The Irish Spiritual Empire, A Cycle Of Sectarian Epilepsy, And A Certain Fat Old German Woman

Previously: After Some Debate, They Agreed that Killing the Priest Would Probably Bring Bad Luck.

This post examines the arrival of the Irish bishop Patrick Moran in Otago and his impact in Dunedin, the unfolding of what came to be called the Irish Spiritual Empire, how Moran’s journal The New Zealand Tablet aimed to counter prevalent Anglo-Saxonist prejudice against the Irish, and the problem of monocultural self-centredness. It explores disputes between those who supported greater centralisation in the papacy’s power and those who opposed it. Aotearoa had little of the Protestant-Catholic contention that was evident in other parts of the world, except for clashes that occurred mainly between 1916 and 1922. The principal longstanding disagreement between Catholics and Protestants was on education, which was unresolved until the 1970s. Old Irish-English battles gradually declined in their relevance to the Irish and Irish-descended.

These posts tell of two of my ancestors who, in 1861, arrived in Aotearoa New Zealand. My Irish great-great-grandmother Maria Dillon landed in January, just a few months before the gold rush that would utterly transform Dunedin and the province of Otago. My great-grandfather, the Scotsman Archie Sligo, was among the flood of hopeful diggers who disembarked in October of that year. I wanted to learn more about the forces that propelled them from their homelands, what attracted them to their new country, what happened here shortly before they arrived, and what they encountered as they set about making new lives for themselves. These posts reveal part of their stories.

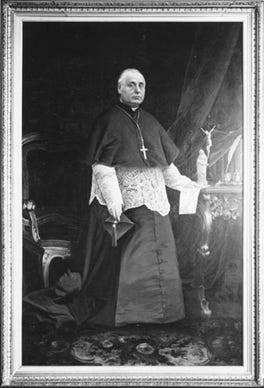

In 1871, ten years after Maria’s arrival, the Irish bishop Patrick Moran took up his post in the new Dunedin diocese, which would be his home for 25 years. Along with other Irish clerics, he had been trained in Rome. In their work over the decades in several countries, his cohort, known as the Cullenite bishops, would prove powerful advocates for the Vatican-approved version of Roman Catholicism.[1]

Piazza, St. Peter’s, Rome, 1909. Photographer unknown. Piazza, St. Peter’s

As the British Empire spread its tentacles across the globe, Irish Catholicism immediately followed. People came to call it the Irish spiritual empire.[2] Formidable prelates such as Cardinal Cullen in Dublin or Bishop Moran in Dunedin were setting out to institute an Irish religious imperium throughout the British Empire. Their doing so was often against the opposition of non-Irish clergy, especially the French Marists or English Benedictines.

Pope Pius IX and Papal Court, 1868. Photographers Fratelli D'Alessandri. Pope Pius IX

The ruling of papal infallibility had been declared just in the previous year, 1870. Bitter and protracted disputes had occurred between those who set out to centralise power within the church in the pope and his Vatican systems and those who sought to preserve local autonomy.[3]

At the time of Moran’s arrival, Irish migrants comprised fourteen per cent of the population. However, they did not stand out as highly distinct from other colonists. Their numbers were relatively small and dispersed across the country’s length and breadth. There was none of the segregation, sometimes ghettoisation, that existed in countries like Canada, the USA and Australia.[4]

Bishop Patrick Moran, photographer Gilv Cappazoni. Used with permission of Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand.

The lack of Irish noticeably congregating in Aotearoa meant that they never presented as an easy target for prejudice as happened elsewhere. Also, until Moran came, the Irish in New Zealand had been free of the close clerical direction, such as what Irish bishops had recently been instituting in Australia.[5] But Moran had a comprehensive agenda of creating an in-depth infrastructure of churches, parishes headed by priests (usually Irish), and primary schools. He straightaway proceeded to publish and preach the need for Catholics to practise their religion in ways the Irish bishops considered doctrinally correct.

Moran also set about building churches, most notably St. Joseph’s Cathedral in Dunedin. The building site on Rattray St was exceptionally challenging. It comprised a deep gully, complete with a creek, and much work was needed to level the site before concreted foundations 30 to 40 feet deep could be positioned on the bluestone reef below.

St Joseph’s Cathedral, Dunedin. Photographer Robert Cutts, 2007. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:St_Joseph%27s_RC_Cathedral,_Dunedin,_NZ.jpg

The architect was the celebrated Francis Petre. At the time, many people saw cathedrals in a way that may now seem unusual. Petre’s son stated that the building of a church is in itself an act of adoration. As such, it should convey the greatest human care and effort, illustrated by “wealth of ornament, and excellence of workmanship”. Its height, in line with the principles of Gothic architecture, tried to convey the idea of reaching up to the feet of God. (See Tither, M.C. (1938). The Roman Catholic Church in Otago. M.A. Thesis, Otago University. Dunedin Public Library and NZ Tablet, 19 Feb 1886.)

In Dunedin, Moran insisted on Mass attendance every week or more frequently, daily recitation of the rosary, and he fostered devotions to the Blessed Virgin and the Sacred Heart. His centralised religious practices differed greatly from the Marists’ acceptance of diverse spiritual traditions.[6]

Moran and his fellow Irish bishops understood that you must reach the children first to produce lasting change. Below, this post looks at Moran’s work to form an education system within which his church would have a substantial management role. He saw the closest possible connection between Irish identity and Catholicism. Because his faith was so Irish-oriented, he aimed to undermine the status and influence of the French Marists and other non-Irish clerics like the English Benedictine priests.[7] Tight Vatican-Irish control would gradually weaken what Maria had experienced as the Marist openness to less Rome-directed spirituality.

