In these posts, I tell of two of my ancestors who, in 1861, arrived in Aotearoa New Zealand. My Irish great-great-grandmother Maria Dillon landed in January, just a few months before the gold rush that would utterly transform Dunedin and the province of Otago. My great-grandfather, the Scotsman Archie Sligo, was among the flood of hopeful diggers who disembarked in October of that year.

I wanted to learn more about the forces that propelled them from their homelands, what attracted them to their new country, what happened here shortly before they arrived, and what they encountered as they set about making new lives for themselves.

These posts reveal part of their stories.

Previously: Squatters Rush In, Rabbits Rampant, and Too Many Flocking Sheep.

In earlier posts, I described how Archie realised how constrained his life options were should he remain in Scotland. He recognised his time as a period of radical social and industrial change. Still, he also knew that prospects outside the UK were the only realistic options for winning security and perhaps prosperity for working men like himself.

Archie was portrayed as a loner with a strong sense of following his own direction. He was slightly built and of average height, with an oval face and sharp blue eyes.[1] Yet he cannot have been too lightly built since he preferred outdoor life and work, such as being a carter and quarryman, that demanded physical strength and endurance.

Like New Zealand, Australia had been less attractive than North America because of its extreme distance and people’s lesser knowledge of it. However, the massive new goldfields changed everything. Everyone had learned about the wealth that Californian gold had delivered to many from 1848 onwards. The revelation of immense and lucrative goldfields in Australia altered the equation and made the Australasian colonies appear suddenly alluring.

Seeking Fortune - Emigrant Boy, 1887. Artist Nicholas Chevalier. Seeking Fortune

The New South Wales and Victoria gold discoveries from 1851 and then during the rest of the 1850s attracted over 600,000 migrants. Something approaching half a million were from the UK, with 300,000 from England and Wales, 100,000 from Scotland, and 84,000 from Ireland. Of the people from the UK who flowed into Victoria, only a third had an assisted passage. The rest, like Archie, paid their own fare in the hope of doing well from gold or arrived as working seamen on ships.

The numbers leaving Scottish ports for Australia were just 541 in 1851, multiplied by ten to a high of 5450 in 1852, dropping somewhat to 4166 in 1853, then reducing to 2699 in 1854 as it became more evident that the easier-to-find alluvial gold in Victoria was fast diminishing.[2] We do not know precisely when Archie set sail for Australia, but he was among the thousands in the early 1850s seeking his fortune in the Victorian goldfields.

Entrance to the Diggings, Victoria, by H.B. Stoney. Entrance to the Diggings

Jessie McDonald

Late in the northern summer of 1854, a 19-year-old Glaswegian, Jessie McDonald, made emotional farewells to her friends and family and left her home. She travelled south into England and embarked from Liverpool on the ship Sultana, bound for Melbourne. Jessie had every reason to think that her leave-taking was forever. This made her a little untypical since, as reported in an earlier post, Scottish women were quite prepared to up stakes and move within their own country but were less likely than men to migrate abroad.

Original Plans of the HMS Sultana, 1700s. Author unknown. HMS Sultana

Then, the hazards and costs of the arduous three-month voyage by sailing ship to the other side of the planet were such that people did not undertake their travels lightly and did not expect to return. She was also aware that she was escaping a major cholera epidemic that caused multiple fatalities in Glasgow during 1853 and 1854. This was the third onset of carnage in her home city from the dreaded and incurable disease.[3]

Jessie has been described as an energetic and petite young woman with a round face, big blue eyes, and honey-blonde hair. In Glasgow, she had worked as a domestic maid in one of the quickly growing middle-class families. Jessie was born in a south Glasgow suburb, then Tradestown, now Tradeston. Glasgow’s population had exploded in the half-century before Jessie’s birth, from around 30,000 people in 1770 to over 200,000 by the 1830s.

