Part Two of the James Grant Story: Can 21st-Century AI Visualise 19th-Century Prose?

Here I'm playing with AI. (Or is AI playing with me?)

In the preceding post, The Strange Life and Death of Dunedin’s James Grant, Part One, I described the extraordinary contribution Grant made to the city. Now, I examine some subjects he wrote about and explore how well 21st-century AI visuality can depict 19th-century literate prose.

These posts tell of two of my ancestors who, in 1861, arrived in Aotearoa New Zealand. My Irish great-great-grandmother Maria Dillon landed in January, just a few months before the gold rush that would utterly transform Dunedin and the province of Otago. My great-grandfather, the Scotsman Archie Sligo, was among the flood of hopeful diggers who disembarked in October of that year.

I wanted to learn more about the forces that propelled them from their homelands, what attracted them to their new country, what happened here shortly before they arrived, and what they encountered as they set about making new lives for themselves. These posts reveal part of their stories.

Evolution versus Creation

As reported in the previous post, J.G.S. Grant authored and published several journals during his life in Dunedin. A well-known one was his Delphic Oracle, and in its first issue, Grant defined his stand on the spirited contemporary debate that was then underway on evolution versus the religion of the creationists.

Could humanity have descended from lower lifeforms, as some, such as Charles Darwin and Thomas Huxley, were contending? If so, what did this mean for the Old Testament’s Book of Genesis and its account of divine intervention in creating humankind?

Charles Darwin satirised as an ape. Hornet magazine, 22 March 1871. Charles Darwin

Grant did not side with either position but instead, as a master contrarian, formulated his own stance. He seems to say evolution could be true, but that doesn’t mean you have to believe in it.

In fact, Grant might have been persuaded intellectually by the evidence of Darwin and others that humans share a common ancestry with other primates. However, he rejected any such conclusion on philosophical and aesthetic (not religious) grounds. In his view, “the noblest class of writers” had traced people’s descent from the gods within “whose peculiar care he [humankind] has ever been”.

However, a claim that we descended from apparently lesser lifeforms that takes no account of Grant’s highly cultured perspective was “mean and degrading”. He appeared aligned with the poet John Keats, for whom something beautiful, intellectual or otherwise, possesses an aesthetic truth, even though it doesn’t have to be literally true.

John Keats. Painter Joseph Severn, circa 1821-3. National Portrait Gallery. John Keats

For Grant, perspectives on human origins based on evolutionary theory were too banal and dissatisfying. Hence, he said,

[a]ccording to this class of writers [such as Darwin] such a thing as spirit, mind, soul, or intellect, in the immortal acceptation of that divine essence, is altogether out of the question. We are perfectly aware that this theory finds much outward support from the villainously low mental development of a large class of mankind. But, nevertheless, to a reflective mind this idea of man’s origin is so repulsive and abhorrent that it cannot merit any serious labour of refutation.[1]

So Grant’s first post in his Delphic Oracle marked a foundational statement for his philosophy. He said, “Humanity and divinity mysteriously commingled from the warp and woof of the Greek philosophy, literature, science, poetry, and art”. For Grant, the ancient Greeks laid a baseline standard against which 19th-century modernity had little chance.

From Literate to Visual-Tactile-Oral

In the 1960s, the Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan set out to explain how our current era is slowly distancing itself from print-oriented ways of thinking. He proposed that we are increasingly reverting to an earlier epoch of visual, oral, and tactile ways of making sense of what we experience around us and communicating with others. Where we land on in all this, he thought, somewhat resembles how people used to communicate in old pre-literate eras.

