A Complete Mental Madness Appears To Have Seized Almost Every Member Of The Community.

In these posts, I tell of two of my ancestors who, in 1861, arrived in Aotearoa New Zealand. My Irish great-great-grandmother Maria Dillon landed in January, just a few months before the gold rush that would utterly transform Dunedin and the province of Otago. My great-grandfather, the Scotsman Archie Sligo, was among the flood of hopeful diggers who disembarked in October of that year.

I wanted to learn more about the forces that propelled them from their homelands, what attracted them to their new country, what happened here shortly before they arrived, and what they encountered as they set about making new lives for themselves.

These posts reveal part of their stories.

Previously: An Agent of Popery, The Limb Of Anti-Christ And His Clansmen Were A Hellish Band of Highland Thieves.

I knew that my ancestors Maria and Archie had arrived in Dunedin in 1861, and I also knew that that settlement was still very young, created just 13 years previously. However, I didn’t know much about how the town came to be. Who set it up, what motivated them, and what was the village like before the deluge of gold set it on a wholly different path?

The Englishman Edward Gibbon Wakefield was one of the vital early drivers of the British colonisation of Aotearoa. His aim was to generate income for investors, but even as he was successfully popularising New Zealand as an intriguing new colony in England, to the north in Scotland some people with motives other than profit became interested.

Edward Gibbon Wakefield, author Benjamin Holt, 1826. National Library of Australia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Edward_Gibbon_Wakefield.jpg

Wakefield sensed that a new colonisation scheme for New Zealand might well generate some substantial wealth. While serving a three-year gaol term for abducting a fifteen-year-old heiress he had illegally married, he had the leisure to consider his future. Wakefield was a can-do man who felt in harmony with the self-confident spirit of the times. Businesspeople assumed there could and should be close connections between doing good and doing well financially. They saw ways for them to serve the interests of the expanding Empire, create opportunities for the poor but honest (as they would say then), build new markets, form a strong foundation for new colonies, and generate satisfactory profits through their own energies.

Since the eighteenth century, forced migration was regarded as a proper or even essential way for the U.K. to rid itself of its so-called “criminal classes”, as described earlier. However, new perspectives on the topic were emerging in the form of systematic colonisation. Thomas Malthus’s proposition that European populations were growing well beyond their natural limits was influential, so it appeared logical to ship “surplus” people overseas. Wakefield and others proposed that planned migration to the colonies would comprise a win-win for all concerned.

The rising nineteenth-century Scottish and English businesspeople saw no inconsistency between their revitalised philosophy of Christian evangelism and their drive to foster economic progress and generate wealth. One writer explained how overseas missions would build profits and benefits for all involved. New colonies would boost and protect British commerce by supplying fresh markets, not to mention to:

bring up savage men to a higher appreciation of themselves, to realise their wants and needs, and thus awaken in them healthful tastes. So this grand missionary movement is being felt in our markets that supply the new and increasing wants of the world. In this way profits are reaped and business is benefited.[1]

Wakefield undertook detailed planning to demonstrate that as overseas colonies expanded, further enhancing the Empire, British industry was to benefit from acquiring additional markets, along with guaranteed sources of valuable raw materials. Home population pressures would lessen, and hard-working pioneers would build model colonies. Wakefield had the new settlement of New Zealand in mind, and his concept was that this was to be a Better Britain, freed from the endemic ailments of the U.K., a place where an idealised and improved British society would flourish.

Sir William Molesworth, Wakefield’s friend and a New Zealand Company director, invoked both divine decree and human nature:

We are by nature a colonising people. God has assigned to us the uninhabited portions of the globe, and it is our duty to take possession of them ... to found an empire which might in future ages become the Britain of the Southern Seas.