Important in these influxes were the Highlanders, displaced from further north in the aftermath of Culloden and the population clearances, which likely included Jessie’s own family. Jessie’s was one of the largest Highland clans, McDonald of Clanranald. Hers had been among the first clans to join Bonny Prince Charlie and the Jacobite cause, and hence, it was to be among the most maltreated after the prince’s defeat at the Battle of Culloden in 1746.

Member of Clan Macdonald of Clanranald, by R.R. Mclan, circa 1845. From The Highland Clans of Scotland; Their History and Traditions, published by Eyre-Todd in 1923. Clan Macdonald

After the Highland Scots’ aspirations had been annihilated at the battle, the McDonalds and other Jacobite clans, such as the Camerons and MacGregors, were particularly targeted for retribution and progressively stripped of their lands, rights, and entitlements.[4]

Castle Tioram, Traditional Seat of the Clan MacDonald of Clanranald. Photographer Russell Wills, 2010. Castle Tioram

The McDonalds were part of a Scottish diaspora who took flight southward into whatever employment they could find within the UK and overseas. The century of hard times following the defeat at Culloden taught every McDonald family that some or conceivably all of their members had to emigrate. North America, both the USA and Canada, was a major destination during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Prince Edward Island was the new home for 300 McDonalds from Clanranald in 1790, while the MacDonnells of Glengarry lent their name to Glengarry County, Ontario.[5] Not coincidentally, one of the McDonald mottos is per mare per terras (by sea and by land), the journeying motif thus signalled.

Tartan for MacDonald of Clanranald. Photographer Micheletb, 2020. Clanranald Tartan

Following the Highland inflow into Glasgow came the Irish. When Jessie was about ten, she saw mounting numbers of Irish men, women, and children in rags and starving, having sold virtually everything they owned, straggling into her city. They were fleeing the Great Famine and desperate for agricultural, industrial, or any other work that might exist.

It was, of course, not just the Scots who saw the necessity to leave. More widely in the UK, ordinary working people without resources had few opportunities to rise above their constrained station in life. In their home country, “the working man from the cradle to the grave lives little above starvation and has nothing to hope for”.[6] But those who were not the most impoverished, who had some small amount of capital, saw emigration as their best and perhaps their only realistic option for release from an otherwise inescapable poverty trap.

The Emigrant Ship. Artist Joseph Swain, Wellcome Collection. The Emigrant Ship

Because the storage space on nineteenth-century sailing ships was strictly limited, intending Scottish migrants had to carefully consider the most necessary and precious possessions they could take. Their most common storage item was a plain pine chest, known as a kist. For the Presbyterian Scots and Anglican or Methodist English, this would contain a Bible, considered the most essential of their reading matter. Migrants’ families gave them readily portable keepsakes such as pieces of jewellery, pictures of family, cutlery, cooking utensils, wooden plates and basic carpentry tools.[7]

Australian Emigrant Ship, 1873. From Australian Town and Country Journal, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales. Australian Emigrant Ship

Jessie disembarked in Melbourne on 12 December 1854, doubtless discomforted at her first experience of an Australian summer, dressed as she would have been in the period’s heavy, durable garments. It was unusual and unacceptable for a single young woman without marriage prospects to travel alone, if so, being regarded as “morally suspect”.[8] Many young unmarried women did head off for the colonies, but as reported in earlier posts, they went in organised groups and had an older woman as chaperone.

The Eureka Stockade

As soon as she arrived, Jessie would have been shocked to learn of the armed conflict at the Eureka Stockade, a pitched battle between diggers and colonial troops just nine days earlier in Ballarat, about 115 kilometres from Melbourne. Her first thought had to be whether Archie was there and if he had been hurt. At least 21 miners and six colonial soldiers were killed, and many others were seriously wounded on both sides. The provincial authorities’ uncompromisingly deadly response to the rebellion put paid to any further digger plans for an uprising.

