An Irresistible Feeling of Solitude Overcame Me. There Was No Sound: Just a Depressing Silence.

Previously: His Wife Burst into Tears, Saying She Had Already Mortgaged Their Home to Pay for Her Own Dredging Speculations.

We explore goldmining in Central Otago mountains, the challenges of life in Macetown, the evolution of a new Pākehā colonial society, the growth of a sense of egalitarianism fostered by a commonly shared belief system, the mushrooming of athenaeums and libraries, the foundation of newspapers, and reading for leisure and pleasure rather than for moral enlightenment.

In these posts, I tell of two of my ancestors who, in 1861, arrived in Aotearoa New Zealand. My Irish great-great-grandmother Maria Dillon landed in January, just a few months before the gold rush that would utterly transform Dunedin and the province of Otago. My great-grandfather, the Scotsman Archie Sligo, was among the flood of hopeful diggers who disembarked in October of that year. I wanted to learn more about the forces that propelled them from their homelands, what attracted them to their new country, what happened here shortly before they arrived, and what they encountered as they set about making new lives for themselves. These posts reveal part of their stories.

In his History of Goldmining in New Zealand, Salmon described the exceptional difficulties of functioning in Central Otago’s mountainous terrain. He narrated the attempt by the Sunrise Company of Macetown “to work the reef on Advance Peak at a height of 5,600 ft, where the head of the shaft was surrounded with deep snowdrifts for six months in the year,” calling it the country’s highest altitude mine.[1]

Central Otago, N.Z. Photographer Phillip Capper, 2005. Central Otago

Archie and Jessie’s third son Willie, my grandfather, was one of this group, and in the third of his reminiscences on his mining experience in Macetown in The Otago Daily Times, he described how:

A small party, including … the writer, wintered it there, and a very severe three months were experienced. We put up snow poles from the camp to the mine. On one occasion the snow drifted over the tunnel mouth, and when the relieving men came along in the morning they had some difficulty in clearing the snow away and locating the tunnel mouth. We got up a supply of provisions before the winter set in. Shortly afterwards the whole creek and surroundings from Macetown up were ice-bound. The mountain streams gradually froze up and formed huge icicles over the cliffs of rock. These gradually spread and joined up into masses of perpendicular ice. At the end of ten weeks a ray of sun shot over Advance Peak, and a fortnight later we were in touch with the outer world.[2]

Sunrise near Queenstown, Central Otago. Photographer scott1346, 2019. Sunrise near Queenstown

Transitions from miner and mining engineer to other occupations were also precipitated by the decline in quartz mining in Otago at the end of the century. Hall-Jones, in his Goldfields of Otago, explained how “The ore [from the reef on Advance Peak] was conveyed down to the Premier battery for crushing, but with high operating costs and exposed working conditions on the bleak mountainside, most of the mines soon closed down.”[3]

Salmon reports of the Macetown mines:

The Sunrise Mine was closed in 1899, followed by the Tipperary in 1901, and finally by the Premier, in 1906. The settlement [Macetown] was abandoned. The books were left in the deserted schoolroom, and outside the daffodils continued to bloom beside the silent machinery.[4]

As Salmon states, the Sunrise mine closed in 1899, prompting Willie, among other shareholders, to look for other jobs, and as its output tapered off, Willie found work in the Dunedin railways. But 1899 also marked the peak of Otago’s gold dredging boom, and as reported in the previous post, it was the year in which Willie and his younger brother James, also successful in his mining ventures in Aotearoa and Western Australia, were accepted for membership in the Dunedin Stock Exchange.

Eileen Beaton reports that Alex, the eldest of Archie and Jessie’s children, was similarly active in Macetown. Along with William Cox, he attempted to block the Arrow River on the north side of Advance Peak to divert its flow so that the old riverbed could be more thoroughly prospected. Alex’s brother in Dunedin was their agent, presumably involved in raising capital for this endeavour. This would have been either Willie or James Sligo undertaking such an audacious and speculative engineering venture.[5]

Foggy Mountainscape, Otago. Photographer Scott Greer, 2016. Foggy Mountainscape, Otago

The prolific journalist and regional historian Frederick Miller, author of Golden Days of Lake County, commented of Willie that he:

knew more than any man living about the remote little mining centre of Macetown. It was from articles written by him years before that I obtained much of the information for my chapter on Macetown in … Golden Days of Lake County.[6]

The miners knew that much gold was to be retrieved from the hills that loomed over you as you walked or rode your horse up the Arrow River’s narrow gorge, but the landscape’s precipitous nature posed challenges that no miner ever had to encounter in their previous lives on the Victorian goldfields. Hacking a trail through challenging terrain was slow and frustrating, especially in winter when Macetown’s tiny settlement became isolated by snowdrift, and the Arrow froze. Miners dug tracks for riders and their packhorses into the sides of the gorge, but even so, the trail’s steepness caused endless problems. They created new and safer horseshoes, such as hammering pointed frost nails into them, giving horses a chance of not slipping.

