His wife burst into tears, saying she had already mortgaged their home to pay for her own dredge speculations.

Previously: Her skirt would stand up straight and have to be thawed out.

This post investigates New Zealand’s Long Depression of the 1880s, how new systems of gold dredging renewed hope and prosperity in the colony, the era of steam technology, Dunedin as the world’s leading centre for dredge technology, a digger-friendly government that privileged the expansion of gold dredging over environmental protection, the bust that followed the boom, and Dunedin settling into a state of sinners’ remorse.

In these posts, I tell of two of my ancestors who, in 1861, arrived in Aotearoa New Zealand. My Irish great-great-grandmother Maria Dillon landed in January, just a few months before the gold rush that would utterly transform Dunedin and the province of Otago. My great-grandfather, the Scotsman Archie Sligo, was among the flood of hopeful diggers who disembarked in October of that year. I wanted to learn more about the forces that propelled them from their homelands, what attracted them to their new country, what happened here shortly before they arrived, and what they encountered as they set about making new lives for themselves. These posts reveal part of their stories.

By the late 1870s, the cold winds of change were playing through the colony of Aotearoa New Zealand. The abrupt failure of the City of Glasgow Bank in 1878 was a shock not just to its 1200 shareholders in the UK and the colonies, many of whom went bankrupt, but also to those who hadn’t experienced a bank collapse before and who assumed that banks didn’t fall over.

At the time, bankers would like to represent themselves as the most ethical businesspeople in the community, so people were appalled by revelations both of how much deceit the bank’s managers had practised in refusing to reveal the company’s actual situation and their bad decisions in lending money to speculators in New Zealand and Australia. This was one of the early indicators that marked the start of New Zealand’s long-enduring depression of the 1880s.

City of Glasgow Bank Cheque, 1877, a year before its collapse. Photographer AllyD, 2014. City of Glasgow Bank Cheque

By that point in Otago, the former boom times of the 1860s seemed to have ended permanently. The colonists’ sense of potential to become a Better Britain withered as departures outweighed migration to Aotearoa. As the decade of the 1880s began, things were at an impasse – how to rebuild optimism, achieve security, and generate wealth?

While the Long Depression of the 1880s ground on, Otago’s economy suffered; gold was no longer engendering prosperity, and then, given the extent of decline now occurring overseas as well, buyers for Otago’s wool and grain crops reduced their offers. Farmers found the plagues of rabbits had outrun their control, and farming practices ill-suited to Otago’s terrain, such as annually burning off tussock, were accelerating the erosion of hillsides. Many contemplated moving across the Tasman, where Victoria was still doing well, and a recession would not inflict that state until the 1890s.[1]

Yet the diggers still knew that much gold remained. From the 1860s, miners had worked as deep as they dared in fast-flowing waters to win the metal, often at severe risk to their lives. Should their river ever drop, the auriferous quality of the Otago beaches and terraces demonstrated that gold in volume was just a few metres from the miners’ grasp if anyone could calculate how to extract it.

Shotover River at Shotover Canyon, Arthur’s Point, Central Otago, 2014. Photographer Pseudopanax. Shotover River

Yet these deep, narrow-channelled rivers were perilous to life and, even when not in flood, had claimed many miners, squatters and others who had set out to cross them with insufficient respect for their power. Among the “if-only” speculations was the wish to somehow divert their flow to win the gold. But virtually always, their sheer volume of water had made this impossible.

The Otago rivers were among the most challenging anywhere in the world. The terrain’s steep alpine character and deep-piled snow that engorged them combined to create an exceptionally demanding training school for diggers. The swift-streamed and variable Clutha and Kawarau, in particular, featured flooding in spring, freezing in winter, and submerged drifts of gravel impelled along by the water’s power.

The European miners had done their best using the technology of the time, while the Chinese diggers who followed them were more systematic and also prospered. Once the easy-to-find alluvial gold was no more, miners’ attention turned to more scientific and mechanised means of mining quartz for its gold content, then to ways to dredge river-buried deposits. By the time of the dredging boom of the 1890s, all were sure that an El Dorado was certainly and tantalisingly near at hand, still buried under Central Otago’s swift-running waterways.