Eureka Stockade Riot, Ballarat, 1854, by John Black Henderson. State Library of New South Wales. Eureka Stockade

Yet, at the same time, the state government recognised that the diggers had legitimate grievances. In this age, working people were starting to insist that they had a fair claim to have a voice in their country’s decision-making. The sentiment was growing in colonies such as Australia that citizens deserved to be unshackled from old European systems that awarded great prosperity and privilege to the few and virtual servitude to the many. Miners were increasingly angered by the colonial authorities’ autocratic and repressive behaviour towards them. They also asked why it was, since they were residents and had to pay a hefty fee for a mining licence, they had no vote and hence no say in how the colony was being run.

Following the Eureka Rebellion, the state of Victoria belatedly realised that it had to acknowledge powerful public support for the diggers, accepting that their complaints were justified. A few months later, in 1855, the state instituted a more user-friendly system to manage the goldfields. It created a miner’s right, which, for a small annual fee, permitted individuals to mine, own land, and vote.

In this way, Victoria became a world leader, and each male digger became an elector with the same status as a wealthy man. Shortly after, the next state parliament broadened the franchise so that every man, not just miners, got the vote.[9] Women’s suffrage took another half-century, with women (except those designated as “aboriginal natives”) aged 21 and older gaining the ballot in federal elections in 1902, while women in the state of Victoria won voting rights six years later.

Working a ‘Long Tom’ to Wash Out Gold at the Bendigo Diggings, Victoria, Australia, circa 1857. From The Australian Picture Book, National Library of Australia. Long Tom

The exact nature of Jessie’s relationship with another young Glaswegian whom she would shortly marry, Archie, is uncertain. But she was likely travelling to Melbourne to be with the young Scotsman who had preceded her to the Antipodes. Family history has it that Archie had spent time working in the Glasgow coal pits, and hence, Glasgow was where he learned his first mining and quarryman skills and met Jessie McDonald.[10]

Wedding

Six months after Jessie’s arrival, on 6 June 1855, she and Archie married in the Presbyterian Free Church Manse, Swanston St., Melbourne. Their wedding certificate reveals that both could sign their name, which was not always the case among young workers. Archie’s signature speaks of rigorous education, almost copperplate, large, bold, and precisely on the line: Arch Sligo. Jessie (Jesfie, in the style of the period) signed her name in precise small letters, but with her surname starting to venture up off the line as if now, at the ceremony’s closing, she was being distracted by other things.

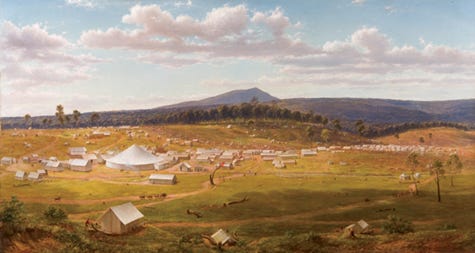

Gold Field of Mount Alexander, Victoria, by H.B. Stoney. Mount Alexander

At their wedding, Archie and Jessie lived in Richmond, an early settlement in Melbourne. Archie was working as a carter, and as such, he was an expert in managing horse-drawn wagons and the bullock dray, the latter sometimes regarded as the semi-trailer of the nineteenth century. The bullock driver was called a bullocky, his wagon drawn by up to 16 or 18 animals, especially on the long hauls. Bullocks provided the first heavy transport from and to the emerging goldfields, extracting timber and transporting supplies to the widely dispersed mining shanty towns, outback hamlets, and sheep and cattle stations.[11]

Bullock Team, 1891. Artist Frank P. Mahoney. Art Gallery NSW. Bullock Team

By 1854-5, the export of a fortune in gold had resulted in an explosion in Victoria’s economic activity. These gold discoveries paid for an enormous inflow of imports, an unheard-of volume of business investment, and an extensive new local market for produce and manufactured goods. This meant employment security as a carter and an income for Archie well above what he had had in Scotland. Yet the economic boom also demonstrated further possibilities, as he saw migrants strike it rich on the goldfields. In common with many others, he would have likely diversified his earnings by working on his weekends as a digger.