Even so, accidents were frequent, and some deaths occurred from falling. By 1880, Macetown’s residents were sick of their virtual isolation over winter and petitioned for a road to accommodate a horse and cart. It took until 1884 for the 15-kilometre winding trail to be constructed up the Arrow River valley, though with 23 river crossings en route.[7]

Lake Wakatipu, Central Otago. Photographer Bernard Spragg, 2020. Lake Wakatipu

Willie wrote about the emotional impact of extended periods working in isolation in his third reminiscence written for The Otago Daily Times on a return visit to Macetown:

Towards evening an irresistible feeling of solitude overcame me. The high mountain peaks stood out in the dim light like giant sentinels. There was no sound: just a depressing silence. Here and there were abandoned camps, and away on the mountain sides were others not visible, but I knew the direction, for I had long ago been round them all, and the question forced itself on me, “Where are the boys of the old brigade?”

Some I knew had crossed the divide; others, independent old chaps, moved down the river and eked out an existence alluvial mining; while others had journeyed back to Australia or taken up other occupations in New Zealand.

“Yes, that is where Joe Mitchell, a Ballarat boy, camped,” I soliloquised. Only the sods of the chimney foundation were left. Poor Joe was killed at the Invincible mine, at the head of Lake Wakatipu.

A little further down the gully was Joe Halliday’s tent. At one time Joe partly owned the Heart of Oak mine at the Carrick. He came to Dunedin and lived at the rate of £10,000 a year for a while, but the mine petered out and Joe drifted on to Macetown. One Sunday morning he made a large plum pudding and tried to boil it in a leaky kerosene tin. It’s a long story, and full of sulphur and brimstone, but finally Joe kicked the bottom out of the tin and kicked the tin and pudding out onto the road.

Here is an old camp I remember well. B--- lived there. He had not been long in the gully when we found him out in a serious misdemeanour. There was no doubt of his guilt. Some of the miners met that evening and decided to invite him to leave the district or take the consequences … he was given short notice to pack up and clear out.

Before noon the next day we were well rid of his company. He went through Macetown and camped at the Billy [Creek]. Some months later his body was found with a broken neck at the foot of a cliff.

Thoughts like these were crowding through my mind when darkness came on, and I had just resolved it was not worth while staying there all night, when I heard the sound of a horse approaching, and then the cheery voice of Alf Partridge, “Halloa, have you had tea?” I explained my misery, and he told me he had at times experienced a similar feeling of solitude.

But there are others who prefer a lonely life. There is Jack Watkins. He saved enough money to enable him to live comfortably in retirement, and he chose a spot on the mountainside between Macetown and the Eight-mile, and there he lives alone, undisturbed by visitors excepting a weekly call from the packer.

I saw the old chap in the distance the next day as I passed on to Arrowtown. He was walking to and fro in front of his hut, with head bowed as though intently watching the flow of the few remaining grains of sand that measured the ebb of life.[8]

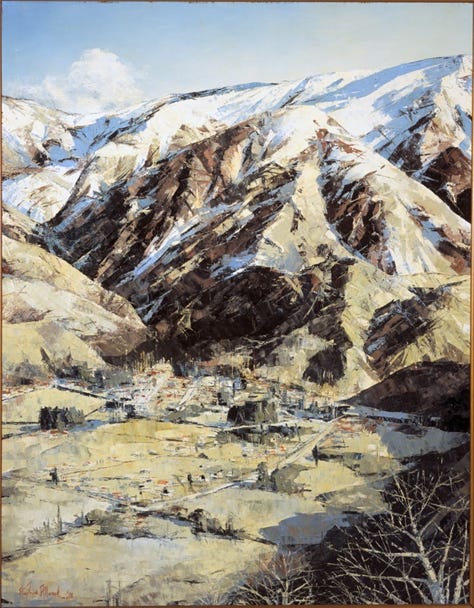

Early Winter Over Arrowtown. Artist Stephen Allwood, 1976. Archives New Zealand. Early Winter Over Arrowtown

Perhaps the region’s inescapable remoteness and a yearning for human company caused the emerging society to emphasise the importance of civility and courtesy. Civility and civilisation were closely associated in the Victorian value set.