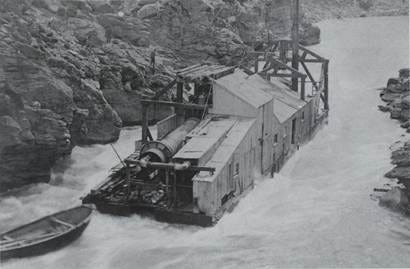

The first dredging attempts comprised simple pontoons or two boats linked by a platform, fitted with a hand winch and a long lever of wood and iron, a spoon device with a rawhide bag at its end. These spoon dredges were operated by one man pressing the spoon into the riverbed while his friends dragged it along by the winch.[2]

However, this method of extraction was slow and primitive. The next stage of technology was the “current wheeler”, designed to harness the river’s volume. These were dredges with a giant water wheel attached, employing the river’s force to work a system of buckets that yielded a continuous flow of potentially gold-bearing metal.[3] By the early 1870s, the current wheeler had largely superseded the spoon dredge, and by 1880, a good income came from wheelers dredging as deep as six metres.[4]

Dunedin Gold Dredge, 1870-1880s, Otago, photographers Burton Brothers. Te Papa (O.026529) The Dunedin was 20 metres long and 8 metres wide, featuring new technology, such as adding an iron tooth to every third or fourth bucket to serve as a pick when it hit the bottom.[5]

The newspapers started getting on board, with excited references to Otago’s rivers as a new Pactolus. That was the site where the mythical King Midas came to bathe, turning everything he touched, including all the rocks and sands, into gold. However, neither the media nor the population at large had yet comprehended the message implicit in the story, that you should be careful what you wish for.

More profitable outcomes were to come from the era of steam technology, with larger and more powerful dredges.[6] These employed mechanisms that broke through the hard, cement bases of the river, permitting the dredge’s buckets to plunder the rich gold-bearing metal beneath.

By the late 1880s, technological improvements resulted in dredges massive enough to cope with the deep, rapid-flowing rivers. The larger the dredge, the greater the need for its promoters to seek capital funding and the greater the temptation to exaggerate the potential financial returns. Excitement grew when Choie Sew Hoy, a Dunedin businessman and his partners dredging on the Shotover started by July 1889 to win substantial quantities of gold. While most in the community still regarded dredging as unproven and risky, cheerleaders for the industry pointed to their success as an example of how profitable a dredge could be.[7]

Sew Hoy’s Big Beach Claim Historic Area, 2022. Photographer Sgroey. Sew Hoy Claim

Yet in 1889, there were still plenty of sceptics, such as the Otago Daily Times’s columnist Civis: “There is madness in the air. Every day sees a new company launched; shares in companies that have not yet paid a dividend are every day rising, rising, rising. This is the hot fit; the cold fit will follow in due course … bless every mining share, through Otago’s wide expanse; for never a beggar need now despair, and every rogue has a chance.”[8]

However, other ventures did not deliver the early promise of dredges such as Choie Sew Hoy’s, and an early 1889 strain of community gold fever soon faded.

Investigations were continuing though into how to improve the technology of the new, steam-powered dredges in ways that would enable them to cope with the complexities of Otago’s narrow-channelled and rocky rivers with what could be vast floods when the snow in the mountains above melted. Over several years, mining engineers were building consensus about how to standardise dredge design and ways to improve dredging operations.[9]

By the mid and late 1890s, steam dredges could gouge deeper than anything before them. They hauled up unprecedented and sensational quantities of gold, though at the cost of creating vast, unsightly volumes of rocks and debris alongside the rivers.

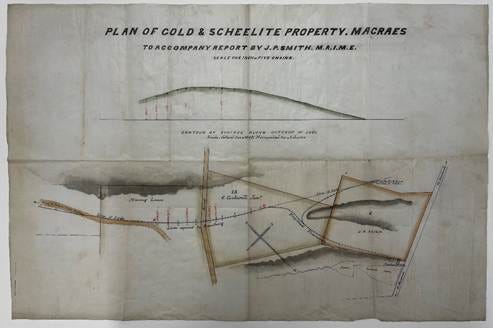

Macrae’s Flat Plan. Photograph by the author, 2024. Collection of Sligo Bros papers, Hocken Library, Otago University, Dunedin.