Therefore, Moran’s goal was to advance the cause and the standing of the Irish in New Zealand in parallel with his work to advance his church’s prestige and national mana. He saw no contradiction or gap between being Irish and being Catholic. In his view, if you supported the faith, you endorsed the Irish enterprise and vice versa. While he was not unsupportive of non-Irish laypersons such as English or Scottish Catholics, his identity was as an Irish prelate who happened to be in Aotearoa.[8]

His arrival in Dunedin and his confrontational style were a distinct shock to the Presbyterian colony. Father Moreau of the French Marist order had made many friends by his gentle and unpretentious manner, in which he had offended no one. Moran, in contrast, was uncaring of whom he provoked. Dunedin had not seen anything quite like him, and in many of his writings, he escalated the town’s sectarian temperature.

Dunedin responded by means such as the local newspaper, the Otago Witness, calling Cardinal Cullen, his uncle and mentor in Ireland, an “arrogant bigot”.[9] Although the newspaper referred to Cullen in the first instance, Moran was the target. Both prelates had the same aims. They said that Ireland’s or New Zealand’s so-called secular school systems were not as non-religious as they claimed to be, and likewise, the Cullenite bishops were identical in their mission to build their own schools.

Site of St Dominic’s College, Dunedin. Photograph by the author, 2024.

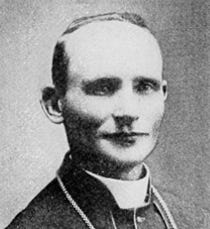

Thomas Croke, Auckland’s second Catholic Bishop between 1870 and 1874, was similarly scathing about the absence of devotional customs among his flock:

An Irish bishop was not sent here one day too soon. Had there been much more of a delay, I fear the Faith would have died out here altogether. As it is, there is a great deal of difficulty to be countered with, and many of our poor people have long since given up all the practices, and in some instances, even the profession of our holy Faith.[10]

Bishop Thomas William Croke, Photographers A. Lesage, 1870s. Bishop Croke

Note, however, how Croke refers to an Irish bishop. This can be read as an implicit criticism of non-Irish clerics, such as the Marists, who were more liberal and open to varied forms of spirituality.

Early in the twentieth century, Henry Cleary, the sixth Catholic bishop of Auckland, who did much to reduce factional tensions, used the phrase “a cycle of sectarian epilepsy” to describe Protestant-Catholic mutual antagonisms.[11] But Bishop Moran was unrepentant at the prospect of fanning the flames of denominational divisions in his more dogmatic published comments or as passionately declaimed in his Sunday sermons.

Bishop Henry Cleary, photographer unknown, 1917. The Catholic Encyclopedia and its Makers. Bishop Cleary

When it became clear to Moran that the local publications were not giving him a sufficient platform to state the Irish Catholic cause, within a couple of years, he launched his own weekly journal, The New Zealand Tablet. He was unapologetic about setting out in his assertive and authoritarian style to promote the Irish perspective and celebrate Irish culture and heritage.

As reported in earlier posts, at this time, much writing in English, both scholarly and popular, tried to advance the notion that the Irish were an inferior “race”, destined (probably by God) to be forever under Anglo-Saxon rule.

Moran’s New Zealand Tablet aimed to counter Anglo-Saxonist prejudice. It challenged the discriminatory pattern of thinking, which held that Dunedin’s dominant Anglo-Saxon and Scottish Protestant culture was neutral and possessed no social or political partiality.

For the entirety of his time in Dunedin, Moran did not hesitate to advance the idea that other frames of reference exist beyond that of the White Anglo-Saxon Protestant. He made it plain that the Irish were not about to relinquish their identity by adopting locally prevalent cultural and political perceptions.

He pointed out how a paramount culture can easily fall into the trap of believing that its assumptions and habits are the default or only ones needing to be considered. It seems to be a human characteristic that we drift into a state of monocultural self-centredness until we learn that there are other viable and acceptable ways to see the world.[12]

As well as combating the more hard-line adherents of Dunedin’s Presbyterian Free Church, Moran immediately started criticising the Marists who had preceded him. He was highly dismissive of them and was not inclined to understand how they had supported migrants like Maria to sustain their faith. In March 1871, Moran wrote of the Marists who had served before him in Otago:

The Frenchmen are good men and respectable priests, but they have the interests of their order, as they call it, to attend to, and in doing so they appear to me to have satisfied themselves with saying their prayers.[13]

Moran complained about Father Moreau because he had not done enough to buy land, build churches or establish schools. Certainly, Moreau had had other priorities, and he was relatively less concerned about Bishop Moran’s obsessions: forming infrastructure, purchasing properties, erecting churches and schools, and instituting parishes headed up by priests. Moreau did encourage Catholics throughout Otago to work to build their own churches.[14] However, his primary vocation was to respond directly to the spiritual needs of the people, such as via his numerous, weeks-long walking visits to the Otago goldfields and beyond.

Moran’s criticisms were outrageously unjust given how hard Father Moreau had worked for over ten years in serving those who sought his help throughout Otago and Southland, not least in the wilds of the goldfields. However, his disdainful comments were not so much a personal attack on Moreau as they were part of a larger national and international power struggle.