People such as Willie, who had had their entire lives on the goldfields, understood themselves as creating a new civil society, especially with European migrants in mind, that they hoped would be superior to the one they or their parents had left in the U.K. Many sought to transform the colony from a rough frontier entity to one based on the rule of law and developing a social consensus on honesty and fair dealings.

In one of his gold-mining reminiscences published in The Otago Daily Times in 1929, Willie reported on his interview with:

that splendid old pioneer miner, Tom Monk … He has been blind for some years, but his memory was quite reliable when I talked over old times with him a few years ago. He and his mate, a Mr Neil McInnes, were amongst the first miners who camped on the head waters of the Shotover, and they built for themselves a hut on what has ever since been known as Monk’s Terrace. That was 64 years ago, and I am told the old gentleman is now 95 years old. He and his partner were great pals, and those who knew them of old have told me they indulged in great politeness to each other. “Will you have a glass of wine, Mr McInnes, before you retire?” “Thank you, Mr Monk, if you will be good enough to join with me.” Years later, when Mr McInnes died, no more sincere mourner existed than his late partner, and he was heard to remark: “There is surely a place in heaven for Mr McInnes.”[9]

Premier Gully - Macetown, 1870-1880s, Otago. Photographers Burton Brothers. Te Papa (O.026465) Premier Gully

An earlier post reported on how commentators of the time said how different the Otago goldfields were from those that preceded them in Victoria and California. Relatively little violence occurred, considering what was often little law enforcement, and there were no recorded instances of lynching. Some attacks on Chinese miners certainly occurred, especially during economic downturns, but these were generally low-level harassment and unsuccessful attempts at intimidation. Yet for many years, Pākehā public opinion demonised Chinese migrants as unacceptably dissimilar on ethnic, cultural, and religious grounds.

A century after the first Otago gold rushes, Salmon was able to reflect that although gold miners were no longer predominant within New Zealand society by that point, they had shaped it in many significant ways. They were largely responsible for the reconnaissance and settlement of inaccessible places so far unknown to Europeans. Gold triggered a population explosion and gave the South Island economic power.

During economic downturns, goldmining provided a safety margin of exports and employment. Rising gold production resulted in purchasing power and exports that created overseas income. New markets and internal commerce emerged around the winning of gold, including an upsurge in pastoral production.[10]

As the reef gold in the mountains gradually petered out, like most others of the former gold adventurers, Willie sought more predictable employment. He joined the Railway Locomotive Department in Dunedin as a locomotive driver and foreman. His letters to local newspaper editors reveal him as an articulate advocate of railway servants’ rights but also as someone who would stand his ground in common principles that he considered important:

I remember when in the railway service some years ago I had occasion to send a young fellow home for scamping his work and insubordination. The following day the parliamentary representative of the district the young fellow lived in came to me for particulars of his offence. I told him as much as I thought necessary, and at the same time I gave him clearly to understand that I would refuse to have him under my charge again, and his advice was, stick to that and never tolerate any man that neglects his work and boasts political influence.[11]

“Some years ago” means before 1899, when he and his brother James founded their sharebroking firm Sligo Bros. In his letter, Willie draws attention to one of the principles his society held as valuable and endeavoured to protect. He had in mind the egalitarianism that people like his parents had instituted in their developing goldfields society. Willie’s generation was attempting to prevent its values from being corrupted by anyone, such as his former railway worker, trying to claim special privileges.

There was further faith in a moral community that possessed collective standards of respect for others and a shared commitment to seeking a better world. These views were based on a largely unspoken conviction that all men and women were fundamentally good and reasonable.

Then, while anyone might deviate from a collectively accepted moral code, their doing so would be understood as a transgression that the rest of society would condemn. A shared communal belief system was reinforced by the institutions to which people belonged, including their churches, friendly societies, unions, lodges, and mutual support or benevolent societies that provided financial assistance to members in times of economic difficulty, illness, or retirement. There was relatively little class consciousness in this world, at least compared with the societies from which they or their parents had come.[12]

Scottish migrants such as Willie’s family could often quote extensively from Scotland’s premier poet, Robert Burns, for example, in The Cotter’s Saturday Night:

Princes and lords are but the breath of kings,

An honest man’s the noblest work of God.