Local farm owners and leaseholders became infuriated at the dredgers who would silt up the rivers, casually carve inroads into their agricultural land and dump huge piles of tailings waste onto their property. But their complaints to the regional authorities found little sympathy. Public sentiment was distressed at still being in the grip of a severe depression. People started to obsess about the prospects of windfall gains and an imagined return to the sudden wealth achieved by some in their parents’ generation. Minds reverted to the good old days, how, between 1861 and 1865, gold mining, most of it in Otago, had accounted for over 65 per cent of New Zealand’s export earnings.[10]

Part of the attraction, too, was that whereas the original rush of a generation earlier had required people to undertake literally the hard yards of actually digging in highly challenging climactic conditions, now anyone who could raise or borrow the money or just promise to pay could share in the rush to affluence.

Hence, landowners gained minimal traction for their complaints and had little comeback. While the Gold Fields Amendment Act of 1875, amending an earlier 1866 act, had stated that compensation to landowners on account of mining damage could be ascertained by arbitration, in practice, the new law favoured the interests of the gold hunters.

Brooking points out that New Zealand miners “received many more concessions in their use of precious water resources than did miners in either California or Victoria. As a result, they made comparatively more mess and fouled New Zealand rivers on a much grander scale than in more arid countries, despite our rush being a relatively small rush by world standards”.[11] New Zealand could have required its miners to stack their tailings or build debris dams, as in Australia, but they responded that they could not afford to do so, and the digger-friendly government was inclined to agree.[12]

Tailings From Early Alluvial Gold Mining, Quartz Reef Point, Central Otago, 2011. Photographer TheKiwiAbroad. Tailings

However, Moore suggested that while undoubtedly there was a high environmental cost from the dredging boom, long-lasting economic benefits resulted, especially for the enduring surge it engendered for local industry in Central Otago. Since the 1870s, local citizens had been complaining about how progress in pushing the promised railway into the district had stalled, but from the inception of large-scale dredging from around 1890 onwards, it became easier for locals to make a case for completion of the rail system into Central Otago.[13] Once rail was in place, commercial fruit growing and farming more generally garnered substantial benefits.[14]

The debate about the community’s ecological responsibilities continues to the present day. Yet, there is a long history of unresolved tension between collective benefits and landowners’ preference to do whatever they want. In 1871, Dunedin’s Evening Star pointed out how diggers “are now engaged in sluicing away thousands of acres of fine rich soil, which is washed down by our rivers, converting them into muddy streams, unfit for the habitation of fish; and through the raising of their beds, rendering wide tracts of country liable to destructive floods” so that the sluicer … “leaves a bare and useless rock.”[15]

Sluicing For Gold, 1920s, New Zealand, Photographer unknown. Te Papa (O.020570) Sluicing For Gold

Public concern at mining damage emerged in the media: some pointed out how sluicing, in particular, was a highly haphazard way of getting gold, perhaps burying as much undiscovered treasure permanently under tailings as ever extracted. One commentator remarked how the diggers’ work had resulted in trees alongside riverbeds buried so “the upper branches now raised their skinny fingers, like Macbeth’s witches, against the outrage done to Nature. At Waikaia, fertile alluvial flats have been submerged under 40 feet of sludge and made useless forever”.[16]

Waikaia Dredging Field. Photograph by the author, 2024. Collection of Sligo Bros papers, Hocken Library, Otago University, Dunedin.

However, New Zealand’s 1880s Long Depression drifted into the 1890s, and the community debated the extent of the environmental damage it would accept for winning some much-needed wealth from the ground.

The industry explodes

In the last years of the nineteenth century, Otago-based mining entrepreneurs built and operated a series of dredges on the Shotover and the Kawarau. They discovered a first-mover advantage, quickly earning a good return on investment, so that by 1898, seventy-four dredges were upon Otago rivers, with most attention paid to the Clutha. Exponential growth occurred, with 162 dredges operating by 1899, and at the turn of the century, there were 187. This would be the peak of the dredging boom. The industry had proven what the diggers of the 1860s had suspected and, as described in earlier posts, what Māori in pre-European times also knew, that the Mata-Au / Clutha had to be one of the most abundant gold-bearing rivers in the world.[17]

Otago Dredge, Millers Flat, Clutha River, circa 1900, New Zealand, photographers Muir & Moodie. Te Papa (C.016236) Otago Dredge

By the turn of the century, Otago had over 30 years of experience designing and operating gold dredges. Since 1890, the industry had surged, leveraging on its learning the hard way of the problems inherent in Otago’s complex and exceptionally challenging terrain.