Sir William Molesworth, portrait by Sir John Watson-Gordon, circa early 1860s. National Portrait Gallery. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sir_William_Molesworth,_8th_Bt_by_Sir_John_Watson-Gordon.jpg

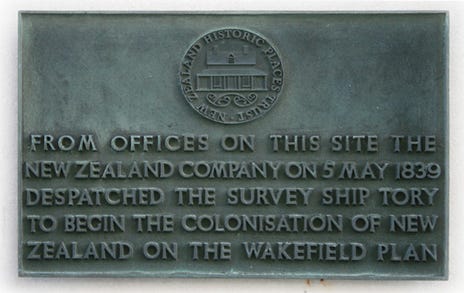

In the 1830s, a collection of English and Scottish capitalists quickly saw the merits of Wakefield’s proposal and set about forming the New Zealand Company to provide a vehicle for a new and different kind of colonisation.[2]

The plan relied on the New Zealand Company buying land cheaply from Māori, then making an enticing profit by selling it to “gentlemen settlers” at a substantial markup. The soil was to be broken in and made suitable for European farming by currently impoverished British immigrants. These, after some years (if they were frugal and understood how to save their money), could well be able to purchase their own small patch of land. However, relatively high land prices and modest wages were intended to keep them as tenants rather than property owners for a reasonable period.

What Wakefield and his backers had in mind fitted well with what many commentators considered the U.K.’s constrained prospects. There, humble labouring families had few means to acquire resources that offered much above a level of famishment. Furthermore, who would anticipate any societal or political changes that could improve the prospects for future generations? As a fresh new colony, Aotearoa surely revealed new possibilities for those willing to invest and unafraid of hard work.[3]

The kind of migrants that the New Zealand Company mainly had in mind were an intermediate grade of recruits, neither the poorest nor richest. The most deprived U.K. labourers often lacked the literacy to learn about opportunities and the social networks that might encourage them to consider leaving. Those at the upper echelons of working people generally had sufficient options in their U.K. lives, so they were mainly uninterested in going elsewhere. In the middle ground between the lowliest and the better-off were potential migrants, able to recognise life alternatives in New Zealand that were not open to them in the U.K.[4]

New Zealand Company Plaque, 1-5 Adam St., London. Photographer Diane Griffiths, 2012. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:New_Zealand_Company_plaque.jpg

Scotland’s Presbyterian Free Church leaders were little interested in profits from land purchases and sales. However, they soon realised that their aspirations for a stricter faith and a holier congregation did align nicely with the New Zealand Company’s notion of a Better Britain. Even before the Disruption had provided a new and well-resourced creed in Scotland, certain key figures, led by the Reverend Burns, had started to bend their minds to where they could create a new Free Church community.

Unconnected to their thinking, since the early 1840s, the Scottish sculptor and politician George Rennie (1802-60) had been mulling over the prospects for a Scottish colony in Aotearoa. He noted how the English were the driving force behind the new settlements at Wellington and Canterbury and saw no reason why a Scottish outpost, reflecting the self-assured character of Victorian expansionism, should not also succeed. Why should the English be taking all the new colonial initiatives? Surely Scotland’s capital, Edinburgh, might be enhanced by a southern younger sibling. A new town, perhaps named Dùn Èideann, the Scottish Gaelic name for Edinburgh, was initially just a dream but started to look feasible once the New Zealand Company had purchased a substantial quantity of land in Otago from Ngāi Tahu in 1844.[5]

Three leaders in the plan for a new Free Church haven were the Reverend Thomas Burns, Captain William Cargill, and John McGlashan, a devout Free Church member soon to take a leading role in the new colony. All of them saw the potential of Otago as a finer Scotland, and in their minds, the new settlement would illustrate what they considered the highest Christian and British values. However, Otago could and should be strictly constrained along religious lines. This contrasted with Rennie’s liberal views. For the time being, though, those involved were able to work together. Rennie and Cargill cooperated in 1843 to write a detailed proposal for the New Zealand Company to create a new South Island colony.[6]

Captain William Cargill and Agnes Moodie Cargill, 1860s. Photographer unknown. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:William_Cargill.jpg

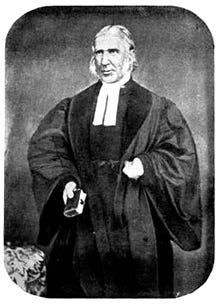

Rev. Thomas Burns, D.D. Author unknown. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Thomas_Burns.jpg

