described as a baptism-fest, welcoming as many Māori into the Catholic fold as seemed interested. This contrasted with the Reverend Watkin’s somewhat cautious total of two baptisms in 1841 and three in 1842.[22]

Thus, the difference between Anglo-Saxon rationality and Gallic imagination: Reverend Watkin was conscientiously attempting to assure himself that those seeking baptism indeed had sincerely converted to Methodism in their minds and possessed substantial knowledge of the Bible, among other sacred texts. In contrast, the French bishop’s approach was to let the sacrament do its work: baptise first and ask questions later.

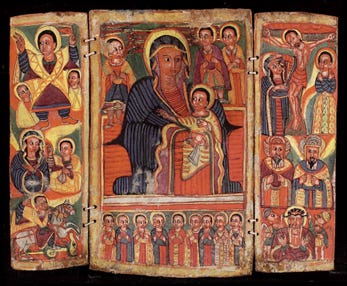

Six weeks after Pompallier’s arrival, by January 1841, Watkin reported that he had heard much about what the French bishop was telling Ngāi Tahu. In particular, Hina, the wife of the legendary ancestor figure Māui, could well have been the Virgin Mary. He wrote drily in his diary that this is “a circumstance which has been omitted in all the lives of that excellent, but much abused, woman which have ever been written.”[23]

Triptych: Ethiopian Icon of the Virgin Mary. Author unknown. Detroit Institute of the Arts. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ethiopian_-_Triptych,_Icon_of_the_Virgin_Mary_-_2002.3_-_Detroit_Institute_of_Arts.jpg

Very likely, though, the Reverend Watkin would have been highly scandalised at Pompallier’s suggestion, and perhaps this confirmed all his suspicions of an ungodly pact between papist prelates and pagans. The Catholics, at least the more liberal ones, were much more prepared than Protestants to view other cultures’ mythical heroes favourably if they saw prospects of repurposing them as Christian saints. Similarly, Reverend Watkin found it impossible to follow Pompallier’s lead in tolerating Māori traditions and customs, such as haka and tattooing.

Pompallier and his priests set out to identify local practices and beliefs that they believed were in harmony with what they understood as natural law, using these as a starting point to introduce Catholic teachings. One of their number, Fr. Claude Cognet, wrote scholarly assessments for a seminary back home of the ways in which Māori traditions could be seen as precursors of Christian revelation.[24] The Marists undermined or attacked Māori customs only when they directly contravened the Ten Commandments and other tenets of the Catholic faith.

Accordingly, they condemned cannibalism, slavery, and flagrant breaches of Christian doctrine but were relatively unconcerned about matters of lesser moment. For example, they did not tell people they had to wear contemporary British clothes in church. Pompallier remarked that it was better “to go to heaven having worn the clothes of one’s own country than to go to hell with European clothes.”[25]

The Bible, of course, was fundamental to the Catholic faith, but it was not as central as in most of the Protestant creeds. The Anglicans were likewise somewhat less focused on the factual status of the Bible. For Catholics, the Bible was not necessarily to be interpreted literally, as it had to be understood in the context of church teachings, such as its tradition and sacraments. Marist priests actively discouraged Māori from reading it. Church tradition was much more at the heart of things, or as Pompallier expressed it,[26]

the Holy Catholic Church is a heavenly store of wisdom in which we can at any time find principles quite sound in reason and faith, to apply them to circumstances of difficulties and trials which may be met during this short life.

Protestant missionaries typically maintained an uncompromisingly strict attitude to the Sabbath, exhorting their parishioners to undertake no labour on that day. Even pious travellers walking great distances through wild country would often stop and camp for the day to respect Sunday’s sacred character. In contrast, the Catholic requirement for Sundays centred around Mass attendance, with light household activities being acceptable at the service’s conclusion.[27] Whereas the Anglican and Methodist missions were clear in their intention to “civilise” Māori, challenging and confronting all superstitions as they understood them, the Marists wished to prepare Māori souls for the next world rather than attempting to produce social improvements on earth.[28]

Pompallier would have known there was no prospect of his providing a priest to follow up with and support the people he had baptised. The French Marist Fr. Jean Baptiste Petitjean, arriving in Otago on one of his occasional visits to the scattering of Catholics in the province some 17 years later in 1857, complained of how those christened had been left “like plants without water, have no more life within them”.[29] But Pompallier might have been unconcerned, perhaps holding the view that the sacrament had its own validity regardless of what happened next.

The French Marists’ nonjudgmental and bottom-up approach to their missionary work would be upended in 1871 with the arrival of the first Catholic bishop appointed to Otago, the Irishman Patrick Moran. His would be a much more top-down, doctrinaire style of pastoral work, shaped by the devotional revolution in Ireland, as a later post will report.