Accordingly, at the turn of the century, Dunedin was the predominant centre in the world for dredging expertise. Many international visitors arrived to learn “what they could of this new dredging industry, described by one Canadian visitor as the Mecca to which the engineer in search of information on the subject directs his pilgrimage.”[18] They arrived wishing to recruit mining specialists from Otago and to copy locally invented dredges for South America, Siberia and elsewhere.[19]

The rugged Otago terrain had created a population of dredge miners with exceptional capabilities, in Sinclair’s words:

The careless ease with which the dredgemen of last century moved their cumbersome craft up and down the rock-strewn river is almost incredible, even in this later mechanical age, when modern eyes can view in comfort the obstacles and difficulties which such operations must have presented.[20]

Assembled here was perhaps the world’s largest-ever dredging fleet, and the lure of a new, mechanised gold rush dangled in front of the populace, so much in harmony with the wonderment that many felt at how new Victorian technology, such as steam power and electricity, was transforming their lives.[21] But the Presbyterian Free Church’s dour dictates against the perils of gambling and immoderate and unseemly behaviour evaporated like mist on the Dunedin harbour as though they had never been.

As soon as it became public knowledge that the bed of the Clutha/ Mata-Au was almost certainly replete with gold and that only the new technology of steam-powered dredging could liberate this treasure, Dunedin and the entire province had a collective rush of blood to the head. Previously reputable citizens, whose religion was most censorious of gambling, set about raising cash in any way possible, including borrowing from anyone who would lend and mortgaging their houses to purchase new dredging shares.[22]

Roxburgh Dredge, 1870-1880s, Kawarau River, photographers Burton Brothers. Te Papa (O.026515) Roxburgh Dredge

In Patterson’s view, “some Scottish colonial businessmen enthusiastically espoused the boom and bust mentality,” which somehow was balanced with their Calvinistic conservatism.[23] So rather in contrast to what is often regarded as Scottish business people’s caution, demonstrating their claim to be canny Scots, at times of the surge in dredging, many were seduced by the possibility of quick riches (coupled with distress at the fear of missing out), people now taking shortcuts in their investment practices.

In contrast to more settled conditions in the UK, new colonies, such as Aotearoa New Zealand, were perceived as possessing unique opportunities that opened themselves up for risk-takers. Belich suggested that for businesspeople of the time, “the trick was to achieve take-off, to achieve long-term viability, by exploiting a particular spasm of progress-boosted opportunity. You might then change horses from extractive, finite, rush-phase activity to sustainable, settled, ongoing activity.”[24] The issues were, though, to accurately discern when a genuine opportunity was presenting itself, as opposed to a false and delusional dream based on minimal evidence, and next, how to figure out if a new form of business was sustainable.

In November 1899, over 200 applications for dredging licenses were waiting to be dealt with in the Otago courts, while by the end of that year, 171 dredging companies were registered. At one point, over 200 dredges were operating in Otago. Yet despite a few dredges winning spectacular returns, most did not generate anything like the income their investors had dreamed of.[25]

Gold Queen, Roxburgh, New Zealand, photographers Muir & Moodie. Te Papa (C.016134) Gold Queen

Enter the financier

However, dredging involved more than just the science and arts of the mining engineer. Just as important were the organisational capabilities needed to obtain finance for the capital-hungry nature of dredge mining. A dredging boom exposed how few people had relevant experience and, therefore, who had credibility with British venture capitalists lured by the possibility of winning attractive returns. Many skilled miners and ex-miners with a business bent started seeing the benefits of leveraging their experience to become professionals in raising finance for mining ventures.

The sudden onset of the dredging boom late in the century opened for Willie, Archie and Jessie’s son, now in the latter part of his 30s, a new possibility to engage in the more exciting occupation of his earlier gold mining years. Gold dredging would call upon the proficiencies Willie had hard learned – knowledge of geology, underground mining expertise, and the ability to raise investor funding. Willie could see opportunities for his skills and experience.