Or quote from his A Man’s a Man for a’ That:

What though on hamely fare we dine,

Wear hodden grey, an’ a that;

Gie fools their silks, and knaves their wine;

A Man’s a Man for a’ that:

The honest man, tho’ e’er sae poor,

Is king o’ men for a’ that.

Statue of Robert Burns between St Paul’s Cathedral and the Dunedin Town Hall. Photographer Mattinbgn, 2011. Statue of Robert Burns

In those days when people memorised poetry in ways largely unknown today, women could readily respond with verse from Burns’ The Rights of Woman.

While Europe’s eye is fix’d on mighty things,

The fate of Empires and the fall of Kings;

While quacks of State must each produce his plan,

And even children lisp the Rights of Man;

Amid this mighty fuss just let me mention,

The Rights of Woman merit some attention.

In addition, the athenaeums to which working people belonged would contain the works of the American political activist Thomas Paine, such as the Rights of Man. Here, he argued that human rights are inherent in the human condition, not awarded by any king or autocrat, and that the government’s role is to protect fundamental human rights, particularly the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

New Zealand had wealth inequalities, but they tended to be smaller than those in the USA, the U.K. or Australia. Accordingly, social divisions based on wealth were less prominent in everyday life experience. Differences in wages earned were not major since labour shortages during early European settlement had resulted in closer pay rates for skilled and unskilled workers than in Britain, the United States or Australia.[13]

The main exception, though, to a widespread belief in the fundamental equality of men and women and the worker’s dignity was a distrust of the Chinese. Europeans expressed hostility towards them, as they might be willing to work longer hours for less money. The Chinese were perceived as so divergent in their ethnicity, religion, culture, working and leisure habits that perceived distinctions among English, Scots, Welsh, and Irish tended to be less prominent. By the century’s end, parliament would institute an infamous poll tax on intending Chinese immigrants, and I report on this in a following post.[14]

People respected physical work and were somewhat suspicious of anyone, especially any man, who appeared to try to avoid physical labour. This principle had its roots in the Calvinist philosophy referred to in previous posts, where each person was expected to be an unremitting labourer until death in this vale of tears, as they said. The idea that physical labour had intrinsic merit and the availability of many more opportunities for self-employment than were possible back in the U.K. or Ireland both tended to reinforce the belief that people were intrinsically equal.[15]

Just as you fell under suspicion if you did not polish your own boots, demonstrating that you were appropriately looking after yourself and doing your best to look respectable, likewise, you were supposed to pitch in and help others in your immediate community who needed your assistance.[16]

Much credit was given to those who could demonstrate practical skills in such pioneer tasks as chopping out bush, draining wetlands, digging ditches, growing vegetables at home, curing their own meat, or preserving eggs from backyard hens. A shared faith in the virtue of hard physical labour reinforced ideas from progressive European thinkers about the value of equality that underpinned Pākehā society.[17]

There was additionally a strong consciousness that all were participating in creating a new society. Although, by the end of the century, the concept of New Zealand as a Better Britain had weakened compared to the notion that the New Zealand Company had tried to sell back in the 1840s, there was still a sense that this country could and should be a better and more moral place to live. People referred to the U.K. as the “Old Country”, but their doing so suggested both rejection and a kind of nostalgic affection.[18]

Society felt self-confident in its ability to pursue progress. Few men or women would have described themselves as Marxists, yet they might have agreed with Marx’s statement that “Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.”[19]

That is, Pākehā arrivals thought or wanted to think they were creating their own future, but they understood the class-based weaknesses of the U.K. that they or their parents had left. They were also mindful of the sectarian divisions based on religion rupturing that society, which the great majority wanted to avoid in Aotearoa.

Athenaeums and Libraries

By the century’s end, as national and local governments increased their workforces, white-collar occupations were growing in size. However, it was not just the office workers who valued access to learning. In the 19th century, the term “mechanic” referred to any skilled manual worker, and Mechanics’ Institutes had appeared in the U.K. as early as the 1820s. They were sources of information and learning for expert workers and came to Aotearoa with the early settlers and were known as athenaeums, the word referring to the ancient Greek temple of Athena, the goddess of wisdom and art. Athenaeums offered a broad collection of classes and lectures and provided libraries and reading rooms where workers could consult books and journals.