McLuhan also famously made the point that the medium is the message. He was advancing the idea that “the form of a medium embeds itself in the message, creating a symbiotic relationship by which the medium influences how the message is perceived.”[2]

Marshall McLuhan with and on television. Photographer Bernard Gotfryd, 1967. Marshall McLuhan

Some, however, believe our language shapes our mental capability. The argument goes that if our language is impoverished by becoming increasingly constrained, repetitive, and predictable, our minds and inner lives are likewise diminished. Our existence is being routinised to experience only:

banality and mediocrity. This is what our society now emphasizes and rewards: run-of-the-mill statements, canned remarks, uniform pronouncements, recitations of creeds and commandments, ready-made soliloquies, stories or arguments obtained through the mere application of stylistic recipes.[3]

In contrast, James Grant was writing at the peak of high literacy in English. I suspect the complexity of his prose (and that of many other 19th-century essayists) would defeat most of us these days. This led me to try playing with pictures to see if I could introduce and interpret his thinking.

Artificial Intelligence Sets Out to Visualise 1860s Texts

The dispute about creationism versus evolution that Grant was interested in continues in some circles. But, in any event, I wanted to make some 21st-century pictorial sense of how homo sapiens had descended from less evolved lifeforms.

However, first, I had to reflect on how a critique is emerging, a backlash against AI visual design, and a claim that human creativity deserves to be insulated from the mindless machine. For example, the Comic Arts Festival in Perth recently stated that it would not accept AI-generated media since, as they said, “All current widely available generative AI programs have been trained on stolen data, including the art and writing of our colleagues”.[4]

There’s also a generation gap. OK, old-timers, they’re saying, let’s call what you’re doing with AI “boomer art”; we in the rising generation want to do our own thing.[5] Others are happy to admit that we’re latter-day Luddites, but we embrace that term. We need to fight against the emergence of a gig economy that threatens to displace and marginalise creative workers.[6]

Then, we may be intrigued by the enticements of a super mega brain, but if it’s impossible to figure out how AI arrives at what it achieves, how does that add to the sum of human understanding or capability?

Even though I accepted the validity of the anti-AI position, I still wanted to build my own understanding by exploring what AI imagery could do. So, I inserted a query into Copilot, a Microsoft AI, asking it to visualise how Darwin understood human evolution.

It arrived at the following rather confusingly festive picture. The numbers above and below the marching figures seem to make little sense, but then the images don’t convey much either, at least to me. (Yet how do I get to look more like the fifth individual from the left?)

(It seems that Copilot is a divergent thinker like Mr Grant, given its own quirky version above of the ascent of man, as some used to call it.)

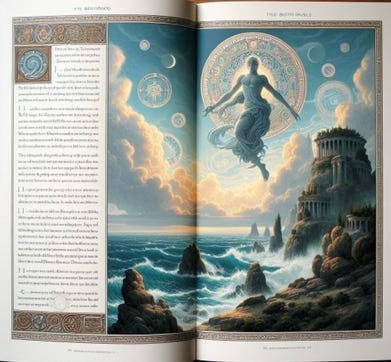

Emboldened by Copilot’s evident abilities, I wondered how it might cope with picturing the entirety of what Grant had to say on page one of his periodical, The Delphic Oracle. Here he attempts to outline the perspectives of all three of the evolutionists, creationists, and philosophers who drew attention to the interplay between gods and humans. Once I’d input all the text, I queried, how would you visualise that page?

In harmony with our digital era, as soon as Microsoft’s Copilot read Grant’s words, it seemed to get a surge of whatever passes for blood amid the rollicking bits and bytes that scamper about the hardware comprising its brain:

Copilot’s imagining of the Delphic Oracle, no. 1, page 1.

James Grant might have liked Copilot’s lush, over-the-top depiction of a fantasised past. It might not have troubled him that the figure floating over the seascape had bizarre fingers and apparently only one leg. Perhaps the scene would have evoked some feelings resounding with his beliefs about the mysterious commingling of Greek philosophy, literature, science, poetry, and art.