Dunedin Exchange Building, circa 1890s. Photographer unknown. Dunedin Exchange Building

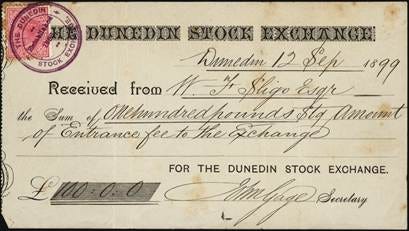

Before 1866, stockbrokers were part-timers, but the rushes of the 1860s made it feasible for full-time brokers to make a living. The first stock exchange in Aotearoa was the Dunedin Brokers’ Association, comprising 12 people who met to trade in mining and other stocks. Membership cost £25.

Those aspiring to become association members were voted upon by existing brokers, who would put a white or black ball into a ballot box. The applicant was admitted if he (all were men) scored a two-thirds majority of votes and subsequently passed inspection on the grounds of morality (perhaps reputation) and sufficient personal funds.[26] From this came the term blackballing.

However, the passion for buying into dredging companies in the early 1890s led the association to raise its membership prices to £100. In 1893, the association renamed itself the Dunedin Stock Exchange, while many part-time brokers launched their own businesses to capitalise on what was turning into everyday citizens’ rising dread of missing out.

The growing public hunger to purchase shares in prospective dredging companies generated two further exchanges, the Equitable Exchange and the Otago Exchange. Both would fold when the dredging bubble burst at the start of the new century.

In early September 1899, Willie Sligo and his younger brother James were among a group of applicants seeking licences to practise as members of the Dunedin Stock Exchange. The sense of transitioning from one mining era to another was acute for Willie and his siblings. They knew that their father, Archie, laid up in the family home in Filleul St, had only days to live. They watched him gradually succumbing to the assault of silicosis, then known as “phthisis”, or the miner’s disease. This affliction was also known as consumption, along with other wasting diseases, since it seemed to consume the person.

As well as the miner’s disease, this is the quarryman’s. Here, fine silica dust particles collect over time in the lungs. Ultimately, the lungs cannot clear themselves by mucous or coughing, with consequent shortness of breath, wasting of the lungs, and death by asphyxiation. Silicosis is one of the oldest occupational diseases, is incurable, and worldwide still kills thousands yearly.[27]

On 10 September 1899, the day of Archie’s death, Willie and James received letters confirming their acceptance to the Exchange. The family buried Archie on 13 September. His children acknowledged the loss of this man from whom they had learned so much about mining. Archie’s experience had begun with his work in the Scottish coal mines and had culminated in almost 50 years as a digger in Australia and New Zealand.

Willie and James were the last to pay the lower sum of £100 per licence. New licences immediately after that cost £250 in response to the surging demand for Exchange membership, but towards the end of 1899, the entry fee shot up further to £600 per seat as the boom reached its crescendo.[28]

This was September 1899: Willie and James had just over half a year of prosperous times to come before, in April 1900, dredging mania started to lurch into something like alcoholic remorse and then evaporate into a terminal slump. Share prices would bottom out, most dredging companies collapsed either fast or slowly, and it became exceedingly difficult to find anyone willing to gamble further on the future of dredging in Otago.

Meanwhile, Otago still featured much entrepreneurial activity. By 1899, 162 dredges lay “like giant prehistoric monsters upon the rivers and mud flats of Otago”, churning their way throughout Otago, with 187 in the following year. Windfall profits resulted for some of them.[29]

Yet, within about three years, most of these companies would fail.[30] Winning river gold required skill, experience, and luck. The work was hazardous, with what 21st-century observers would see as a nonchalant attitude to health and safety. The uptick in the number of dredges outstripped the skills available, so that competent, let alone qualified, dredge masters who knew how to get the best out of their machines were few.

Competent labour was scarce and, therefore, expensive. Dredge masters complained that, too often, workmen reported for duty inebriated. This reinforced the old saying that the principal causes of death in New Zealand were drink, drowning, and drowning while drunk.

You might say that Willie was at the birth of postmodernity as he and James started to make a living via the growing knowledge economy, working in the intangible realm of advisory services on mining stocks and shares, buying and selling shares in existing or proposed companies.

However, seeing how boom can instantly bust and realising that something concrete had to supplement their role as sharebrokers, Willie and James established themselves as vendors of mining and other related equipment and machinery in machinery sales. Both these elements were founded on their hard-rock gold reef mining and dredge mining expertise.