When it eventually dawned on Watkin that Māori were assessing the quality and relative mana of the competing Christian sects by the number of baptisms they managed to perform, he started to see how a more liberal approach had merits. He went on to christen 193 Ngāi Tahu in 1843 and another 158 before his departure the following year.[30]

Fishermen in Boats Attacking a Whale, a coloured engraving by F. Duncan after W.J. Huggins, Wellcome Collection Gallery. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fishermen_in_boats_have_been_attacking_a_whale_but_one_boat_Wellcome_V0040536.jpg

While Reverend Watkin’s main focus was ministering to the Ngāi Tahu people, he knew he could not neglect the nearby British and American whalers. Many, however, lived very dissolute lives, often in a chronic state of drunkenness, probably in response to their lives’ tedious, dangerous, and isolated character.[31]

Watkin agreed to officiate at the funeral of a whaler who drank himself to death, expiring in alcoholic delirium, but he gave the congregation more than it had asked for. He reminded the whalers that three of their boats had been wrecked recently, and eight men drowned, of whom six were so drunk they could not swim.

He told them that their addiction to alcohol day and night “sapped their vital forces, debauched their manhood, broke the hearts of their women and despoiled the lives of innocent children.” His blunt rebuke of the whalers naturally won him no friends, as he wrote in his diary: “the natives love the missionary, though some of his own countrymen curse him.”[32] But Watkin didn’t care; he was out to protect the Ngāi Tahu women from the whalers’ drunken abuse.

British Admiralty Chart of Otago Harbour, 1855. Archives New Zealand. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Admiralty_Chart_No_2411_Otago_Harbour,_(16098633363),_Published_1855.jpg

Reverend Watkin wrote in his diary that on 16 November 1840, he had conducted five services, three in Māori and two in English, “besides walking eight miles of not the easiest road in the world”. Watkin did not yet know it, but New Zealand officially became a separate colony that day. Until then, it had been administratively part of New South Wales. Shortly, it would receive a Legislative Council based in Auckland and later have its own government.[33]

The Anglican bishop George Augustus Selwyn made his first visit to Ōtākou in January 1844 and was hosted by Reverend Watkin. Selwyn was more positive than Watkin in his observations of the European whalers, noting, for example, how much these men loved their children.[34]

George Augustus Selwyn, first Anglican Bishop of New Zealand, by Mason & Co., 1867. National Portrait Gallery, U.K. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Selwyn,_George_Augustus_(1809-1878),_by_Mason_%26_Co..jpg

However, tensions and competition for converts between Anglicans and Methodists were becoming a source of scandal among Māori, as were disputes between Catholics and Protestants. Watkin said of Selwyn:

He is in labour more abundant, and journeyings often. He is an excellent traveller, can bear privation, and endure exertions which would finish some of us who are below him in station ... He laments disunion, as do I, wishes for unity, so do I, but I see not how the unity he desires is to be brought about.[35]

Coming up in future posts:

A Pure City of God on Dunedin’s Unsullied Hills.

The Independence and Cheek of the Labouring Class, Particularly of Female Domestic Servants, Is Beyond All Endurance.

Squatters Rush in, Rabbits Rampant, and Too Many Flocking Sheep.

Gold, a Wedding, Injury, and One More Throw of the Dice.

An Irruption of Strenuous Men, a Ranting, Roaring Time.

But the Thief, Complete With Door, Outran Him and Disappeared into the Raggedy Ranges.

Saddle Hill: Beyond Dunedin’s Disgusting Malodorous Effluvia and a Pestilence of Blowflies.

“Well, No”, Countered The Digger, “But I’ll Give You Sixpence if You Polish Me Boots”.

A Burden Almost Too Grievous to be Borne and Making Shipwreck of Their Virtue.

The Irish Spiritual Empire, a Cycle of Sectarian Epilepsy, and a Certain Fat Old German Woman.

Better at the Language Than Those Who Owned It and Equally Determined to be Both Themselves and to Conform, Fit In.

I Found It a Matter of No Small Difficulty to Collect the Bills Due by Females Who Have Been Assisted to the Colony.

Her Skirt Would Stand up Straight By Itself and Have to be Thawed Out.

His Wife Burst into Tears, Saying She Had Already Mortgaged Their Home so She Could Pay for Her Own Dredge Speculations.

An Irresistible Feeling of Solitude Overcame Me. There Was No Sound: Just a Depressing Silence.

Norman Conceded in His Mind that the Boomerang Would Crash Home Before He Could Snatch Out His Revolver.

The Sin of Cheapness: There Are Very Great Evils in Connection with the Dressmaking And Millinery Establishments.

The Poll Tax: One of the Most Mean, Most Paltry, and Most Scurvy Little Measures Ever Introduced.

Holy Wells: We are Order and Disorder.

Notes

[1] Orange, The Treaty of Waitangi, pp. 78, 260-261.

[2] Waite, Māoris and settlers in South Otago, pp. 38-41.

[3] Pybus, Māori and missionary, p. 1.

[4] Pybus, Māori and missionary, pp. 7-8.

[5] Pybus, Māori and missionary, p. 9.

[6] Harlow, Otago’s first book, p. 8.

[7] Pybus, Māori and missionary, p. 8.

[8] Pybus, Māori and missionary, p. 12.