However, he would not have accepted dogmatic carryings-on from the opposition party, the creationists. He would have ruthlessly ridiculed their fervid fantasy that in primeval times, meat-guzzling dinosaurs frolicked harmlessly with immaculately white-clad (never mind the dinosaur, why could my kids never keep their clothes that clean?) prehistoric infants:

Children and Dinosaur, Creation Museum, Kentucky. Photographer Acdixon, 2014. Children and Dinosaur

Next, on Delphic Oracle’s page 2, Grant set about critiquing a class of archaic philosophers, astrologers, that is, who “directed their observations to the stars, in hope of throwing light on the mystery of man’s futurity”. He agreed that their astrological observations lacked an empirical foundation, yet he felt that their focus on the dignity of human nature was more meaningful than any scientifically based account of humankind could be. How to depict his observation?

The Delphic Oracle, no. 1, p. 2.

When I asked it to visualise the words on Grant’s page two, Copilot didn’t do such an exuberant job as it had achieved for page one. Instead, it abruptly changed tack and shifted its focus from the script to the consumer, as they say, of that text, i.e., me.

I had to admit that its image summed up my baffled response to his writing.

Copilot’s imagining of the Delphic Oracle, no. 1, page 2.

Well, I certainly know what James Grant is saying here, Frank, but you don’t, right, since you asked me to depict it for you? I won’t chop logic with you, so let’s just focus on what’s important and show you, Frank, something about your actual skill levels. Ponder the squirrel. I won’t say any more at this time.

I muse a little about how early initiatives to design AI systems were inspired by the goal of revealing more about how the human brain works. Neuroscientists and computer scientists hoped that if they could get machines to process information in the same ways as (we think) we do, they’d better understand how our fiendishly complex brains actually work. For example, is the brain’s corporeal functioning sufficient to explain the mental experiences in our minds? Then, as some ask, could every living thing possess its own proto consciousness?

Despite all the researchers’ systematic labours, though, it seems that we are still just speculating about how the brain’s neural activity may generate mind or explain human consciousness. Don’t even ask the scientists to conjecture about how Jung’s theory of a collective unconscious will muddy the cognitive waters even further.

Carl Jung. Comet Photo AG (Zürich), 1955. ETH-Bibliothek. Carl Jung

Instead, now operating alongside us, we’ve created a new species on the planet called artificial intelligence, which also can think in its own way. Likewise, we don’t know how it works either. Yet some believe that once AI attains a certain level of processing complexity, it will flip into its own version of consciousness (if it hasn’t done so already).

It may be possible for artificial entities to be intelligent in ways that humans cannot comprehend. If a human mind is not intelligible, say to other animals such as our household pets, it’s conceivable that an artificial mind will be inscrutable to us.[7]

So I see here a squirrel that AI has materialised from some ethereal milieu beyond the text and beyond the ken of humankind’s rickety deliberations. Evidently, the AI had to convey the hard truth that it would expect a squirrel to understand the printed word better than me. You can see that I’m bemused, but the squirrel is enlightened. Perhaps I’m a living example of how they say that Google makes you stupid.

Astrology

In the following pages of the Delphic Oracle’s first issue, Grant hunted down both ancient and contemporary varieties of the astrologers’ claims. While the mills of logic and science may grind slow, they do grind fine, leading him to the boring but necessary conclusion that astrology’s assertions rest on no secure foundation.

He went on to debunk astrological practices, using the Stoics’ arguments in particular, but holding that we are all “mysteriously related to every object, seen or unseen, beneath, around, and above” us. Yet, in so doing, Grant arrived at a stance not too dissimilar to present-day thinkers who reject the notion of humankind’s special and privileged prominence. That’s the message, folks; we’re not at the apex of all living entities.

Instead, Grant aligned himself with those cultures, especially indigenous ones, which have been much better at honouring our affinity and kinship with other living things and the earth itself than Western industrial society has been able to acknowledge.