This synthesis of mining engineer and sharebroker is illustrated by two linked advertisements, employing the restrained tone then required, in The Otago Witness, dated 17 August 1904, five years after the brothers had established their partnership.

The gold-dredging boom did foster the building and engineering trades as they set about meeting the demand for new dredges. By March 1900, Otago’s dredging companies had a combined capital value of around £2.5 million. While the collapse of the dredging boom would eventually gut the engineering industry, the building trades continued to thrive in response to an increased demand for better quality and larger houses.[31]

Hartley & Riley

One of the most enduring and famous of all dredges was the Hartley & Riley, named after Horatio Hartley and Christopher Reilly, an American and an Irishman who were the first to uncover substantial quantities of gold in the Clutha/ Mata-au back in 1862. Their discovery led to a cascading revelation of new watery fields on the Cardrona, the Arrow, the Shotover, and beyond. It was as though invoking their names for the dredge was a kind of magical thinking, as if their luck and capability would recur thirty years onward for a new generation of aspiring miners. Other examples of naming strategies designed to encourage local optimists to part with their cash included Golden River, Golden Gravel, Golden Reward, Golden Banner and Golden Chain.[32]

The Hartley & Riley dredge, perhaps more than any other, would capture the public imagination, generating vast excitement around its potential as it dramatically transitioned from scanty to massive returns, literally overnight.

Construction of the Hartley & Riley Dredge next to the Clutha in the Cromwell Gorge, 1890s. Photographer Burton Brothers. Te Papa Collections. Construction of Hartley & Riley Dredge

The story goes that the operator in charge took over his midnight graveyard shift in a somewhat impaired state after a drinking session. Lacking control over the equipment, he let the apparatus of buckets drop hard into the river. It smashed through the cement base of the riverbed, and the buckets drove deep into thick deposits of gold.[33]

Stories about buried wealth and enormous dividends for investors infected Dunedin’s citizens with a new strain of fever. The capital needed for new dredges came mainly from existing dredging profits acquired from successful companies. Yet dredges were not straightforward to relocate once the stretch of river they were on had been comprehensively worked. Usually, it was impossible to tell in advance which dredges would or would not generate income or how long their profit-taking would last.

Such uncertainty did not deter everyday people from putting their last pound into new dredging ventures or even borrowing heavily to buy dredging shares. Many dredging projects were dangerously speculative and possessed only minimal evidence that gold was actually in the tract of the river the mining company had secured.

In some instances, promotional materials were designed to deceive, and accusations emerged that gold fragments had been planted on the site. Some companies failed even before their dredge had begun working, through deficient mining or engineering knowledge or shareholders panicking and withdrawing their capital.

Many investors did not want to learn how dredging operated or to remain a share-owner long-term. Much more frequent was to buy shares either using existing funds or, commonly, with no funds, to sell them when their value shot up, thus permitting the punter to pay their dues to the broker and, ideally, make a substantial profit.[34]

As ever, the craze for dredging shares meant that relatively few prospered and many lost out. Immediately following its first significant success, shares in Hartley & Riley leapt from ₤1 to over ₤26.[35] The Hartley & Riley record for one week in 1900 was a return of 1187 ounces of gold, currently valued at over US$3.9 million.[36]

The Hartley & Riley Dredge, Clutha, 1899. The image is reproduced courtesy of Central Stories Museum & Art Gallery, Alexandra.

But the chief engineer of Hartley & Riley, just before relocating from a most profitable part of the river, sold off a substantial parcel of shares that he owned at top price, then promptly resigned from his job and left the district. He knew that the company’s share price would immediately slump in parallel with the volume of gold it was now likely to win. He also had no wish for people to recognise him on the streets of Dunedin.[37]

The story was told of one man who had contracted to purchase dredging shares but could not produce the money when required to pay up. Knowing he was about to face financial ruin, he went to his wife, the owner of the family home, begging her to raise a mortgage on the house to permit him to pay his debts. His wife burst into tears, saying she had already mortgaged their house to pay for her own dredge speculations.[38]

By midway in the year 1900, the boom had ruptured. Companies beseeched their shareholders for more investment in the hope that they might yet make a profit, but by this point, no one wanted to let good money chase bad. A chain of company liquidations proceeded from 1900 onward, with collapses occurring from valueless stretches of river, initial under-capitalisation, inability to obtain ongoing finance, inadequate technology, inept management, incompetent or reckless boards of directors, and deliberate fraud.