[9] Pybus, Māori and missionary, p. 16.

[10] Harlow, Otago’s first book, p. 36; Lineham, Bible & society, pp. 1, 66, 83; Clarke, ‘Tinged with Christian sentiment’, p. 108.

[11] O’Malley, The meeting place, p. 160; Wanhalla, ‘Family, community’, p. 453.

[12] Thomson, ‘Some reasons for the failure’, p. 170.

[13] Grant, Representations of British emigration, p. 186.

[14] Anderson, The welcome of strangers, p. 88. Waite, Māoris and settlers in South Otago, p. 41.

[15] Pybus, Māori and missionary, pp. 43-44, 164; Crosby, The forgotten wars, p. 144.

[16] Olssen, A history of Otago, p. 27.

[17] O’Malley, The meeting place, p. 95.

[18] Pybus, Māori and missionary, p. 16; Harlow, Otago’s first book, p. 38.

[19] Pybus, Māori and missionary, p. 15; McLintock, The history of Otago, p. 121.

[20] Breathnach, ‘Irish Catholic identity’, p. 7.

[21] Brosnahan, ‘Greening of Otago’, p. 35.

[22] Olssen, A history of Otago, p. 25.

[23] McLintock, The history of Otago; Pybus, Māori and missionary, pp. 47-52.

[24] Goulter, Sons of France, p. 204.

[25] O’Malley, The meeting place, p. 183; Simmons, A brief history of the Catholic Church, p. 22.

[26] Lineham, Bible & society, pp. 68, 83, 96, 137.

[27] Olssen, A history of Otago, p. 27; Pybus, Māori and missionary, p. 61.

[28] Thomson, ‘Some reasons for the failure’, p. 169.

[29] Goulter, Sons of France, p. 45.

[30] Lineham, Bible & society, p. 41.

[31] Pybus, Māori and missionary, p. 19; Eldred-Grigg, A southern gentry, p. 76.

[32] Pybus, Māori and missionary, p. 20.

[33] Pybus, Māori and missionary, pp. 20, 32.

[34] Anderson, The welcome of strangers, p. 214

[35] Pybus, Māori and missionary, pp. 56-57.

References

Anderson, A. (1998). The welcome of strangers: An ethnohistory of southern Māori A.D. 1650-1850. University of Otago Press in association with Dunedin City Council.

Breathnach, C. (2013). ‘Irish Catholic identity in 1870s Otago, New Zealand’. Immigrants and Minorities, 31, 1, 1-26.

Brosnahan, S.G. (1998). ‘The greening of Otago: Irish [Catholic] immigration to Otago and Southland 1840 to 1888’. In Work ‘n’ pastimes: 150 years of pain and pleasure labour and leisure. Proceedings of the 1998 Conference of the New Zealand Society of Genealogists. N.J. Bethune (Ed.). University of Otago, pp. 33-64.

Clarke, A. (2005). ‘Tinged with Christian sentiment: Popular religion and the Otago colonists, 1850-1900’. In Christianity, modernity and culture: New perspectives on New Zealand history. J. Stenhouse (Ed.) assisted by G. A. Wood. ATF Press, pp. 103-131.

Crosby, R. (2020). The forgotten wars: Why the musket wars matter today. Oratia Books.

Eldred-Grigg, S. (1980). A southern gentry: New Zealanders who inherited the earth. Reed.

Goulter, M.C. (1957). Sons of France: A forgotten influence on New Zealand history. Whitcombe & Tombs.

Grant, R.D. (2005). Representations of British emigration, colonisation and settlement. Palgrave Macmillan.

Harlow, R. (1994). Otago’s first book: The distinctive dialect of Southern Māori. Otago Heritage Books.

Lineham, P.J. (1996). Bible & society: A sesquicentennial history of The Bible Society in New Zealand. The Society and Daphne Brasell Associates Press.

McLintock, A.H. (1949). The history of Otago: The origins and growth of a Wakefield class settlement. Whitcomb & Tombs.

Olssen, E. (1984). A history of Otago. John McIndoe.

O’Malley, V. (2012). The meeting place: Māori and Pākehā encounters, 1642-1840. Auckland University Press.

Orange, C. (1987). The Treaty of Waitangi. Allen & Unwin Port Nicholson Press.

Pybus, T.A. (2002). Māori and missionary: Early Christian missions in the South Island of New Zealand. Cadsonbury.

Simmons, E.R. (1978). A brief history of the Catholic Church in New Zealand. Catholic Publications Centre.

Thomson, J. (1969). ‘Some reasons for the failure of the Roman Catholic mission to the Maoris, 1838-1860’. New Zealand Journal of History, 3, 2, pp. 166-174.

Waite, F. (1980). Māoris and settlers in South Otago: A history of Port Molyneux and its surrounds. Otago Heritage Books.

Wanhalla, A. (2009). ‘Family, community and gender’. In The new Oxford history of New Zealand. G. Byrnes (Ed.). Oxford University Press Australia and New Zealand, pp. 447-464.