Some among the growing middle classes in the expanding range of clerical jobs started to consider themselves socially superior, but skilled manual workers rejected any such perspective. Neither skilled nor unskilled individuals accepted assumptions of higher status for office workers, nor did they think that white-collar workers’ skills deserved a higher pay rate.[20]

Athenaeum, Wellington, 1880s. Photographers Burton Brothers. Te Papa (C.014738) Athenaeum, Wellington

During the 19th century, public libraries were likewise developing in the U.K. and the USA, but many were free. In contrast, the New Zealand ones were mostly user-pays and managed by local committees, although often subsidised by provincial authorities and later by the central government. They might be called literary institute, mutual improvement society, public library, mechanics’ institute, or athenaeum. Between 1840 and 1914, 769 public libraries existed for at least one year. Given the population’s limited extent at the time, a large proportion of the country appears to have had comprehensive access to affordable reading materials, with hardly any centre lacking its public library. By the beginning of the 20th century, New Zealand’s ratio of libraries to people was around one to 2,000, compared to the USA’s statistics, which peaked at about 1:5,000.[21]

Naseby Athenaeum, Central Otago, founded in 1865. Photographer Ulrich Lange, 2005. Naseby Athenaeum

Another difference was that libraries in the USA were considered something to develop when a community generated sufficient wealth to do them well, and they were intended to play a recognised part within a developed social structure and education system. In 1743, Benjamin Franklin proposed that “The first drudgery of setting up new colonies, which confines the attention of people to mere necessities, is now pretty well over; and there are many in every province, in circumstances that set them at ease, and afford the leisure to cultivate the finer arts and approve the common stock of knowledge”.[22]

In contrast, in Aotearoa, reading materials were not seen for gentlefolk at ease wondering how to fill their vacant hours. Instead, books were a first necessity, and libraries and printing presses arrived on the earliest colonists’ sailing ships. Within 40 years of systematic Pākehā colonisation, New Zealand, on a population basis, had more public lending libraries than any other country in the world.[23]

Athenaeum in Lawrence, Central Otago. Photographer Mattinbgn, 2011. Athenaeum in Lawrence

As reported in an earlier post, immediately upon arriving in Dunedin in 1848, the Presbyterian Free Church pilgrims set up a lending library. The town’s spiritual mentor, the Reverend Thomas Burns, was its librarian, God’s gatekeeper of moral enlightenment. On Saturday evenings, when work was done, he dispensed improving books for the citizens’ perusal on the following Sabbath day, when no labour was permitted.

Dr and Mrs Burns. Photographer and date unknown. From the Internet Archive, “Reminiscences of the Early Settlement of Dunedin and South Otago,” 1912, compiled by John Wilson. Dr and Mrs Burns

However, not just the towns featured the fast establishment of libraries. As reported in earlier posts, thirteen years after Dunedin’s founding, rich goldfields were found nearby, to the consternation of the city fathers, and deluges of hopeful diggers, including my great-grandfather Archie, poured in. As expected, Central Otago’s Tuapeka fields were quickly replete with general stores, butcher shops, grog shops, legal or otherwise, and entertainment centres such as dance palaces, gambling houses, brothels, and saloons. But the diggers also demanded reading matter, and subscription lending libraries soon appeared. Four years after gold’s discovery, the region had six lending libraries; by 1886, there were fourteen more.[24]

Athenaeum, Oamaru. Photographer Andy king50, 2011. Athenaeum, Oamaru

In 1890, one New Zealand commentator remarked on how:

We may not be inclined to credit humanity with so much intellectual yearning; but it is only necessary to go through our thinly populated country districts, and see the numerous attempts that have been made in these out-of-the-way corners of the colony to establish public libraries, in order to convince ourselves that intellectual desires are commoner than we might suppose. Poor, these libraries are; but when circumstances are taken into account – the difficulties that country people labour under in selecting and procuring books, and the smallness of the funds at their disposal – the wonder is not that these libraries are poor, but that they are there at all.[25]

Left to right, Wellington Athenaeum (with tower), Colonial Bank of New Zealand Wellington Branch with South British Insurance. Photographer James Bragge, 1879. Wellington Athenaeum

Entrepreneurial journalists responded to the demand for reading matter by founding newspapers. Twenty-eight daily or weekly broadsheets appeared between 1840 and 1848, 181 between 1860 and 1879, and 150 between 1880 and 1889.[26]

In parallel came newspapers and magazines in Māori, the first published by the government in 1842, Ko te Karere o Nui Tireni, followed by a surge of about 40 other Māori newspapers. By late in the century, they were gradually waning, in parallel with the decline in the use of the Māori language.