The conflict between Irish bishops such as Moran and the French Marist clergy was the local version of a prolonged international dispute in the Catholic church. This contest was between Gallicism (decentralised faith practices) and the new, Vatican-approved Ultramontane (centralised) ways to perform one’s religion. For many years, culminating during the 1860s, a debate had occurred about whether it was justified to accept a great deal of reliance on the pope and his authority.

Opposing the Vatican’s stance was the standpoint that Catholic communities beyond Rome should decide how they understood and practised their faith. On Bishop Moran’s arrival in New Zealand, a battle ensued between the Irish church, adhering to the Vatican’s Ultramontane requirement of a highly unified collection of religious norms and the French missionaries’ more tolerant and liberal approach.

St. Mary of the Angels, Wellington, in the care of the Marists. Photographer Itineris55, 2022. St. Mary of the Angels

As described in earlier posts, the Marists were open to discovering the good in others’ sacred principles, such as in te ao Māori beliefs and traditions. Marists were also international in their thinking rather than nationalistic.[15] Hence, they saw no need for and were unsympathetic towards Moran’s vociferous Irishness.

Accordingly, Patrick Moran and his successors (such as Michael Verdon, appointed as Bishop of Dunedin in 1896 and, like Moran, Cardinal Cullen’s nephew) had no tolerance for whatever remained of the Celtic Christian traditions that Maria and other Galway Irish still practised.[16]

In the decades following the Great Famine, parishes became more developed throughout the Irish international spiritual empire where the church followed migrants, such as in the USA, Canada, Australia, and Aotearoa.[17] Building programmes for parish churches and schools were especially important, paid for by parishioners. Churchgoers contributed financially at each Sunday Mass, thus funding the church schools. The state assumed few of their expenses.

Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament, Christchurch, also designed by Francis Petre, described as Aotearoa’s finest Renaissance-style building, but destroyed in the 2011 earthquake. Photographer Robert Cutts, 2007. Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament

By the dawn of the twentieth century, Moran’s organisation had completed a massive development programme. It included seven secondary and 18 primary schools, “15 parishes, 22 priests, 6 Christian Brothers, 82 nuns, 43 churches and a cathedral.”[18] Parish priests and their nuns, brothers and laity support teams established comprehensive networks of social functions, youth programmes and sports teams. They instituted charitable work for the elderly, orphans and the poor, cultural, debating and entertainment activities. All sought to sustain parishioners within a wide-ranging social setting.[19]

St Joseph’s Cathedral alongside the Dominican Nuns’ Priory. Photograph by the author, 2024.

Moran’s New Zealand Tablet served as a powerful means of socialising the faithful into an involvement with the sacraments, particularly confession, weekly Mass attendance and holy communion. Parents learned the importance of getting their children baptised and later confirmed in their faith. A regular supply of clergy and other religious personnel, such as Dominican nuns, landed from Ireland, and the schools served as a fundamental instruction ground for maintaining the faith.

St. Agnes of Montepulciano, St. Joseph’s Cathedral, Dunedin. (St. Agnes was a Dominican prioress in mediaeval Tuscany.) Photographer Lord A. Nelson, 2023. St. Agnes of Montepulciano

As the generations unfolded, the people no longer considered themselves Irish. Still, their identity as Catholics was reinforced by the schools that most attended and the social dynamics of the communities in which they socialised, played sports and created their families.[20]

Catholic and State Education

The principal and persisting dispute in Aotearoa between Catholics and Protestants was about education, which was unresolved for a century until the 1970s. The broad Protestant ideal for children’s education was that a new British colony needed a unified school system to teach and reinforce principles inherent in Christianity, particularly as in the Bible. Many Catholics would not have objected to this goal, but their problems were twofold.

First, the puritan (or “low church”) elements among the Protestants, such as Dunedin’s Scottish Free Church Presbyterians, tended to believe in the Bible’s literal truth. For them, the Bible gave a guaranteed source of direction and wisdom to the reverent churchgoer who read it.

As described in earlier posts, the Catholics also thought the Bible was central to their faith. Yet, for the most part, it was not to be taken as factually exact or as a sole guide. It needed interpretation within the context of church traditions and practices. Hence, Protestant proposals that Bible teaching should occur in schools as part of children’s training in British Christian values were unacceptable, given that this teaching would tend to emphasise literal interpretations of Bible accounts.

The Otago Provincial Council, run mainly by Free Church Presbyterians, had established and held close control over the education system, which, from their perspective, they liked to think of as secular.[21] However, in their Free Church view, while schools existed partly to develop the individual child’s capabilities, their primary purpose was to teach and uphold an appropriate Christian social discipline.[22]

In March 1856, Otago Province promulgated an Education Ordinance that specified schools as institutions within which the church would have a leadership role. For example, teachers had to hold a certificate of fitness awarded by a minister of religion. Then, schools could dismiss staff for “teaching religious opinions at variance with the doctrine of the Holy Scriptures”. The province hardened its ordinance six years later to state that in Otago schools, “no religious doctrines shall be taught at variance with what are commonly known as evangelical Protestant doctrines”.[23]

Even if teachers permitted children to remove themselves from a classroom during a Bible instruction session, the Catholic view was that schools could not be secular by their very nature. Inevitably, they would reflect the prevailing values of the society that had established and governed them. Therefore, in a Scottish Presbyterian settlement like Dunedin, an education system that insiders wanted to describe as secular would have the religious assumptions and concepts of the dominant majority threaded through it.