On 6 June, their wedding day, the Melbourne Argus’s classified section had an advertisement for “Two Men as Carters, Wages liberal. Apply at Walker’s fellmongery, Richmond.” And it was in Richmond in Melbourne, where the couple lived for the rest of 1855. Over the next several years, Archie worked in occupations linked with the rapid infrastructural development of Melbourne and its regions, including building the Yan Yean reservoir, around 30 km to Melbourne’s north. From the mid-1850s, this was being constructed to provide a much-needed permanent water supply for Victoria’s fast-growing premier city.[12]

Yan Yean Reservoir, Victoria. Yan Yean village in the background. Photographer Graeme Bartlett, 2009. Yan Yean Reservoir

Extensive carting work was required for the substantial earthworks involved, including hauling voluminous water pipes between the reservoir and the city. It was probably there that Archie started to create his expertise in civil engineering to meet the demands of reservoir building. Years later, in Dunedin, his position as a waterworks inspector employed this experience in tandem with half a lifetime of engineering work associated with gold mining.

Ballarat in 1853-54. Artist Eugene von Guerard. Ballarat 1853-54

In 1856, Archie Junior was Jessie and Archie’s firstborn but lived less than a year. He was buried in the Yan Yean Cemetery in what appears to have been an unmarked grave. Funerals were familiar to the family, as many children died young in the primitive and dangerous environments of Australia and Aotearoa’s nineteenth-century settlements. New-born babies, often unnamed, were interred in unmarked graves on the verges of the goldfields’ rudimentary canvas towns.

As Archie and Jessie quietly reminded each other, the Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away. Poverty and the certainty that many infants would die young made headstones unaffordable and unlikely. The Ballarat Star of 29 September 1860 described prodigious railway works at Lethbridge:

The scene … took us completely by surprise. As far as the eye could reach were tents scattered in every direction. We passed some small mounds of earth – these were the graves of workmen’s children – this was the cemetery.[13]

Archie and Jessie’s second son Alexander was born on 6 December 1858 in Yan Yean, while William Finlay (Willie) was born less than a year later on 15 November 1859 at Lethbridge, a little south of Ballarat in Victoria. This made Willie the second eldest child of the nine who lived longer than one year. His given names were in memory of Jessie’s father, William Finlay McDonald.

Fossicking For Gold. Artist J. Miller Marshall, 1893. National Gallery of Australia. Fossicking for Gold

The territories through which the family moved were the ancestral lands of the Dja Dja Wurrung, Waiworung, and Wathaurong peoples. Much devastation to these populations occurred from the early 1830s to the late 1840s through diseases such as smallpox, tuberculosis, influenza, chicken pox, syphilis, and measles, along with deaths from warfare with the incoming pastoralists and settlers’ massacres. The radical depopulation of the Indigenous people by the early 1850s makes it uncertain whether the family had any contact with them.[14]

On Willie’s birth certificate, Archie’s occupation was stated as a quarryman, and there was a substantial railway quarry in Lethbridge, where Archie was probably working. By 1857 in Victoria, most of the alluvial gold to be retrieved by the relatively simple extraction methods of the day had been won. Hence, the mining industry was passing into the hands of better-off individuals and companies with the resources to invest in the more sophisticated technology required to extract gold as it became harder to retrieve. Diggers were finding it necessary to build and broaden their skill base and compete for whatever work that might come their way.[15]

The Ballarat Star of 29 September 1860 further portrays how, in the Lethbridge quarry:

From 1500 to 2000 men – masons, carpenters, sawyers, blacksmiths, quarrymen, excavators, stone breakers, and multifarious others, representing every variety of skilled and unskilled labour – were mixed up here with horses, scaffolding, and steam engines, while the sound of many hundred voices mingling with the clang of anvils, the stroke of hammers, the letting off steam, and the occasional blasting of quarries, presented a picture altogether so wild and extraordinary that a stranger is taken completely by surprise.

Quarrymen were an elite among the occupations at Lethbridge, as signalled by their daily rate of 14 to 15 shillings, almost double a labourer’s pay. This contrasts to carpenters, 12 to 14 shillings; platelayers, 10 to 12 shillings; excavators, 10 shillings; and ordinary labourers, seven and sixpence to eight shillings per day.