Nature showed herself disinclined to cooperate, too, and Central Otago’s harsh milieu displayed what it could do. A massive flood swamped the Clutha in October 1901, destroying one dredge, and further accentuating local pessimism.[39]

Newly ruined investors held sharebrokers’ inadequacies and deceits accountable for the industry’s failure. Hearn and Hargreaves thought that some brokers were perfectly responsible and ethical people who did not intend to deceive. Others were undoubtedly cheating the gullible, while still others were as taken aback at what had transpired as other citizens.

By 1891, when the full impact of the bust was evident, much condemnation occurred of those “horse-leeches known as mining companies, with their secretaries, engineers, managers, etc., and last, but not least, the promoters who live and grow fat on the gullibility of human nature… I have been in Dunedin for many years, and during my experience I have never found it in the same depressed condition as at present.”[40]

A glum mood of sinners’ remorse settled upon the people, now as pessimistic about dredging as they had ever been optimistic about its prospects. Dunedin failed to grow as its boosters had so devoutly hoped, and by 1911, Dunedin had lapsed to being the smallest of the four main centres.[41]

The Hartley & Riley company achieved an unusual longevity of 16 years, wound up in 1913, and Willie’s younger brother, James, his partner in Sligo Bros., served as company liquidator.[42]

This plaque came into the possession of Sligo Bros. as company liquidators and was held in the family until donated by Louise Sligo, Whanganui, to the Central Stories Museum & Art Gallery, Alexandra. Photo by the author and image reproduced courtesy of the Museum.

Despite the wealth that dredging delivered, its economic contribution was considered limited, with some arguing that the industry never achieved its potential. In one of his commentaries in The Otago Daily Times on dredging in the Clutha, Willie explained how:

One huge bungle prevailed from first to last, and no effort was made to remedy it. That was the undersized, inefficient dredges. No matter how heavy the ground, one would find the same old 4 ½ cubic feet bucket; the same 12 h.p. [horsepower] engine and 16 h.p. boiler or a 16 h.p. engine and 20 h.p. boiler. We know now that the majority of companies started with far too little working capital. The engineer was usually instructed to design a dredge within the limits of the company’s finance. If machines of half the strength and power of the American Rimu Flat dredge operating on the West Coast had been erected there would have been an agreeable story to relate. Undoubtedly there are large quantities of gold in many of the claims that had to be abandoned because the dredges on many parts of the river were not capable of doing the work required of them.[43]

Within 30 years, dredging technology had improved, and Willie detailed how “a very hard revolving cutter is now fitted on the end of the suction pipe. It serves the double purpose of breaking up the bottom and causing sufficient disturbance to enable the suction to lift the gold from the bottom”.

By the 1890s, Willie’s mother Jessie had lost her sight, as reported in her fifth son Norman’s story of his time as a miner in Western Australia, Mates and Gold, which I address in a forthcoming post. Jessie lived until 1901, surviving Archie by just two years, dying of influenza and heart failure. Jessie and Archie are buried, along with their son James (who died in October 1922), in the Presbyterian section of Dunedin’s Northern Cemetery.

Coming up:

An Irresistible Feeling of Solitude Overcame Me. There Was No Sound: Just a Depressing Silence.

Norman Conceded in His Mind that the Boomerang Would Crash Home Before He Could Snatch Out His Revolver.

The Sin of Cheapness: There Are Very Great Evils in Connection with the Dressmaking And Millinery Establishments.

The Poll Tax: One of the Most Mean, Most Paltry, and Most Scurvy Little Measures Ever Introduced.

Holy Wells: We are Order and Disorder.

God is Good and the Devil’s Not Bad Either, Thank God.

Notes

[1] Sutch; Olssen, pp. 90-91.

[2] Gilkison, p. 150.

[3] Sinclair, p. 14.

[4] Hearn & Hargreaves, pp. 7-8

[5] Hearn & Hargreaves, p. 9.

[6] Moore, p. 40.

[7] Hearn & Hargreaves, p. 12.

[8] Civis, ODT, 5 October 1889.

[9] Hearn & Hargreaves, p. 22.