As often happens, outsiders may see what insiders cannot, so “the very ideology of secularism precluded its administrators from perceiving” it.[24]

Catholics believed their church’s purpose was to create good people, dispense the sacraments, teach appropriate values, encourage people in their spirituality, and interpret the Bible and other sacred texts. A basic foundation was a Catholic school system since education was not just about personal knowledge and skills. In their classrooms, children also learned a holistic and values-based approach to life, including how to serve others. As such, children’s education could not be dissociated from a faith-based objective.

St Dominic’s Priory and School, Dunedin. Photographer AnnWoolliams, 2021. St Dominic’s Priory

Yet, the possibility of an exclusively Catholic education system in such a new colony seemed pointlessly divisive and was unacceptable to many Protestants. They held that a unified national school system would provide a consistent grounding for a moral and cohesive Christian society.[25]

The Catholics’ second problem was that they could readily identify anti-Catholic content in the local school syllabus. For example, on inspecting children’s textbooks, Bishop Moran found that they cited the need for “reform in the corrupt practices and the superstitious doctrines of the Church of Rome”.[26]

The Free Church’s contention that the province’s schooling they supervised was secular was a red rag to Moran’s bull. He pointed out that the “textbooks, even the spelling book, contained statements objectionable to Catholics”.[27]

Moran’s argument also identified an injustice whereby Catholics could not, in all conscience, send their children to schools that taught an Anglo-Saxon Protestant philosophy and worldview. Instead, Catholics had to carry the load of their separate system without government support. He argued that since part of Catholics’ taxes supported children’s education, why should they pay twice for their own schools and again “for the de facto Protestant state schools”.[28]

Moran was not mollified when, six years after his arrival, Aotearoa took responsibility for primary education from the provinces, setting up a national primary education system under a Minister of Education who reported to parliament. The 1877 Education Act, also known as the Bowen Act, stated, “Teaching shall be entirely of a secular character”.

The objections by Moran and others to what they regarded as a pseudo-secular character of an education system within a predominantly Protestant colony were not resolved. The majority of Catholics felt that what they believed to be Protestant schools were unsafe for their children. The irony was that removing Catholics meant that the national system was even more uniformly Protestant in nature than it might otherwise have been.[29]

Dominican Nuns’ Chapel, Dunedin. Photograph by the author, 2024.

Even though the post-1877 primary schools were supposed to be wholly secular, the curriculum’s allegedly secular attribute:

was never tested in law so that in all probability public schools often engaged in teachings which could well have been construed by an outsider to have had more than a little to do with God.[30]

Dominican Nuns’ Chapel, Dunedin. Photograph by the author, 2024.

However, not all Catholics agreed with Moran’s position. For example, John Sheehan, a New Zealand-born Catholic MP and cabinet minister who supported the 1877 Education Act, said:

one of the grandest lessons which the colonies are teaching to the mother country is that contained in the forbearance and tolerance shown by the English, Irish and Scottish colonists towards each other, and in the forgetfulness of national and religious prejudice.[31]

John Sheehan, 1884. Photographer unknown. National Library of New Zealand. John Sheehan

Moran essentially regarded Sheehan as a traitor to the cause. Given his combative approach to the status of the Irish in New Zealand and how he was always highly energised by Ireland’s plight under English rule, perhaps he took what Sheehan had said as a personal rebuke.

The schools became central to the Irish-descended Catholics preserving their identity. As further described below, Irish Catholic evolved into New Zealand Catholic as the generations succeeded one another and were increasingly locally born. Their identity was based on Catholicism and some remaining Irish values. Their separate system comprised a cultural focal point and reinforced a sense of being distinct.

The Christian Brothers’ School, Dunedin. Photograph by the author.

To outsiders, Catholics said their schools were necessary to pass on their religion. But among themselves, they acknowledged that their schools were the bedrock of their minority culture.[32]

From Irish Catholic to New Zealand Catholic Identity

Moran seemed to be waging bygone Irish-English battles in his head. These had a declining relevance to the lived experience of the Irish or anyone else in the colony. His frequently intemperate views could catalyse sectarian-minded Protestant critics to refocus their latent Anglo-Saxonist prejudice against the Irish, Catholics, or both into overt opposition.[33]

Anti-Catholic sentiment, once surfaced by the conflict, could have created a reaction in an assertive Catholic stance on matters important to them, especially their schools.[34] Yet the vast majority of Catholics in Aotearoa and, for that matter, citizens of any religion or none, did not want to be part of a denominational struggle.[35] They felt it was enough to make a sufficient and safe life for themselves and their children in their new country.

Pope as Devil Attacking England and Ireland, Artist William Heath, circa 1827-1830. Pope as Devil

Families might learn to quote the local and greatly popular poet Thomas Bracken in their hope for freedom from sectarianism, such as in his The Bad Old Times:

“… when the nations lay/ Beneath the shadow of the Bad Old Times, / Fierce, crimson-handed Bigotry held sway - / (Curs’d mother of the blackest, foulest crimes) / And marshalled all her fiends in grim array / To nurture Hate and banish Love away”.[36]

Besides, people knew how distasteful and divisive a sectarian society could be from their previous lives. As a small minority, Catholics knew they had nothing to gain from factional warfare. McCarthy referred to “a subterranean sectarianism suffusing settler society”, but the great majority, whether Protestant, Catholic or other, were reluctant to behave in ways that would have brought it to the surface.[37]

In contrast, acrimonious religious and ethnic disputes erupted between 1910 and 1930. Perhaps the most notable among the hardliner entities that fostered sectarian conflict was the Protestant Political Association, founded in 1917 by a Baptist preacher from Australia, Reverend Howard Elliott.