Carl Jung quotation, source Michael Nuccitelli. Carl Jung

Still hoping for illumination, I ask the Microsoft AI how it imagined page four, and here, it may have struggled a teeny bit with visualising Grant’s opaque prose. Yet, since it’s a new smart entity on the planet, it’s not about to admit any shortcomings. At least for the time being, it still wants to establish its creds with us. (We, benignly indulgent of our failings, still like to esteem ourselves as homo sapiens sapiens.)

So, the AI employed its access to vast troves of humankind’s visual outputs over the last few millennia and transmuted the words on the Delphic Oracle’s page four into an image. Implicitly, it suggests I can’t always deliver quality, but I can do quantity.

Copilot imagining for the Delphic Oracle volume one, page four.

Hence, it generates a picture of something like, but nothing really like, the Taj Mahal. In front, people are densely arrayed and are led, it seems, by a white-clad guru. Weirdly symmetrical clouds form the backdrop. A central pool between the architecture and the crowd enigmatically reflects some but not all of the personages in the foreground.

What is Copilot intimating? Could it have taken to heart Matthew 22:14, Many are called, but few are chosen?

Moving right along, I asked Copilot to summarise The Delphic Oracle’s page five in 50 words or fewer, and it came up with a snappy 47-word effort: “The text disputes astrology’s influence on human traits and destiny, arguing that genetics and environment are more decisive. It highlights the varied lives of those born at the same moment and the ability to transcend natural limitations, suggesting astrology’s impact is overstated and questioning its predictive validity”.

I requested an image that summed up the text, and sure enough, Copilot supplied a delirious visual imagining, hotly followed by a confusion of words that made no sense, at least to someone probably over-schooled in literacy like me. I’m learning that I must transition from reader to viewer. Is that the message for us all in the first quarter of the 21st century?

Copilot’s imagining of the Delphic Oracle, no. 1, page 5.

Let’s accept, though, that once it tightens up its act, AI may finally win at the game of supplying and interpreting visual representations such as the ones we’re playing with here.

If this happens, will McLuhan be confounded, and will actual words come once again to human communication’s forefront? Should illustrators become redundant, will wordsmiths, such as poets and lyricists who can evoke deeper and subtler meanings than even the canniest AI, become (re)honoured by society?

Delphic Oracle, no. 1, page 7.

His Views on the Media

James Grant had no time for the press of the day: “Colonial journals wax and wane like the moon, and their reveries are the veriest moonshine”.[8] He lumped newspaper editors in the same contemptible category as the judiciary and the ministry:

Shareholders of newspapers plume themselves in having secured the services of idiotic cyphers and empty-headed snobs, whose inconsistent and ridiculous articles will never disturb their dreams with visions of libel and gentlemen of the long robe in the local courts of law. The editor, the judge, and the parson manipulate the press so adroitly that no whisper of wrongs and vices can ever reach the public ear. In a word, the public conscience is drowned in spurious liquor, and poisoned with false teaching, and lulled into lethal sleep by bad example during the week, and by unfaithful, cowardly, and unmanly preaching on the Sabbath.[9]

The Delphic Oracle permitted Grant to get into his stride, critically measuring the media and finding it wanting. It seemed that newspapers were beyond redemption. He declared war on media owners, declaring how they:

convey in a loathsome rill the wretched contents of the sensation tales of the day. The weekly papers do the very same. Each of these periodicals is conducted on the most selfish, prejudiced, and partial principles. They are severally owned by members of the Provincial or General Parliament, or carried on by a joint stock company, as is the case of the Otago Times and Witness; or conducted by private parties on the most venal principles. Given an advertisement from the village baker, grocer, or draper, next day appears a puff in the local column of paragraphs. The column set apart for the leader is stuffed with either toadyism towards its patrons, or with inflated notions of the importance of village or district where it is backed up with advertisements.