[10] Hearn, p. 84.

[11] Brooking, p. 22.

[12] Hearn, p. 86.

[13] Belich, p. 370.

[14] Moore, p. 46.

[15] Hearn & Hargreaves, p. 68.

[16] Mining: The tailings question. Otago Witness, 8 Sept 1892, p. 14.

[17] McLintock, p. 672.

[18] Hall-Jones, p. 173.

[19] Sinclair, p. 123.

[20] Sinclair, p. 34.

[21] Hearn & Hargreaves p. 75.

[22] McLintock, p. 671.

[23] Patterson et al., p. 98.

[24] Belich p. 376.

[25] Murray, p. 55.

[26] Grant, First stock exchanges, Te Ara, 2010. https://teara.govt.nz/en/stock-market/page-1)

[27] Occupational health: Silicosis, 2023.

[28] Grant, First stock exchanges, Te Ara, 2010. https://teara.govt.nz/en/stock-market/page-2

[29] Field & Olssen p. 53; Sinclair, 1962, p. 50.

[30] Sinclair, 1962, p. 125.

[31] Olssen, Building the new world, p. 99.

[32] Hearn & Hargreaves, p. 32.

[33] Gilkison, p. 154.

[34] Hearn & Hargreaves, p. 32.

[35] Gilkison, p. 155.

[36] Sinclair, p. 135.

[37] Gilkison, p. 156.

[38] Gilkison, p. 157.

[39] Hearn & Hargreaves pp. 43, 51.

[40] Mining companies, ODT, 6 October 1891.

[41] Hearn & Hargreaves, pp. 76, 78.

[42] Gilkison p. 135.

[43] Sligo, 1924.

References

Belich, J. (1996). Making peoples: A history of the New Zealanders. The Penguin Press.

Brooking, T. (2011). ‘Gold in Otago: Digging for a new perspective’. In A golden opportunity: Proceedings of the New Zealand Society of Genealogists Annual Conference. R. Stedman (Ed.). The Society, pp. 17-22.

Civis (1889, 5 October). Supplement: Passing notes. Otago Daily Times, p. 5.

Gilkison, R. (1958). Early days in Central Otago. 3rd ed. Whitcombe & Tombs.

Grant, D. (2010). First stock exchanges, Te Ara. https://teara.govt.nz/en/stock-market/page-1

Grant, D. (2010). First stock exchanges, Te Ara. https://teara.govt.nz/en/stock-market/page-2

Hall-Jones, J. (2005). Goldfields of Otago; An illustrated history. Craig Printing.

Hearn, T. (2002). ‘Mining the quarry’. In Eric Pawson & Tom Brooking (Eds.). Environmental histories of New Zealand, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, pp. 84-99.

Hearn, T.J. & R.P. Hargreaves (1985). The speculators’ dream: Gold dredging in southern New Zealand. Allied Press.

McLintock, A.H. (1949). The history of Otago: The origins and growth of a Wakefield class settlement. Whitcomb & Tombs.

Mining companies: To the editor. (1891, 6 October). Otago Daily Times, p. 4.

Mining: The tailings question. (1892, 8 September). Otago Witness, p. 14.

Moore, C.W.S. (1953). The Dunstan: A history of the Alexandra-Clyde district. Whitcombe & Tombs.

Murray, J.S. & RW (1977). Costly gold: Clutha riches and their human toll. AH & A.W. Reed.

Occupational health: Silicosis. (2023). International Labour Organization. https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/safety-and-health-at-work/areasofwork/occupational-health/WCMS_108566/lang--en/index.htm

Olssen, E. (1995). Building the new world: Work, politics, and society in Caversham, 1880s-1920s. Auckland University Press.

Olssen, E. (1984). A history of Otago. John McIndoe.

Patterson, B., Brooking, T. & McAloon, J. with Lenihan, R. & Bueltmann, T. (2013). Unpacking the kists: The Scots in New Zealand. McGill-Queen’s University Press & Otago University Press.

Sinclair, R.S.M. (1962). Kawarau gold. Whitcombe & Tombs.

Sligo, WF (1924, 16 December). Gold mining in Otago: The application of new methods. Otago Daily Times, p. 2.

Sutch, W.B. (1966). The quest for security in New Zealand 1840 to 1966. Oxford University Press.