Dr. James Kelly took over the Catholic New Zealand Tablet editorship the same year. He would miss no opportunity to emphasise English culpability for the plight of a conquered Ireland and continued to condemn the ongoing failure of the New Zealand government to assist with the costs of Catholic schools.

The New Zealand news media of the day were almost uniformly supportive of the British cause in World War I from its inception in 1914, echoing the jingoistic frothing of the English newspapers. However, Reverend Kelly pointed out that there were other ways to assess whether anyone could justify the war on moral or political grounds. His claims proved highly provocative to the mainstream press.

Queen Victoria, Photographers Gunn & Stuart, 1896. Queen Victoria

But Kelly also made inflammatory remarks, such as describing the deeply beloved Queen Victoria as “a certain fat old German woman”. This caused intense rage in the community and called into question Catholic loyalty to the Empire. Two years into the war, the failed 1916 Easter Rebellion in Ireland, which sought to achieve the country’s independence, also seemed traitorous to the English. It similarly refreshed old Anglo-Saxonist antipathies to the Irish.

In 1922, Auckland’s Catholic coadjutor Bishop James Liston went on trial for sedition on the grounds of anti-British sentiments aired publicly. The jury rebuked him for irresponsible remarks but acquitted him.

However, with the creation of the Irish Free State in the same year, the Irish-descended and other New Zealand citizens generally reduced their interest in Ireland’s political situation. Ireland’s relationship with the UK no longer served as a significant source of strife in Aotearoa.[38]

Bishop James Liston, photographer unknown, 1935. Auckland Weekly News and Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections. Bishop James Liston

Other than in the period shortly before, during and after World War I, New Zealand saw few and persistent anti-Irish reactions of the kind often found elsewhere.[39] As mentioned, unlike in North America, the Irish were hard to identify since, with few exceptions, they generally did not co-locate distinctively in city suburbs.[40]

During the nineteenth century, New Zealand lacked cities with over 100,000 residents, meaning there was little opportunity for ethnic groups to congregate in particular suburbs. Instead, rural and small-town settings generate more contact with more diverse citizens. This contrasts with the situations in the USA and the UK, where large cities featured ethnic clustering.[41] As the Christchurch parliamentarian William Pember Reeves pointed out, “the Irish do not crowd into towns, or attempt to capture the municipal machinery, as in America, nor are they a source of political unrest or corruption”.[42]

William Pember Reeves, photographer unknown, circa 1887. William Pember Reeves

Most Irish Catholic migrants would have favoured independence for their homeland. However, other than during the disputes between 1916 and 1922, their stated convictions were insufficient to cause much conflict. For example, few public examples of Irish migrants advocating for Irish independence occurred. The letters migrants wrote to family back home seldom referred to Irish matters, focusing instead on domestic affairs. The Irish-descended were oriented neither to nationalist nor unionist Ireland but rather to Aotearoa and their lives within it.

The relative absence of nationalistic arguments seemed to fit well with the prevailing belief that not many New Zealanders wanted to fight the old world’s wars by proxy. In addition, the more obvious difference of Māori and Chinese in New Zealand possibly comprised an easier target for the racially prejudiced.[43]

Newcomers were often impressed by how harmonious interfaith interactions were. The Irishman Thomas William Croke, the second Catholic Bishop of Auckland, commented on how:

the relations existing between the various churches are most cordial for the colonists are extremely tolerant and are most liberal and generous in their conduct towards the ministers of the different religions.

Similarly, an Anglican vicar, Vicesimus Lush, on his travels, found “the great majority of the people Romanists who all received me very cordially and I had a cup of tea at one place and dinner at another.” Early in the twentieth century, the Anglican bishop Moore Neligan wrote, “stayed at hotel kept by [Anglican] Ch[urch] people who, as usual, charged the Bishop double!” The following day, he reported, “stayed in hotel kept by RCs who, as usual, charged nothing!”[44]

Bishop Moore Neligan, 1904. From New Zealand Graphic and Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections. Bishop Moore Neligan

The historian John Stenhouse wrote how he had been

struck during recent research by the number of institutions in nineteenth-century New Zealand that tried, not always successfully, to ban or suppress discussions of politics and religion, sometimes by regulation.[45]

There seemed to be a tacit understanding that it was safer not to talk publicly about divergent religious dogmas in the interests of social harmony in the colony.

Everybody knew that Catholic and Protestant hardliners vowed and declared that the others were not proper Christians. For some, it was an article of faith that the Pope was the Antichrist, and in league with Satan, while to others, Protestants were heretics and destined for hell.

Satan as the Fallen Angel by Sir Thomas Lawrence, circa 1800. Satan as the Fallen Angel

But an unspoken agreement existed to ignore the extremists’ claims while the rest of the colony just got on with it. Later in the nineteenth century, it was evident that New Zealanders generally did not favour the idea of an established creed. Many disliked any doctrine’s claim to primacy, just as they were uneasy about any hint of religious zealotry.[46]

Bishop Moran’s confrontational behaviour did not sit well with the Otago and Southland brand of Catholicism that the tolerant French priests had shaped.[47] Moran has been described as having a “Catholicism of grievance and crisis”,[48] but his attitudes had little appeal to most Irish, such as Maria and Patrick, who had landed before him. These earlier migrants had scarcely been touched by the Irish devotional revolution as described in earlier posts and had appreciated the liberal and relaxed approach of the French Marists.