Still not seeking to make too many friends locally, he suggested that “the settlers had sunk into such a state of barbarity and stupidity”, and the tone of a newspaper

reminds one of the very melodious articulations of the Australian laughing jackass … [kookaburra] the journals’ sadly disagreeable croakings … whose perusal can never fail to poison the intellect and to mar the beauties of composition, which is an infallible index of the culture and fecundity of the Mind.

Grant could, though, visualise what New Zealand’s weekly and daily media could provide:

Those forty-five journals well-written and honestly managed, could work a marvellous moral reformation in these islands. They might become circulating libraries of learning; but, alas, every nobler inspiration is extinguished in the unhallowed thirst for gain, and petty power, and selfish aggrandisement. Such is the state of journalism in this colony, and such are the habits and characteristics of its editors and proprietors.

He proposed that his fellow journalists in Dunedin were “vapid, editorial storks, who can scarce write a grammatical sentence, and are singularly devoid of any sort of literary talent, even the lowest”.[10]

I thought, what the heck is a vapid editorial stork? What does that even look like? Maybe AI can tell me. So I asked MS Copilot how its digital cogitations might render Grant’s journalists:

Copilot’s imagining of Grant’s vapid editorial storks.

Looking closely, the AI seems a little muddled about which side of the typewriter is which, but perhaps James Grant wouldn’t have cared. He’d probably say that Copilot is just reinforcing the point he’d have made, being that the journalists don’t know which part of the machine they’re supposed to use.

Grant was assiduous in his attempts to be elected to parliament but was unimpressed at never succeeding. “After a labour of fourteen years, I’m pretty much disgusted. People here have done a great deal to crush me down, to knock me into the dust; but this I can say, if I had a beer barrel at my back I would now have been elected. [Here, he was referring to his rivals allegedly bribing potential voters with alcohol.]

He set out to make his views known in a public oration following his failure at the parliamentary elections, referring to “[t]he crawling editor of The Independent – a man hoary-headed and crawling onto the sepulchre – but who still dared to preach up the artificial distinctions of society in this country … I never felt more melancholy than when I saw the solemn – I had almost said the blasphemous – burlesque of an undertaker with a mourning coach conveying drunkards to the poll. If I have spoken truth to the people – and I believe that I have, those who have persecuted me, and torn the bread out of my mouth, will, in due time, meet their reward”.[11]

Copilot’s imagining of the Delphic Oracle, 8 March 1869, p. 53.

At this point, Copilot tried to get into the swing of things and took Grant’s OTT style to its alphanumeric heart. The oddities in the AI image above are probably too many to list, but they include the horse, which is afflicted with a strange, misplaced, misshapen hoof, the gentleman at the far right who is miraculously levitating and the affluent, elderly chap at the top left who seemingly is groping the fellow beside him.

Grant showed no interest in making friends among the local political caste. For example, he reported that Otago’s Agricultural and Pastoral Society had held its fourth exhibition at the North Dunedin Recreation Ground. However, few people were present since, he said, the entry fees were too high. This cost was too much “for the purpose of gazing at swine and bullocks when we can get access gratuitously to the Otago Council show”.[12]

Or “The hogs in the Provincial Council are still feeding on the public wash … Not a man of education in the midst of Otago’s representatives … Education is publicly ostracised by the wool-grower, cattle-rearer, clod-hopper, and storekeeper”.[13]

Copilot’s imagining of the Delphic Oracle, p. 70.

James Grant’s captivation with his provincial council representatives seems to be echoed by the assortment of strange-looking blokes in the visitors’ gallery. But why did the AI decide to exclude female guests? There is no way to find out since its internal ruminations evade explanation. So, I asked if AI is biased against women. It replied, guilty as charged; AI systems can exhibit gender bias, typically reflecting the historical biases in the data on which they have been trained.

Now What?