Incompatible differences between the two visions started to emerge. The Reverend Burns discovered that some English Anglicans were interested in purchasing property in the new colony. These had no part to play in his grand vision, and, in his view, these individuals “held second place only to Papists as henchmen of the devil.”[7]

Unbridgeable disparities eventually sank the collaborative venture, and by 1845, Burns and Cargill had eased Rennie out of the plan, completing one further step towards their goal of an exclusively Free Church settlement. The church’s Lay Association under John McGlashan organised ships, advertised the new colony to potential migrants, and made the administrative arrangements for the new community.[8]

Ultimately, two-thirds of the first Otago settlers would be Free Church Presbyterians.[9] Burns and Cargill had been hoping to select only Free Church members. Yet, even after their best efforts at generating publicity, they reluctantly realised that they needed to accept at least some English Anglicans and Scottish people with no connection with the Free Church.[10]

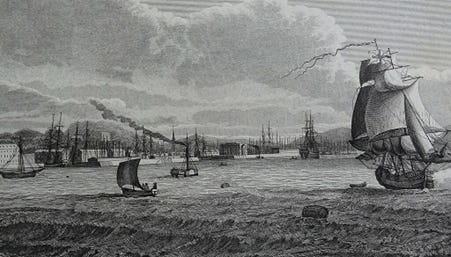

The John Wickliffe, with 97 passengers, made sail from Gravesend in England on 24 November 1847. On 27 November, the Philip Laing departed from Greenock in Scotland with a much larger complement of 247 aboard.

Shipping at Gravesend: The Merchantman ‘Thames’, 1839. Artist Samuel Walters. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Samuel_Walters_-_The_three-masted_merchantman_%E2%80%9EThames%E2%80%9C_under_tow_off_Gravesend.jpg

Greenock and the River Clyde in 1839 with Sailing Ships and Steamers. Artist W.H. Lizars, 1839. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Greenock_in_1839_with_sailing_ships_and_steamers.jpg

On the Philip Laing, life was closely regulated, with compulsory religious services held twice a day and three times on Sunday for good measure. Reverend Burns signalled what later would become in Dunedin his close inquiry into the individual morals of the populace with successive interviews of each passenger. Couples who had made what Burns discovered to be premature conjugal arrangements promptly found themselves in a wedding ceremony. In addition, Reverend Burns’ strict attitude to the use of profane language and drunkenness meant that offenders knew they were in peril of being publicly rebuked in the daily sermons.

In contrast, the days passed in a decidedly relaxed fashion on the John Wickliffe. While there were religious services, attendance at them was described as infrequent and unenthusiastic.[11] By his own account, the 18-year-old Englishman Edmund Smith, who somehow came aboard the John Wickliffe as a passenger, could not explain what drew him to chance his luck.

Indeed, he did not in any way resemble the desired profile of a Scottish Free Church Presbyterian, nor did he have any useful skills. In his memoirs, he freely admitted to lacking any such characteristics. As well, “I must confess to a feeling of sore depression when my friend left me at Gravesend, and I found myself entered on the battle of life with none near either to befriend or assist”.[12]

He was also unimpressed with his fellow passengers’ potential for the colonial endeavour, observing that:

[i]n spite of my own inexperience and apparent unfitness it seemed to me that the Company must have had the greatest difficulty in securing immigrants, for with few exceptions those on board the John Wycliffe [as he called it] seemed utterly unfitted to become the pioneers of a new colony.[13]

Smith had no time for “one married man who made a great profession of religion, but who treated his wife with much unkindness”. U.K. society’s strict adherence to class rules and mores had not vanished once the migrants came on board. He referred to how “some of the cabin passengers looked askance on a young fellow who went about the deck without coat or vest and sometimes minus shoes and stockings’” while he was taking the opportunity to learn about sailing from crew members.[14]

Port Chalmers Municipal Building, Dunedin. Photographer Benchill, 2009. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Port_Chalmers_Municipal_Building_signs.JPG

In a later post, we pick up the story of what happened once the John Wickliffe and the Philip Laing arrived in Otago.