Patrick Moran tried to harness what he hoped might become a bloc vote when he stood for parliament twelve years after his arrival. But no united Catholic voice emerged, and he was not elected. Catholics largely ignored attempts at provocation from sources like the Otago Daily Times, referring as it did to Bishop Moran trying to get “all of Paddy’s pigs to market”.[49]

In time, however, Dunedin’s attitude to Moran softened. Perhaps in some ways, the Free Church Presbyterians came to recognise a kindred spirit. They acknowledged someone resolute in holding to his principles and unafraid to speak his mind. His erudition and tenacity in debating earned him respect among Otago’s university community, and even those not of his church conceded his concern for the poor and dispossessed of the town.[50]

The migrants’ interest in Irish national affairs diminished as time went by. Only a minority in the New Zealand Irish-descended population supported organisations focused on Irish affairs or politics of the day. While many priests and bishops were Irish born until the 1920s, an increasing separation became evident between lay Catholics born in Aotearoa and the primarily Irish clerics who came to minister to them.

Newly arrived Irish priests learned that the laypeople’s reverence they enjoyed back home did not apply in Aotearoa. Here, more egalitarian relationships had developed. Priests still had authority and leadership in spiritual dimensions, but they could expect little deference as of right. If they wanted respect, they had to earn it. The democratic ethos of no longer showing undue esteem to others based on their alleged status punctured newly arrived Irish priests’ assumed superiority.[51]

The Catholic church in New Zealand had become not solely but predominantly Irish, even in a modified form, mainly losing the former French influence, as the proportion of Irish bishops, priests, brothers, and nuns landing heavily outweighed other ethnicities. Yet, the culture took on a unique New Zealand identity. It rejected the repressive clerical dominance that Ireland considered normal for most of the twentieth century.

The generations born in the new country had a decreasing connection to their ancestors’ homeland. Ireland did not fade entirely, but it became less meaningful.

Regarding migrants from Ireland to Australia, Catholics of Irish descent who had been born in Australia were more likely to practise contraception than those born in Ireland. This would be another instance of people in a new country preferring to make their own minds up about issues of faith and morals. It suggests a rejection of restrictive clericalism normalised in the old country.[52]

In New Zealand, Ireland’s clerical controls never took root. The Irish historian Ciara Breathnach thought that even a generation after Maria had come to Aotearoa, the narrow and doctrinaire Catholicism that the devotional revolution had introduced in Ireland was largely unknown in Maria and Patrick’s new country.[53]

Scholars in the USA sometimes refer to pan-Catholicism, meaning a gradual unfolding from an identity based on ethnicity to one based on religion.[54] As time progressed, communities in the USA began to describe themselves less as Irish and more as Catholic, and the same phenomenon occurred among the Irish-descended in New Zealand. The people’s sense of self as New Zealand Catholics became central to their identity since their religion retained its powerful appeal as a set of faith customs.

Bishop Moran’s reforms in Otago gradually took shape during the last three decades of the nineteenth century. As this happened, Catholics were eventually redirected into narrower Ultramontane rather than Gallican spirituality. Reinforcing Bishop Moran’s efforts, a different and larger assemblage of Irish migrants would come during the 1870s as part of Premier Sir Julius Vogel’s immigrant surge, vastly outnumbering the early migrants like Maria and Patrick and their cohort of Galway Irish. The newcomers would have been more influenced by the recent clerical restructuring in Ireland, becoming trained in expectations such as weekly Mass attendance.

The Angelus, circa 1857-1859. Jean-Francois Millet. The Angelus

This meant that the faithful took part in a world of litanies of the saints, feast days, prayers for the intercession of the saints, holy days of obligation, daily rosaries, forty-hour devotions, and stations of the cross walked within the church rather than the remembered processions in Ireland to sacred outdoor sites such as venerated trees or holy wells.

Each Catholic church’s Angelus bell rang at 6:00 a.m., mid-day, and 6:00 p.m. to mark the day’s passage and call parishioners to prayer. Nine First Fridays would be observed, along with Masses that acknowledged the church’s seasons of the year.

The people were inducted into a plethora of sung and spoken prayer; it broadened their vocabulary and enriched their imaginations. Church liturgies evoked the power of the word to traverse boundaries between the profane and the sacred, each of which worlds informed the other.

Tabernacle Doors, St. Joseph’s Cathedral High Altar, Dunedin. Photographer Lord A. Nelson, 2021. Tabernacle Doors

In some fundamental ways, perhaps not much had changed. People still learned that at their birth, God himself had appointed a guardian angel to accompany and protect them; they still knew the divine lay just beyond the margins of the human senses, and the spirit realm was as authentic and meaningful as the world of their everyday perceptions.[55]

It may be that for some among the New Zealand Irish, the guardian angel took the place of Ireland’s hidden people, the daoine maithe. Both were beings who, although unseen, were actual and influential in one’s life.

Southern Consort of Voices, Dominican Nuns’ Chapel, Dunedin, 5 May 2024. Photograph by the author.

Coming up:

Better at the Language Than Those Who Owned It and Equally Determined to be Both Themselves and to Conform, Fit In.