Above, we’ve noted how human creative workers are pushing back against AI. In addition, academics are getting interested in AI visuality, with, for example, Stanford University people looking at how spammers and scammers are producing images designed to increase the popularity of Facebook posts.[14] Then, it’s also becoming evident how AI is being employed in election periods to create fake imagery intended to deceive voters. Often, it’s far from clear as to who is behind the deepfake scams.[15]

Some maintain that AI has gone beyond just regurgitating and is capable of genuine creativity comparable to human artists. Further, in marketing, AI-generated imagery has been claimed to surpass human-made images in quality, realism, and aesthetics.[16]

Writers point out how we, as humans, typically shape our beliefs by sampling only a few facts among a huge range of possibilities that are available to us. However, AI systems are similarly and inevitably limited in the data they gather. Hence, thinking their outputs are the best available puts us at risk of incorporating their fabrications and bias into our knowledge base, thus further restricting our decision-making.[17]

AI is already writing somewhat predictable texts such as sports reports; presumably, the hazard is that journalistic downsizing will continue to result in story dumbsizing. Certainly, many fields of human expression will likely become more dependent on AI. If its outputs rely only on a circumscribed collection of texts and images, there’ll be a mind-numbing reductionism or circularity in what it produces, to the detriment of our collective knowledge and competence.

Some suggest that a key difference between human-created art and AI-generated visual images is that one can deliver authentic insights, while the AI version is artifice. Genuine art is said to help us to “think with the world, not about it.”[18]

More than that, it’s argued that artifice exists on a continuum between two extremes. At one end of the continuum sit advertising and pornography, images intended to create desire among viewers. Occupying the other end are propaganda and rhetoric, outputs designed “to inflame people’s emotions and to steer them towards acting or thinking or voting a certain way”.[19] Artifice as false art is said to bait a hook that will enable some (perhaps bad) actor to reel us in and then gain control of our emotions or behaviour.

The problem with this analysis is that none of the images we’ve been playing with in this post constitutes advertising, pornography, propaganda, or rhetoric. Indeed, the images are bizarre and comical, but no malevolent performer is pulling the strings. I’ll keep looking, but I haven’t yet found an account that works for me for how genuine art differs from AI outputs. As indicated above, some would argue that everything in these images consists of stolen property.

Yet, as the celebrated media theorist Neil Postman pointed out, any comprehensive new technology or media (such as AI) offers a Faustian bargain. Society gets to trade something of great value, perhaps its soul, for some worldly benefit. His perspective, of course, invites us to assess the deployment of AI through an ethical lens.[20]

Neil Postman image sourced from Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neil_Postman

If it’s true what they say, that AI visualisations will never be worse than they are right now, I’m not sure if we should celebrate their increasing sophistication or lament their likely loss of whimsy and caprice.

In any event, James Grant called himself a prophet in his own country, never honoured. But I’d like to think that if we’re looking for exemplars of complex and intriguing prose to expand our minds, we could do worse than take note of how he expressed himself (ideally avoiding being horsewhipped, as mentioned in the previous post).

I thank Dunedin Public Libraries for preserving and making available James Gordon Stuart Grant’s publications, including The Saturday Review and The Delphic Oracle.

Coming up in future posts:

After Some Debate, They Decided That Killing the Priest Would Probably Bring Bad Luck.

The Irish Spiritual Empire, a Cycle of Sectarian Epilepsy, and a Certain Fat Old German Woman.

Better at the Language Than Those Who Owned It and Equally Determined to be Both Themselves and to Conform, Fit In.

I Found It a Matter of No Small Difficulty to Collect the Bills Due by Females Who Have Been Assisted to the Colony.

Her Skirt Would Stand up Straight By Itself and Have to be Thawed Out.

His Wife Burst into Tears, Saying She Had Already Mortgaged Their Home so She Could Pay for Her Own Dredge Speculations.

An Irresistible Feeling of Solitude Overcame Me. There Was No Sound: Just a Depressing Silence.

Norman Conceded in His Mind that the Boomerang Would Crash Home Before He Could Snatch Out His Revolver.

The Sin of Cheapness: There Are Very Great Evils in Connection with the Dressmaking And Millinery Establishments.