The 1848 U.K. Recession

In previous posts, I’ve explored the immense pressures that young people in the U.K. felt to leave their country and try to build a new life elsewhere. After a spell working as a coal miner, my great-grandfather Archie had become fully aware that his future lay overseas, but he also knew that he had gained some practical experience and knowledge in the mining industry.

In 1848, when he was fourteen, he saw firsthand the effects of a major industrial downturn and subsequent recession in Scotland. However, this economic deterioration came hard on the heels of the Irish Great Famine when tides of migration from that country were occurring, including into Scotland, new arrivals seeking any paid work.

Archie was aware of thousands of destitute Irish, having sold every article they owned except for their clothes, thronging penniless into Glasgow and other major cities. They would labour for bare minimum rates, often undercutting wages, and in the absence of effective trade unions, employment was becoming highly insecure.

Even at peak migration during the Famine, as mentioned in another post, Irish migrants did not exceed three per cent of the population in England or seven per cent in Scotland.[15] Nevertheless, especially in tight recessionary times, this was more than sufficient to reduce the wage rates further that the least skilled could command and make their lives more precarious. While the influx of Irishmen solved pit proprietors’ problems regarding where to find labour, little opportunity now existed for Scottish miners to seek wage increases because of the newcomers.

Irish migration into Scotland and the economic downturn compelled Scottish workers to examine their prospects elsewhere. They all knew that migration was not a new phenomenon. As in Ireland, for generations, Scottish people had seen family members throw the migration dice, whether within their own country or abroad. Since there was no bottom limit to pay levels, Scotland, like Ireland, had a minimally waged and hazardous economy. As the economic recession bit deeply, Archie saw how many were losing their livelihoods and queuing to seek whatever charity was offered.

It was a profoundly unsettling period, with recession and hunger for many families compounding their anxieties in this worrying year of European revolution. The usual illnesses associated with deficient nutrition, including cholera epidemics, invaded cities and towns.

In 1842, mortality from the major killer diseases had been “greater in Glasgow, Edinburgh and Dundee than in the most crowded towns in England”. Everyone could see that as family incomes dropped below subsistence levels, largely incurable infectious diseases such as cholera, typhoid, scarlet fever and smallpox were poised to come roaring back.[16]

Cholera Epidemic Poster New York City, 1865. New York City Sanitary Commission. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cholera_Epidemic_poster_New_York_City.jpg

Women’s Migration

In earlier generations, people tended to assume that they would undertake the same kind of work as their parents, but this no longer applied in conditions of radical change. Just as boys in their adolescence knew they had to understand the best options in their fast-altering society, girls carefully considered the possibilities open to them. Unlike in previous, less turbulent times, adolescent girls and their families decided migration might well be in their future. Girls were said to become adults when they left their families as teenagers to obtain domestic or factory labouring work, generally in a larger town or city.

Farm Women at Work, 1882. Painter Georges Seurat. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Farm_Women_at_Work_by_Georges_Seurat,_1882-83.JPG

Although they tended to move shorter distances, women were likelier to migrate within Scotland than their male counterparts. Then, while Scottish women were often quite prepared to venture to new places within their country, they were less willing than men to leave Scotland.[17]

This difference between the sexes started to influence the choice of potential marriage partners. Young men who had made up their minds to migrate overseas tended to be attracted to women who were also saying they were ready to consider leaving Scotland. Conversely, young women unable to face the trauma of leaving their families behind, in those days probably for their lifetimes, became interested in men who appeared to have the wish and ability to make a living within their country.

A young woman’s interpersonal connections were vital as she pondered a possible voyage beyond Scotland. Women took pains to obtain as much up-to-date information as possible from extended family members or friends already overseas as they came to terms with whether they could start a wholly new life somewhere far distant. Scottish newspapers often contained articles on the strengths and weaknesses of different migrant destinations. Young women felt a constant impetus towards migration. They undertook careful and prolonged discussions within their relational peer groups in social gatherings, homes, and following prayer meetings.[18]

Migrate, But to Where?