Families of skilled workers greatly valued public libraries and athenaeums, seeing them as crucial means to acquire new practical knowledge and foster self-improvement. Bookshops and newsagents were also important, including two in George Street and South Dunedin owned by Alex Sligo, Archie’s elder brother and, for a short period, M.P. for Dunedin City, whom I mention in later posts. In a time when very few could or wanted to enter tertiary study, as understood today, people believed their educational endeavours would enhance their independence and life options.[27]

Families accordingly liked to think that they were better-quality colonists compared to some other parts of the world:

A well-conducted Colonist is of necessity a reading man; debarred from the more frivolous amusements of the mother country, he has no other resource but in books, or the debasing influence of the tavern - the bane and antidote of Colonial life. None but they who have resided in a new Colony can appreciate the value of a new book; and we are happy to bear testimony, that in no colony is literature more appreciated than in New Zealand: as might be expected from the very superior class of men who have migrated to our favourite Colony.[28]

Athenaeum, Invercargill, circa 1904. Photographers Muir & Moodie. Te Papa (C.012936) Athenaeum, Invercargill

Libraries also served as social centres for communities, where errant youth who would otherwise get drunk and into trouble could be sent for social supervision. Politicians, newspaper editors and educators extolled the virtues of systematic reading as a way for a community to advance its self-improvement, free itself from superstition and irrational beliefs, and obtain moral instruction.[29]

But by the early 20th century, worries were expressed that the quality of reading was deteriorating in a lamentable fashion. Sir Robert Stout, twice Premier and once Chief Justice, voiced his fear that “The reading of serious books was not popular amongst our people … In the hostels and boarding houses I have not seen a single young person reading a serious book. The newspaper is read, and occasionally a novel is perused … Such newspapers have become a substitute for books”.[30]

Sir Robert Stout, 1914. Photographer Stanley Polkinghorne Andrew. Sir Robert Stout

Reading for leisure and pleasure was starting to supplant the antique Calvinistic prescription that God-fearing adults needed to demonstrate their fitness for heaven by perusing moral tracts penned by sober theologians. Entertainment was the new claim but elected representatives in local and national governments were far from happy. Why, they asked, should they allocate any ratepayer or taxpayer subsidy to frivolous demands such as recreational novels rather than printed materials to improve the community’s moral and practical capabilities? Through responsible reading, individuals would learn valuable skills and avoid erroneous ways, resist the baleful influences of sin in society, and resolve how their own life would proceed as on a latter-day pilgrim’s progress.

Society’s earnest decision-makers still had earlier generations in mind, who were reverential in their focus on a limited array of texts, many of which were religious in character. Prominent among them, especially in the evangelical Protestant communities, was the Bible, whose content was thought essential to memorise and recite in a family or church group. But now, an intensive reading of few documents was being replaced by extensive reading of many texts, few or none of which were to be committed to memory.[31]

A similar transition had occurred in Europe as populations there grew restive at being told what to read and as they discovered the excitement of reading for entertainment and distraction. Commercial lending libraries and reading clubs had bloomed at the turn of the eighteenth century, but worried civic leaders labelled them as “brothels and houses of moral perdition”, corrupting both young and old with debasing doses of frivolous reading.[32]

Artistic Leisure

Now that the Central Otago goldfields were largely played out, a more settled life in Dunedin permitted Willie to develop his artistic skills. The Otago Daily Times reported on the Dunedin School of Art students’ annual exhibition for 1891. Willie was then aged 32, and he and others were seemingly fascinated by the practical artefacts of modernity: “Mr. W. Sligo’s drawings of a steam indicator and locomotive are among the best in the collection, and Mr. F. Shacklock’s bevel wheel and pinion in gear is a capital piece of work”. The paper went on to report that “Messrs M. Cable, A. L. Dowden, P. Shacklock, H. McNicoll, T. D. Mackenzie, J. Cable, and T. A. Hutcheson are also deserving of mention”: interesting that all these art students were males, it seems.