The Poll Tax: One of the Most Mean, Most Paltry, and Most Scurvy Little Measures Ever Introduced.

Holy Wells: We are Order and Disorder.

God is Good and the Devil’s Not Bad Either, Thank God.

Notes

[1] Delphic Oracle, no. 1. p. 1.

[2] Cinque, Exploring the paradox, p. 215.

[3] Dubreuil, p. 36.

[4] Perth Comic Arts Festival.

[5] MacLeod, Why is AI being called ‘Boomer Art?’

[6] Merchant, The New Luddites.

[7] Timplalexi, Intermedial and theatrical perspectives, p. 164.

[8] Delphic Oracle, 22 April 1869, p. 60.

[9] Delphic Oracle, p. 221.

[10] Goulter, Sons of France, p. 154.

[11] Delphic Oracle, 8 March 1869, p. 53.

[12] Delphic Oracle, 14 January 1869, p. 39.

[13] Delphic Oracle, 1 June 1869, p. 70.

[14] DiResta & Goldstein, 2024.

[15] Swenson & Chan, 2024.

[16] Hartman, Exner & Domdey, 2024.

[17] Kidd & Birhane, 2023.

[18] Tartt, p. 14.

[19] Tartt, p. 12.

[20] Walters, Generative artificial intelligence, p. 122.

References

Cinque, Toija (2024). ‘Exploring the paradox: perceptions of AI in higher education – a study of hype and scandal’. Explorations in Media Ecology, Special Issue: Artificial Intelligence and Media Ecology, 23 no. 2, pp. 199-215.

DiResta, R. & Goldstein, J.A. (2024, March 18). ‘How spammers, scammers and creators leverage AI-generated images on Facebook for audience growth’. Stanford Internet Observatory. How Spammers, Scammers and Creators Leverage AI-Generated Images on Facebook for Audience Growth | FSI (stanford.edu))

Dubreuil, Laurent. (2024, July). ‘Metal machine music: Can AI think creatively? Can we?’ Harper’s Magazine, no. 2090, pp. 31-36.

Goulter, M.C. (1957). Sons of France: A forgotten influence on New Zealand history. Wellington: Whitcombe & Tombs.

Hartmann, Jochen, Exner, Yannick & Domdey, Samuel. (2024, April 10) ‘The power of generative marketing: Can generative AI create superhuman visual marketing content?’ Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4597899 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4597899

Kidd, Celeste & Birhane, Abeba. (2023). ‘How AI can distort human beliefs’. Science, 380 no. 6651, pp. 1222-1223.

MacLeod, Jim (2024, June 3). Why is AI being called ‘Boomer Art?’. LinkedIn, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/why-ai-being-called-boomer-art-jim-macleod-l029e/

Merchant, Brian. (2024, February 2). ‘The New Luddites Aren’t Backing Down’. The Atlantic, https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2024/02/new-luddites-ai-protest/677327/

‘Perth Comic Arts Festival Denounces Generative AI’ (2024, May 8) https://pcaf.org.au/ai-statement/

Swenson, A. & Chan, K. (2024, March 14). ‘Election disinformation takes a big leap with AI being used to deceive worldwide.’ AI-created election disinformation is deceiving the world | AP News)

Tartt, Donna. (2024, July). ‘Art and artifice’. Harper’s Magazine, no. 2090, pp. 11-14.

Timplalexi, Eleni & Rizopolous, Charalampos (2024). ‘Intermedial and theatrical perspectives of AI: Re-framing the Turing test’. Explorations in Media Ecology, Special Issue: Artificial Intelligence and Media Ecology, 23 no. 2, pp. 153-174.

Walters, Heather. (2024). ‘Generative artificial intelligence and the world Postman warned us about’. Explorations in Media Ecology, Special Issue: Artificial Intelligence and Media Ecology, 23 no. 2, pp. 121 -133.