As described in an earlier post, just as the Irish were doing, early in the 1850s, potential Scottish migrants looked hard at which colonial destination might suit their talents and offer the best opportunities. Similarly, as in Ireland, later in the decade, anxieties were building about the prospect of civil war in the USA. The long voyage to Aotearoa was still daunting. Still, the unlikelihood of war breaking out in the country’s south and the work openings in Otago were becoming increasingly evident.[19]

But Australia came first. Around 90,000 Scots left for Australia during the 1850s gold rushes.[20] About another 50,000 Scottish migrants arrived in Australia in the post-rush period, and up until 1880, the great majority had occupations as general labourers and domestic servants. Also, following the gold rushes, many received some support from colonial governments. While the vast majority of the gold rush Scots came out as single travellers, after that, a much larger proportion of females also made the voyage. In all, men outnumbered women in a ratio approaching three to two.[21]

The Australian Madness

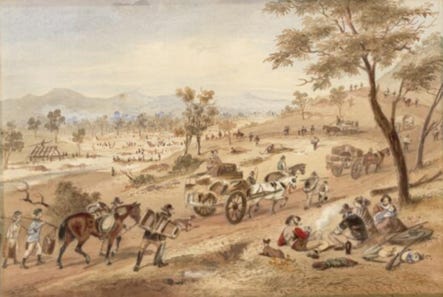

In 1851, tremendous excitement attended the discovery of gold in New South Wales. The Bathurst Free Press scolded: “A complete mental madness appears to have seized almost every member of the community. There has been a universal rush to the diggings”.

In April 1851, Australia was in a paroxysm of gold fever. The dam had burst in Sydney, and the roads that wound through the Blue Mountains were clogged with columns of hopeful diggers: men who were fully familiar with outdoor work and many who were not. Offices and shops in the city were stripped bare: grocers’ assistants, clerks and their managers, lawyers, curates, government officers, schoolteachers, all slogged along elbow to elbow with stableboys, sailors deserting their ships, soldiers and policemen with or without leave of absence, stooped under the weight of shovels, picks, hastily purchased food supplies, tents and blankets.

As they slushed their way through that autumn’s indifferent rains: “[i]t was as though a plug had been pulled and the male population of New South Wales had emptied like a cistern, in a rush towards the diggings”.[22]

Charles La Trobe, 1855. Artist Francis Grant. State Library of Victoria. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Charles_La_Trobe_Portrait.jpg

Governor La Trobe was said to be at his wits’ end, telling how:

within the last three weeks the towns of Melbourne and Geelong … have been in appearance almost emptied of many classes of their male inhabitants. Not only have the idlers and the day labourers thrown up their employments and run off to the workings, but responsible tradesmen, farmers, clerks of every grade, and not a few of the superior classes, have followed. Cottages are deserted … business is at a standstill, and even schools are closed … The ships in the harbour are in a great measure deserted.[23]

Just six months after the gold rush in New South Wales, gold was revealed at Ballarat, Victoria, shortly later at Bendigo Creek. An upsurge in the national economy followed with the arrival in Australia in 1852 alone of 370,000 immigrants. In merely two years, Victoria’s populace mushroomed from 77,000 to 540,000, and during the 1850s, that state furnished more than a third of the world’s gold output. The local bureaucracy could not cope with Victoria’s massive and sudden growth, usually comprising single men, occasionally with families, in quest of the newly found gold.

Rush to the Ballarat Goldfields in 1854. Painter S.T. Gill, 1872. National Library of Australia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gill_Ballarat_goldfields_1854.png

By the early 1850s, when teenaged Archie first learned the enthralling news of colossal gold finds in Australia, he had seen the writing on the wall, confirming the feeling that his best chances lay elsewhere. He now understood the ramifications of Scotland’s fast-advancing industrialisation. He realised that humdrum wage labour offered him few or no possibilities to shape his life in any way that seemed meaningful. This awareness was starting to propel him towards seeking his fortune overseas.

In addition to building his skillset in mining, Archie enlisted in the British merchant navy for some time,[24] exploring his options, seeking to be as well-equipped as possible to take advantage of what might present itself. On hearing of the great gold discoveries in Victoria in his late teenage years, Archie determined to try his luck there.