I Found It a Matter of No Small Difficulty to Collect the Bills Due by Females Who Have Been Assisted to the Colony.

Her Skirt Would Stand up Straight By Itself and Have to be Thawed Out.

His Wife Burst into Tears, Saying She Had Already Mortgaged Their Home so She Could Pay for Her Own Dredge Speculations.

An Irresistible Feeling of Solitude Overcame Me. There Was No Sound: Just a Depressing Silence.

Norman Conceded in His Mind that the Boomerang Would Crash Home Before He Could Snatch Out His Revolver.

The Sin of Cheapness: There Are Very Great Evils in Connection with the Dressmaking And Millinery Establishments.

The Poll Tax: One of the Most Mean, Most Paltry, and Most Scurvy Little Measures Ever Introduced.

Holy Wells: We are Order and Disorder.

God is Good and the Devil’s Not Bad Either, Thank God.

Notes

[1] Breathnach, ‘Irish Catholic identity’, p. 1; Simmons, A brief history of the Catholic Church, p. 61.

[2] Akenson, Half the world from home, p. 160.

[3] Simmons, A brief history of the Catholic Church, pp. 63-66.

[4] O’Farrell, ‘Varieties of New Zealand Irishness’, p. 34.

[5] Fraser, To Tara via Holyhead, p. 65.

[6] Breathnach, ‘Irish Catholic identity’, p. 4; O’Farrell, ‘Varieties of New Zealand Irishness’.

[7] Breathnach, ‘Irish Catholic identity’, p. 3.

[8] Akenson, Half the world from home, p. 175; Sweetman & Freedman, ‘Our Lady of the Antipodes’.

[9] Breathnach, ‘Irish Catholic identity’, p. 11.

[10] McCarthy, Irish migrants in New Zealand 1840-1937, p. 247.

[11] O’Connor, ‘Sectarian conflict’, p. 3.

[12] Molloy, ‘Victorians, historians and Irish history’, pp. 153-6.

[13] Sweetman, ‘How to behave among Protestants’, p. 91.

[14] Roberts, The history of Oamaru, p. 144.

[15] Fraser, To Tara via Holyhead, p. 64.

[16] Jackson, Churches and people, p. 86.

[17] Barr, ‘Imperium in imperio’, p. 625.

[18] Breathnach, ‘Irish Catholic identity’, p. 19.

[19] Devine, To the ends of the earth, p. 132.

[20] Breathnach, ‘Irish Catholic identity’, p. 19.

[21] Lineham, Bible & society, p. 54; Breathnach, ‘Irish Catholic identity’, p. 13.

[22] Patterson et al., Unpacking the kists, p. 134.

[23] McKenzie, ‘We have an anomaly’, pp. 84-5.

[24] Akenson, Half the world from home, p. 176.

[25] Lineham, ‘The nature and meaning of Protestantism’, par. 35.

[26] Breathnach, ‘Irish Catholic identity’, p. 12.

[27] Clarke, ‘Tinged with Christian sentiment’, p. 128; McLintock, The history of Otago, p. 520; Olssen, A history of Otago, p. 75.

[28] Akenson, Half the world from home, pp. 184, 176; Fraser, To Tara via Holyhead, p. 63.

[29] Lineham, Bible & society, p. 96; Akenson, Half the world from home, p. 169.

[30] McKenzie, ‘We have an anomaly’, p. 87.

[31] McCarthy, Scottishness and Irishness, p. 145; Sweetman, ‘How to behave among Protestants’, p. 92; Simmons, A brief history of the Catholic Church, p. 92.

[32] Akenson, Half the world from home, pp. 169, 190.

[33] O’Connor, ‘Sectarian conflict’, p. 3.

[34] Fraser, To Tara via Holyhead, p. 62.

[35] Jackson, Churches and people, p. 77.

[36] Bracken, T. (1893). The Bad Old Times.

[37] McCarthy, Scottishness and Irishness, p. 128.

[38] Davidson & Lineham, Transplanted Christianity, pp. 249-253; Sweetman, ‘Kelly, James Joseph’.

[39] McCarthy, Irish migrants in New Zealand 1840-1937, p. 5.

[40] Consedine & Consedine, Healing our history, p. 30.

[41] Phillips & Hearn, Settlers, p. 143.

[42] Akenson, Half the world from home, p. 55.

[43] McCarthy. Irish migrants in New Zealand 1840-1937, pp. 218, 234; McCarthy, Scottishness and Irishness, p. 210.

[44] McCarthy, Irish migrants in New Zealand 1840-1937, pp. 240-1.

[45] Stenhouse, ‘The controversy’, p. 49.

[46] Stenhouse, ‘Introduction’. In Christianity modernity and culture, p. 13.

[47] O’Farrell, ‘Varieties of New Zealand Irishness’, p. 34.

[48] Fraser, To Tara via Holyhead, p. 70.

[49] Jackson, Churches and people, pp. 90-1.

[50] King, God’s farthest outpost, p. 99; Simmons, A brief history of the Catholic Church, p. 67.

[51] Jackson, Churches and people, pp. 39-40.

[52] Jackson, Churches and people, pp. 92, 145; Akenson, Half the world from home, p. 161.

[53] Breathnach, ‘Irish Catholic identity’, p. 6.

[54] O’Day, ‘Imagined Irish communities’, p. 257. in MacRaild, D. M., & Delaney.