Archie could likely demonstrate that his prior experience as a miner in Scotland had furnished him with the necessary capability for that sought-after position. Yet, working anywhere in a quarry was gruelling and hazardous, and silicosis disease from inhaling quarry dust often caused early death.[16]

The Ballarat Star also noted how “in quality and abundance Lethbridge possesses the best quarries in this colony”. It was a point of local pride that stone from Lethbridge quarries was a feature of several significant buildings in Melbourne, such as the steps leading to its Parliament House.[17]

Gold Panning in Australia, 1900. Photographer unknown. Tyrrell Photographic Collection, Powerhouse Museum, Sydney. Gold Panning

After several years, Archie and Jessie acknowledged that they had learned to survive and thrive in this harsh environment. The Victorian goldfields were chaotic and endlessly difficult. Still, they thought their privations there may not have been worse than in the industrial slums of their home city of Glasgow. Importantly, Archie and Jessie now had some sense of being able to set their destiny, no longer entrapped within industrial wage work or stuck as domestic labourer in a rigid class system.

They also observed transitions in gold mining. Successful winning of gold increasingly demanded substantial capital for deeper mining, more sophisticated technology, and the organisational resources to register and run a company. As the search for gold changed, as they said, from poor man’s to rich man’s mining, it became the preserve of corporate bodies. Archie and his friends could see how the ability of solo miners or even small teams to obtain payable gold was progressively in decline.[18]

Injury

By mid-1861, the quarry’s major work was done, and its workers were gradually dispersing, seeking alternative employment. Indications are that Archie returned to his carting work, probably with a transport firm called Williams & Co. The company is recorded as “recommending” he be admitted to Ballarat Base Hospital on 3 June 1861. We do not know why Archie required medical care, but the reference to a company makes an industrial accident the most likely reason. In any event, his stay there lasted until 17 June, indicating a reasonably severe infirmity.[19]

Ballarat Base Hospital, opened in 1855. Photographer Mattinbgn, 2011. Ballarat Base Hospital

On leaving the hospital and recuperating with his family, Archie had the opportunity to think and take stock of his life. He had lost his job and was unfit for heavy physical labour. He and Jessie had two infant sons, and a third child was now on the way.

By mid-July 1861, shortly after Archie’s release from Ballarat Hospital, news of a promising gold find in Gabriel’s Gully on the Tuapeka River in Otago, New Zealand, was starting to filter back to Victoria.[20] Although there was more rumour than hard facts, Archie and Jessie must have seen their chance to get in quickly.

As ever, fables of vast wealth for all expanded into the space left by an absence of factual information. Yet it certainly seemed to be the case that an abundance of gold was wending its way under armed guard down the mountainous trails from Central Otago into Dunedin. A New Zealand mania was replacing what the English newspapers had called the Australian madness ten years earlier, as miners felt the cold wind of harsher times and sought new options. About 23,000 hopeful would-be diggers would venture by sailing ship across the turbulent Tasman Sea by December of that year.[21]

Because of Archie’s skills and experience, the family’s financial situation was better than many others. But should he have been permanently incapacitated or even killed, his family’s position would have been dire. No social security, as understood today, existed at that time.

Jessie and Archie had encountered life’s hazards in Glasgow and on the goldfields and were well aware of the perils that faced miners and their families. One writer claimed that of every hundred diggers, over several years, around twenty died, thirty were injured, or the harrowing conditions in which they worked damaged their health, while twenty went missing. Just ten retained a financial position equal to when they started; the fate of ten was unknown, and only another ten could expect to achieve any substantial success.[22]

The couple were well aware of very pessimistic accounts of goldfield life such as this one, just as they had heard the most starry-eyed portrayals of the wealth to be won. They would have discussed such statistics before deciding Archie should leave for Otago. They were not credulous new chums fresh from the old country and knew there was a much better than ten per cent chance of doing well. During their years in Victoria, Archie had built his knowledge of mining and the infrastructural work that always accompanied the hunt for gold. They had proven their ability to cope with Victoria’s enormously demanding pioneer environment. They also understood it was fortuitous for their family that the Otago and Aotearoa West Coast goldfields were opening up right at the point when the Victorian alluvial fields were becoming exhausted.[23]