Lake Te Anau, artist W.F. Sligo, 1893.

Devil’s Armchair, Lake Manapouri, artist W.F. Sligo, 1896. Presumably, Lucifer sits in the mountaintop patch of snow to cool his backside after the flames of hell.

Floral study, artist W.F Sligo. Date unknown.

Mirror painting, artist W.F Sligo. Date unknown.

Coming up in future posts:

Norman Conceded in His Mind that the Boomerang Would Crash Home Before He Could Snatch Out His Revolver.

The Sin of Cheapness: There Are Very Great Evils in Connection with the Dressmaking And Millinery Establishments.

The Poll Tax: One of the Most Mean, Most Paltry, and Most Scurvy Little Measures Ever Introduced.

Holy Wells: We are Order and Disorder.

God is Good and the Devil’s Not Bad Either, Thank God.

Notes

[1] Salmon, 1963, p. 218.

[2] Sligo, 1922, p. 6.

[3] Hall-Jones, p. 110.

[4] Salmon, 1963, p. 225.

[5] Beaton, 1971, p. 43.

[6] Griffiths, 1998, p. 109.

[7] Hall-Jones, Goldfields of Otago p. 111.

[8] Sligo, 1922, p. 6.

[9] Sligo, 1929, p. 2.

[10] Salmon, 1963, p. 12.

[11] Sligo, W.F., Letter to the editor, January 30, 1909.

[12] Olssen, Building the new world, pp. 42-3.

[13] Olssen, Building the new world, p. 242.

[14] Olssen, Building the new world, p. 158.

[15] Olssen, Building the new world, p. 247.

[16] Olssen, Building the new world, p. 236.

[17] Olssen, Building the new world, p. 244.

[18] Olssen, Building the new world, p. 233.

[19] Marx, K. (1852).

[20] Olssen, Building the new world p. 244.

[21] Traue, 2005, pp. 323-4.

[22] Traue, 2007b, p. 151.

[23] Traue, 2004, p. 86.

[24] Traue, 2007a, pp. 41-2.

[25] Traue, 2005, p. 335.

[26] Traue, 2007a, p. 46.

[27] Olssen, Building the new world, p. 42.

[28] Traue, 2005, p. 329.

[29] Traue, 2005, p. 332.

[30] Traue, 2005, p. 333.

[31] Traue, 2004, p. 85.

[32] Traue, 2004, p. 88.

References

Beaton, E. (1971). Macetown: The story of a fascinating gold-mining town. John McIndoe.

Griffiths, G. (1998). Southern writers in disguise; A miscellany of journalistic and literary pseudonyms. Dunedin: Otago Heritage Books. No. 9, Southern Heritage 150 Series.

Hall-Jones, J. (2005). Gold-fields of Otago; An illustrated history. Craig Printing.

Marx, K. (1852). ‘The eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte’. Die Revolution, New York.

Olssen, E. (1995). Building the new world: Work, politics and society in Caversham, 1880s–1920s. Auckland University Press.

Salmon, J.H.M. (1963). A history of goldmining in New Zealand. Government Printer.

Sligo, W.F. (1909, 30 January). Letter to the editor, Otago Daily Times.

Sligo, W.F. (1922, 8 July). ‘The old goldfields days. Macetown in the eighties: The old reefs and the old reefers. Some personal reminiscences – No. III’. Otago Daily Times, p. 6.

Sligo, W.F. (1929, 5 June). ‘Old days on the Shotover; A mining retrospect and a new venture’. Otago Daily Times, p. 2.

Traue, J.E. (2004). ‘Fiction, public libraries & the reading public in colonial New Zealand’, Bulletin of the Bibliographical Society of Australia & New Zealand, 28, 4, 84–93.

Traue, J.E. (2005). ‘A paradise for readers? The extraordinary proliferation of public libraries in colonial New Zealand’. Script & Print: Bulletin of the Bibliographical Society of Australia & New Zealand. 29, 323-340.

Traue, J.E. (2007a). ‘Reading as a “necessity of life” on the Tuapeka goldfields in nineteenth-century New Zealand’, Library History, 23, 1, 41–8.

Traue, J.E. (2007b). ‘The public library explosion in colonial New Zealand’, Libraries & the Cultural Record, 42, 2, 151–64.