[55] O’Farrell, Vanished kingdoms.

References

Akenson, D. H. (1990). Half the world from home: Perspectives on the Irish in New Zealand, 1860 to 1950, Victoria University Press.

Barr, C. (2008). ‘‘Imperium in imperio’: Irish episcopal imperialism in the nineteenth century’. English Historical Review, CXXIII, no. 502, pp. 611-650.

Bracken, T. (1893). The bad old times, in Musings in Maoriland (2016). The Bad Old Times | NZETC (victoria.ac.nz)

Breathnach, C. (2013). ‘Irish Catholic identity in 1870s Otago, New Zealand’. Immigrants and Minorities, 31, 1, 1-26.

Clarke, A. (2005). ‘Tinged with Christian sentiment: Popular religion and the Otago colonists, 1850-1900’. In Christianity, modernity and culture: New perspectives on New Zealand history. J. Stenhouse (Ed.) assisted by G. A. Wood. ATF Press, pp. 103-131.

Consedine, R. & Consedine, J. (2005). Healing our history: The challenge of the Treaty of Waitangi. Penguin Books.

Davidson, A.K. & Lineham, P.J. (1995). Transplanted Christianity: Documents illustrating aspects of New Zealand church history, 3rd ed. Department of History, Massey University.

Devine, T.M. (2011). To the ends of the earth: Scotland’s global diaspora 1750-2010. Allen Lane.

Fraser, L. (1997). To Tara via Holyhead: Irish Catholic immigrants in nineteenth century Christchurch. Auckland University Press.

Jackson, H.R. (1987). Churches and people in Australia and New Zealand 1860 to 1930. Allen & Unwin / Port Nicholson Press.

King, M. (1997). God’s farthest outpost: A history of Catholics in New Zealand. Penguin Books.

Lineham, P. (1993). ‘The nature and meaning of Protestantism in the New Zealand culture’, Turnbull Library Record, 26, 1, pp. 59-75.

Lineham, P.J. (1996). Bible & society: A sesquicentennial history of The Bible Society in New Zealand. The Society and Daphne Brasell Associates Press.

McCarthy, A. (2005). Irish migrants in New Zealand 1840-1937: ‘The desired haven’. Boydell Press.

McCarthy, A. (2011). Scottishness and Irishness in New Zealand since 1840. Manchester University Press.

McKenzie, D. (1998). ‘We have an anomaly: The real cost of schooling in nineteenth century Otago’. In Work ‘n’ pastimes: 150 years of pain and pleasure labour and leisure. Proceedings of the 1998 Conference of the New Zealand Society of Genealogists. N.J. Bethune, (Ed.). University of Otago, pp. 83-96.

McLintock, A.H. (1949). The history of Otago: The origins and growth of a Wakefield class settlement. Whitcomb & Tombs.

Molloy, K. (2002). ‘Victorians, historians and Irish history: A reading of the New Zealand Tablet 1873 to 1903’. In The Irish in New Zealand: Historical contexts and perspectives. B. Patterson (Ed.). Victoria University of Wellington, pp. 153-170.

O’Connor, P.S. (1967). ‘Sectarian conflict in New Zealand, 1911 to 1920’. Political Science, 19, 1, pp. 3-16.

O’Day, A. (2007). ‘Imagined Irish communities: Networks of social communication of the Irish diaspora in the United States and Britain in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries’. In Irish migration, networks and ethnic identities since 1750. D.M. MacRaild, & E. Delaney (Eds.) Routledge, pp. 250-275.

O’Farrell, P. (1990). Vanished kingdoms: Irish in Australia and New Zealand: A personal excursion. New South Wales University Press.

O’Farrell, P. (2000). ‘Varieties of New Zealand Irishness: A meditation’. In A distant shore: Irish migration and New Zealand settlement. L. Fraser (Ed.). University of Otago Press, pp. 25-35.

Olssen, E. (1984). A history of Otago. John McIndoe.

Patterson, B., Brooking, T. & McAloon, J. with Lenihan, R. & Bueltmann, T. (2013). Unpacking the kists: The Scots in New Zealand. McGill-Queen’s University Press & Otago University Press.

Phillips, J. & Hearn, T. (2008). Settlers: New Zealand immigrants from England, Ireland and Scotland, 1800 to 1945. Auckland University Press.

Roberts, W.H.S. (1890/ 1999). The history of Oamaru and North Otago, New Zealand, from 1853 to the end of 1899. Andrew Fraser.

Simmons, E.R. (1978). A brief history of the Catholic Church in New Zealand. Catholic Publications Centre.

Stenhouse, J. (2005). ‘Introduction’. In Christianity, modernity and culture: New perspectives on New Zealand history. J. Stenhouse (Ed.) assisted by G. A. Wood. ATF Press, pp. 1-22.

Sweetman, R. (1996). ‘Kelly, James Joseph’, Dictionary of New Zealand biography. Te Ara - the encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/3k6/kelly-james-joseph

Sweetman, R. (2002). ‘How to behave among Protestants: Varieties of Irish Catholic leadership in colonial New Zealand’. In The Irish in New Zealand: Historical contexts and perspectives. B. Patterson (Ed.). Victoria University of Wellington, pp. 89-102.

Sweetman, R. & Freedman, P.F. (2001, Nov-Dec). ‘Our Lady of the Antipodes’. New Zealand Geographic, 54, https://www.nzgeo.com/stories/our-lady-of-the-antipodes/