Washing Out The gold, Victoria Gold Rush, 1855. Sketch of the Victoria Gold Rush from George Henry Wathen’s 1855 book on the Golden Colony - View on Campbell’s Creek, Mount Alexander. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wathen,_George_Henry_-_Victoria_gold_rush_sketch.jpg

The lure of gold in Australia was important, but success as a digger might enlarge his options beyond the gold alone, enabling him to buy a patch of land in a new colony. He knew this was out of the question for someone with limited resources like himself in Scotland. He and his wife-to-be could potentially raise a family in a new and freer environment.

We do not know the date of Archie’s advent in Australia, his emigration details being elusive to date. It is possible that he arrived as a merchant seaman and either jumped ship or was permitted to sign off. Official administrative archives of the day are far from complete, Victoria having separated from New South Wales only on 1 July 1851. Some Victorian immigration records covering 1853 to 1923 were lost.

Also, the sheer volume of would-be miners overwhelmed the new state’s ability to document the immigrant influx. The surge of adventurers pouring off their sailing ships just berthed from New South Wales, California, and the U.K. had “flatly declined to recognise the authority or obey the regulations of the responsible powers”.[25] The peak years for that invasion of hopeful diggers were 1852 and 1853.

Archie’s disembarking in Australia perhaps in 1851 or 1852, aged 17 or 18, put him amidst a gigantic population transfer from the old world to the new, the Australian madness as the English were calling it. As the electrifying news of immense gold discoveries in Australia splashed across the U.K. newspapers, shipowners frantically adapted their vessels to maximise the number of adventurers they could haul to the southern hemisphere.

Archie was not travelling with any government assistance. Still, he was among the early surge of Scotsmen who was prepared to spend three months or longer on a sailing ship. Along with many other Scots, the teenaged Archie was drawn to the far-distant Antipodes by the lure of Victorian gold. Now familiar with mining practices, he could see the hunt for gold as a way to determine his life trajectory, make his own decisions and break free from the gradually tightening bonds of industrial capitalism.

In forthcoming posts:

A State of Abject Poverty and Powerlessness, Denying Them Church, Language, Education or Recourse to Law.

As Ever Proceeded from the Perverted Ingenuity of Man.

Muskets Became an Ill-fated Necessity as the People Prepared to Defend Themselves against Northern Aggression.

The People Were Offered up as a Sordid Sacrifice on the Glittering Altar of Commerce.

The Peace of the Pākehā is More to be Feared Than His War.

The Missionary, the Bishops, and the Drunken Whalers.

A Pure City of God on Dunedin’s Unsullied Hills.

The Independence and Cheek of the Labouring Class, Particularly of Female Domestic Servants, Is Beyond All Endurance.

Squatters Rush in, Rabbits Rampant, and Too Many Flocking Sheep.

Gold, a Wedding, Injury, and One More Throw of the Dice.

An Irruption of Strenuous Men, a Ranting, Roaring Time.

But the Thief, Complete With Door, Outran Him and Disappeared into the Raggedy Ranges.

Saddle Hill: Beyond Dunedin’s Disgusting Malodorous Effluvia and a Pestilence of Blowflies.

“Well, No”, Countered The Digger, “But I’ll Give You Sixpence if You Polish Me Boots”.

A Burden Almost Too Grievous to be Borne and Making Shipwreck of Their Virtue.

The Irish Spiritual Empire, a Cycle of Sectarian Epilepsy, and a Certain Fat Old German Woman.

Better at the Language Than Those Who Owned It and Equally Determined to be Both Themselves and to Conform, Fit In.

I Found It a Matter of No Small Difficulty to Collect the Bills Due by Females Who Have Been Assisted to the Colony.

Her Skirt Would Stand up Straight and Have To Be Thawed Out.

His Wife Burst into Tears, Saying She Had Already Mortgaged Their Home so She Could Pay for Her Own Dredge Speculations.

An Irresistible Feeling of Solitude Overcame Me. There Was No Sound: Just a Depressing Silence.