Moreover, they had heard that Aotearoa was a mountainous, seagirt land with many resemblances to their homeland. Otago, where Archie was bound, had just thirteen years earlier been settled by Scottish Free Church Presbyterians. Six years ago, they had been married in the Free Church manse in Melbourne, so they had a sense they would feel secure within the Dunedin culture. The word was getting around their Scottish friends, with people describing the country as “not so warm as Australia nor so cold as Scotland”.[24] Could it be like an Antipodean homecoming for them?

Mountains, Central Otago, 2015. Photograph by the author.

In addition, Archie was to arrive there in spring, a season of renewal and hope, a new beginning for the family. They sought what the vast majority of other migrants longed for. They wanted their own place, one from which no callous landlord might evict them on a whim, perhaps a patch of ground to grow food or graze a few animals.

The prospect of owning their own bit of soil was especially attractive to the Scots. In their country, just two per cent of adult males were landowners compared to twelve per cent in England.[25] The proportion of landowning Scottish women would have been vanishingly small. They fully understood how being condemned to renting for life disempowered them. People desired to save a little to provide a financial cushion when their working days were finished. They wanted their children to grow into adulthood with greater aspirations and opportunities than they had had.[26]

They had done well with their savings so far, for Archie knew that he had left Jessie with enough money to sustain her and the children for many weeks or months before he could ask her to take ship to join him. Taking a pregnant wife and two infants to a wholly unknown new territory would be a venture too far. So the couple resolved on one more roll of the dice, hoping Archie could generate sufficient income to put the family’s security beyond further threat.

Coming up in future posts:

An Irruption of Strenuous Men, a Ranting, Roaring Time.

But the Thief, Complete With Door, Outran Him and Disappeared into the Raggedy Ranges.

Saddle Hill: Beyond Dunedin’s Disgusting Malodorous Effluvia and a Pestilence of Blowflies.

“Well, No”, Countered The Digger, “But I’ll Give You Sixpence if You Polish Me Boots”.

A Burden Almost Too Grievous to be Borne and Making Shipwreck of Their Virtue.

The Irish Spiritual Empire, a Cycle of Sectarian Epilepsy, and a Certain Fat Old German Woman.

Better at the Language Than Those Who Owned It and Equally Determined to be Both Themselves and to Conform, Fit In.

I Found It a Matter of No Small Difficulty to Collect the Bills Due by Females Who Have Been Assisted to the Colony.

Her Skirt Would Stand up Straight By Itself and Have to be Thawed Out.

His Wife Burst into Tears, Saying She Had Already Mortgaged Their Home so She Could Pay for Her Own Dredge Speculations.

An Irresistible Feeling of Solitude Overcame Me. There Was No Sound: Just a Depressing Silence.

Norman Conceded in His Mind that the Boomerang Would Crash Home Before He Could Snatch Out His Revolver.

The Sin of Cheapness: There Are Very Great Evils in Connection with the Dressmaking And Millinery Establishments.

The Poll Tax: One of the Most Mean, Most Paltry, and Most Scurvy Little Measures Ever Introduced.

Holy Wells: We are Order and Disorder.

After Some Debate, They Agreed That Killing the Priest Would Probably Bring Bad Luck.

God is Good and the Devil’s Not Bad Either, Thank God.

Notes

[1] Hodgson, The story about a pioneer family.

[2] Hearn, ‘Scots miners on the goldfields’, p. 81.

[3] Devine, The Scottish nation, a modern history, p. 337.

[4] Prebble, Culloden, p. 268.

[5] Clan/Family histories, n.d.

[6] Belich, Making peoples, p. 309.

[7] Patterson et al., Unpacking the kists, p. 3.

[8] Breathnach, ‘Recruiting Irish migrants for life’, p.40.