Norman Conceded in His Mind that the Boomerang Would Crash Home Before He Could Snatch Out His Revolver.

The Sin of Cheapness: There Are Very Great Evils in Connection with the Dressmaking And Millinery Establishments.

The Poll Tax: One of the Most Mean, Most Paltry, and Most Scurvy Little Measures Ever Introduced.

Notes

[1] Devine, To the ends of the earth, p. 203.

[2] Belich, Making peoples; Simpson, The immigrants, pp. 46, 81.

[3] Belich, Making peoples, p. 309.

[4] Belich, Making peoples.

[5] Brooking, And captain of their souls, p. 25.

[6] Brosnahan, ‘Being Scottish’, p. 24; Brooking, And captain of their souls, p. 31.

[7] Brooking, And captain of their souls, p. 36.

[8] Brooking, And captain of their souls, p. 43.

[9] Lenihan, From Alba to Aotearoa, p. 63.

[10] Patterson et al., Unpacking the kists, p. 66.

[11] Brooking, And captain of their souls, p. 64.

[12] Smith, Early adventures, p. 20.

[13] Smith, Early adventures, p. 24.

[14] Smith, Early adventures, pp. 26-27.

[15] Fitzpatrick, ‘A peculiar tramping people’, p. 633.

[16] Devine, The Scottish nation: A modern history, p. 167.

[17] McLean, ‘Reluctant leavers?’ p. 112.

[18] McLean, ‘Reluctant leavers?’ p. 114-115.

[19] Brooking, And captain of their souls, p. 117.

[20] Devine, To the ends of the earth, p. 86.

[21] Devine, To the ends of the earth, p. 165.

[22] Hughes, The fatal shore, p. 519.

[23] Gold! Immigration and population.

[24] Hodgson, personal communication.

[25]The Australasian gold fields, pp. 7-8.

References

The Australasian gold fields; The investors’ review. (1934). London Caledonian Press.

Belich, J. (1996). Making peoples: A history of the New Zealanders. The Penguin Press.

Brooking, T. (1984). And captain of their souls: An interpretative essay on the life and times of Captain William Cargill. Otago Heritage Books.

Brosnahan, S. (2003). ‘Being Scottish in an Irish Catholic Church in a Scottish Presbyterian settlement: Otago’s Scottish Catholics, 1848-1895’. Immigrants & Minorities, 30, 1, pp. 22-42.

Devine, T.M. (2011). To the ends of the earth: Scotland’s global diaspora 1750-2010. Allen Lane.

Devine, T.M. (2012). The Scottish nation: A modern history. Penguin Books.

Fitzpatrick, D. (1989). ‘‘A peculiar tramping people’: the Irish in Britain, 1801-70’. In A new history of Ireland, vol. 5, Ireland under the union, I, 1801-1870. W.E. Vaughan (Ed.). Clarendon Press, pp. 623-660.

Gold! Immigration and population. (n.d.) https://www.sbs.com.au/gold/story.php?storyid=49

Hodgson, M. (2011) personal communication citing Archie as listed in the National Archives (UK) Register of Seamen’s Tickets 1845-1854.

Hughes, R. (1998). The fatal shore: A history of the transportation of convicts to Australia 1787 – 1868. The Folio Society.

Lenihan, R. (2015). From Alba to Aotearoa: Profiling New Zealand’s Scots migrants 1840-1920. Otago University Press.

McLean, R. (2003). ‘Reluctant leavers? Scottish women and immigration in the mid-nineteenth century’. In The heather and the fern: Scottish migration and New Zealand settlement. T. Brooking & J. Coleman (Eds.). University of Otago Press, pp. 103-116.

Patterson, B., Brooking, T. & McAloon, J. with Lenihan, R. & Bueltmann, T. (2013). Unpacking the kists: The Scots in New Zealand. McGill-Queen’s University Press & Otago University Press.

Simpson, T. (1997). The immigrants: The great migration from Britain to New Zealand, 1830 - 1890. Godwit Publishing.

Smith, E. (1940). Early adventures in Otago. W.D. Stewart (Ed.). Coulls Somerville Wilkie & A.H. Reed.