[9] Eldred-Grigg, Diggers, hatters & whores, p. 39.

[10] Hodgson, The story about a pioneer family.

[11] Life on the goldfields: Getting there.

[12] Hodgson, The story about a pioneer family.

[13] Hodgson, The story about a pioneer family.

[14] Mayne, ‘Goldrush landscapes: An ethnography’, p. 14; ‘Djadjawurrung’.

[15] Hodgson, The story about a pioneer family; Salmon, A history of goldmining in New Zealand, p. 22.

[16] Ballarat Star, 29 September 1860.

[17] Ballarat Star, 29 September 1860.

[18] Hearn, ‘The Irish on the Otago goldfields’, p. 77.

[19] Hodgson, The story about a pioneer family.

[20] Davy, Gold rush societies and migrant networks in the Tasman world, p. 67.

[21] Eldred-Grigg Diggers, hatters & whores, p. 87; Ballarat Star, 2 September 1861.

[22] Eldred-Grigg, Diggers, hatters & whores, p. 22.

[23] Salmon, A history of goldmining in New Zealand, p. 22.

[24] Bueltmann, Scottish ethnicity and the making of New Zealand society, p. 46.

[25] Devine, The Scottish clearances, p. 122.

[26] Simpson, The immigrants, p. 209.

References

Ballarat Star, 29 September 1860.

Belich, J. (1996). Making peoples: A history of the New Zealanders. The Penguin Press.

Breathnach, C. (2008). ‘Recruiting Irish migrants for life in New Zealand 1870-1875’. In Ireland, Australia and New Zealand: History, politics and culture. L.M. Geary & A.J. McCarthy (Eds.). Irish Academic Press, pp. 32-45.

Bueltmann, T. (2011). Scottish ethnicity and the making of New Zealand society, 1850-1930. Edinburgh University Press.

Clan/Family Histories. (n.d.). Clan family histories

Davy, D. (2021). Gold rush societies and migrant networks in the Tasman world. Edinburgh University Press.

Devine, T.M. (2012). The Scottish nation: A modern history. Penguin Books.

Devine, T.M. (2019). The Scottish clearances: A history of the dispossessed. Penguin Books.

‘Djadjawurrung’. (2022). Djadjawurrung

Eldred-Grigg, S. (2008). Diggers, hatters & whores: The story of the New Zealand gold rushes. Random House New Zealand.

Hearn, T. (2000). ‘The Irish on the Otago goldfields, 1861-71’. In A distant shore: Irish migration and New Zealand settlement. L. Fraser (Ed.). University of Otago Press, pp. 75-85.

Hearn, T. (2003). ‘Scots miners on the goldfields, 1861 to 1870’. In The heather and the fern: Scottish migration and New Zealand settlement. T. Brooking & J. Coleman (Eds.). University of Otago Press, pp. 67-85.

Hodgson, M. (n.d.). The story about a pioneer family. Privately published.

Life on the goldfields: Getting there. (2007). Life on the goldfields

Mayne, A. (2007). ‘Goldrush landscapes: An ethnography’. In Deeper leads: New approaches to Victorian goldfields history. K. Reeves & D. Nichols (Eds.). Ballarat Heritage Services, pp. 13-20.

Patterson, B., Brooking, T. & McAloon, J. with Lenihan, R. & Bueltmann, T. (2013). Unpacking the kists: The Scots in New Zealand. McGill-Queen’s University Press & Otago University Press.

Prebble, J. (1961/ 1996). Culloden. The Folio Society.

Salmon, J.H.M. (1963). A history of goldmining in New Zealand. Government Printer.

Thanks Bonnie and today I’m in Dunedin for a family do but also researching one of the most intriguing and feared characters in the town in the 1860s, James Grant. In his many published works he pushed the boundaries of libel as far as he could and even got horsewhipped for his pains, but the debate about what is and is not admissible in print still seems very relevant today. 😊

Amazing research Frank. And a well told story. It looks like there is plenty more to come!